‘Natives’ Land Act, 1913

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2019) ‘‘Natives’ Land Act, 1913′ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Land-Act/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

1. The broad context

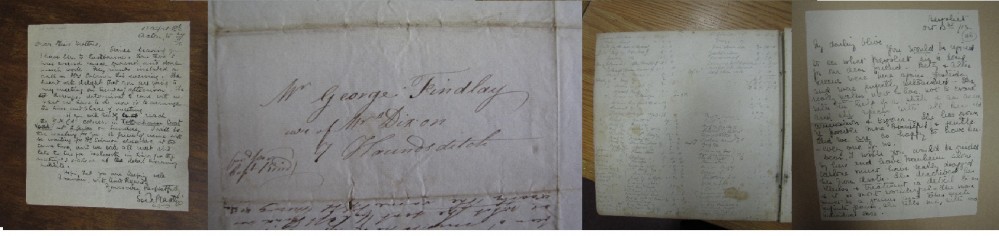

1.1 What is shown in the photograph above is the first page of a piece of legislation enacted in the South African parliament just three years after Union had occurred in 1910.

1.2 The ‘Natives Land Act’ was passed in June 1913 and is frequently described as the originating and definitional legislation in establishing the apparatus of segregation and apartheid and disappropriating South Africa’s black populations from land possession and ownership. It might be described as having mythological status in this regard, for, while not denying it had negative consequences, the in-depth historiography suggests something quite complex about the origins, content and effects of the Act. Equally or more consequential legislation had been passed earlier, the legislation itself came about because of different political purposes, its immediate effects were different in different places and in many were not as usually described, and its main negative effects occurred in the longer run and for other reasons.

1.3 Context is different from cause is different from intention is different from content is different from immediate effect is different from subsequent consequence. ‘Different’ here means that these are not coterminous, although of course they have connections.

1.4 To start at the beginning in teasing out what happened is quite difficult, because considerations of land and labour have been at the forefront of the settler presence in South Africa since the seventeenth century. For white people, land meant subsistence, livelihood and potentially wealth; labour meant that more land could be used for animals or crops; cheap labour meant that livelihood and wealth could be greater; constrained labour fettered to particular places meant compliance. Approaches which emphasise one or the other miss the point because, like horses and carriages, land and labour, labour and land, have each implied the other in this settler context.

1.5 In addition, from early on, ordinances were passed in both British colonies and Boer republics which legislated that people ‘out of place’ from a particular legitimated land-holding had to have passes which allowed them to be legitimately so, or otherwise legalised punishment would follow. These points about the evolution and enforcement of a pass system to regulate labour in and out of place need to be factored into the land and labour relationship.

1.6 ‘The beginning’ might be quite difficult to decide upon, then, but earlier consequential official Acts which came into existence well before 1913 are known about. A number of these could be mentioned; but albeit one point in a long line of successive official measures, the Glen Grey Act of 1894 still stands out. It was passed in the Cape Colony under the Premiership of Cecil John Rhodes, but was seen and intended to act as a template more widely across South Africa and in other settler colonies as well. It limited the land available to African peoples by demarcating locations in an area, specified the maximum amount of land that could be held, instituted a system of primogeniture, stopped mortgages, and inhibited if not entirely prevented land sales. The intention and effects were to create ‘native place’ and, when this was insufficient for its growing surplus population, to ensure that they entered a wage-labour market whilst still belonging to the ‘native place’.

1.7 The 1913 Land Act came about at the end of this long and largely gradual and piecemeal process, which had variations in different areas of the country. The Act recognised rather than caused dispossession as an ‘already in process’ matter in particular areas of what had become South Africa in 1910.

1.8 Also part of the wider context is that the different white populations and the politicians who represented them in what became the Union government in 1910 in many respects disagreed but, as debates in the Constitutional Convention that travelled the country and recommend the centralised rather than federated way that union would occur show, they agreed on a central matter. This was regarding ‘the natives’; and as Olive Schreiner put it, the white population wanted more and more and more because they embodied labour and labour was wealth; but this ‘more’ was in a context in which such things as the Bambatha Rebellion in Natal in 1908 must not occur again and could not occur anywhere else either. Union and the combination of the earlier separated settler states was the safeguard.

1.9 And what of these political and related differences? Again, many could be picked out, but the most salient for this discussion concerns disagreements between Transvaal and Free State politicians, which had occurred earlier regarding the conduct of the South African War and the peace treaty ending it, but also with regard to accepting or not the limited franchise accorded to property-owning black men in the Cape, working with or resenting and opposing the remaining shreds of British Imperial involvement in South Africa post-1910, and concerning the kind of legislation that should be passed in relation to white interests and specifically those of the Boer or Afrikaner population.

2. Pre-text

2.1 The wider circumstances also impacted on the particular factors which led to the Natives Land Bill being drafted, debated, then passed. They were filtered through political differences which became increasingly severe disagreements, with Feinberg (1993) having provided a detailed and substantiated account of how the political process developed.

2.2 Louis Botha was appointed as the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa. In spite of their differences and with some reluctance, he appointed Hertzog, a Free State political luminary, to the Union cabinet because his political importance was such that he could not be side-lined. In office as minister of justice, Hertzog promoted dual language teaching in schools and giving parity to Dutch and English in official contexts, and also opposed many policies connected with the rapprochement with Britain. Disagreements about these reached a head; Hertzog would not resign; Botha resigned the government but was asked to form another; he appointed a new cabinet excluding Hertzog.

2.3 Outside government, Hertzog and fellow Free Staters were as much irritants as earlier. Many in the Boer/Afrikaner population were dissatisfied politically with still being aligned with Britain, and many also wanted more stringent policies regarding African populations. As well as promoting such causes, Hertzog was beginning the process which would lead to the formation and break-away of the National Party, formed in 1914.

2.4 Johannes Wilhelmus [JW] Sauer was a very experienced long-term Cape politician and held ministerial appointments in both Botha governments. Latterly he was minister of agriculture and became a point of attention for the large Boer farming population and also the Free State – and increasingly nationalist – politicians. Sauer had announced at the beginning of the 1913 session that he would not be introducing legislation to regulate land or agricultural labour, but by March this was in the offing and the Natives Land Bill was soon being debated.

2.5 A number of factors seem to have been involved. Sauer, a man of established liberal principles, was targeted for political attention; the Free State contingent of elected politicians promoted the greater regulation of land with regards to ‘Native’ interests, partly as a means of getting at Sauer, partly to annoy Botha, partly to enhance their electoral powerbase. Many different interests were represented, with some agreement that land policies needed to be changed. However, although there were complaints about the speed at which the Bill was being pushed through, including from politicians who supported it, by July it had passed into law.

2.6 Sauer died following a major stroke at the end of the year. Olive Schreiner lamented that his last political act had been to introduce this retrograde legislation, although she had never given much credence to his liberal pronouncements anyway and thought that acts (in the everyday sense of the word) speak much louder than words.

3. The Act

3.1 The full text of the Natives Land Act 1913 can be accessed here.

3.2 This is a relatively short piece of legislation with most of its text taken up by specifying detailed inclusions and exclusions, with a relatively small amount of words given over to saying what the Act was for and would do. It defines ‘natives’ as ‘a member of an aboriginal race or tribe’; it sets up locations – ‘scheduled native areas’ – in which ‘native’ people are to reside; it limits the buying of native land by whites, and the buying of other land by Natives; and it establishes a commission to specify which other land was to become part of these locations, planned to be considerably extended.

3.3 In more detail, people were defined as ‘native’ were prohibited from purchasing land outside the demarcated ‘scheduled native areas’; a commission (the Beaumont Commission) was to demarcate these; and this would be linked at a national level to the system of reserves already established in some parts of the country. However, although the Beaumont Commission met and made recommendations, the large increase in location lands that had been anticipated when the Act was drafted never happened, although other aspects of the legislation remained in force.

3.4 It was the provisions in the Land Act concerning tenancy that took on most importance in the period after 1913, and it is these and their effects which have been described in mythologised terms, with the rather different findings of academic research largely not having made much of an impact on popular understandings. This point will be further considered under the heading of post-text.

4. Post-text

4.1 Considerably after the event, for most people what is now known about the 1913 land Act is, even though this may not be realised, filtered through the view contained in Solomon Plaatje’s famous book, Native Life in South Africa (1916). Plaatje describes the advent of the Act as sudden and cataclysmic, that ‘the South African native found himself, not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth… a great revolutionary change . . . wrought by a single stroke of the pen’ (pp.7-8). His account was based on detailed observation and interview-style conversations during a trip on bicycle around Kimberley and the Free State, and describes the desperate situation of African sharecroppers or bywoners in the Free State who had been ejected from farms.

4.2 In one of the first accounts to make detailed use of Plaatje’s work, Wilson commented that ‘few laws passed in South Africa can have been felt with such immediate harshness by so large a section of the population’ (1971, p.128). Many similar comments have followed. There has also been a strain of detailed historical enquiry which suggests that, while valid for the area he covered, Plaatje’s account may not ‘travel’ elsewhere, where circumstances were different.

4.3 Subsequent work, initiated by Keegan (1987; and see also references at the end for other interesting discussions) suggests modifications to this as a general statement. It is likely that a significant number of Free State farmers were primed to carry out concerted action in removing African sharecroppers/bywoners from their land, influenced by debates from local political leaders. Here the Land Act was not an originating cause, but a legal measure or tool that enabled them to carry out what they had wanted to do for some time but had been previously prevented from by custom and practice and the legal situation. It is clear, for example, that such summary ejections did not happen in other areas, where the pre-Act practice of shared land use continued for a considerable time, the eastern Transvaal being a case in point.

4.4 In addition, as well as generalising from a perhaps atypical area, an edge or perspective was perhaps given to Plaatje’s view because of his role within the Tswana-speaking Barolong elite in the northern Cape/Free State, including in respect of his patron Silas Thelesho Molema. These men were amongst the most important black owners of land in private tenure, and consequently the Act ended or at best undermined their legal right to purchase land on the private market and negatively impacted on their position as landlords.

4.5 A detailed investigation of all these factors by Beinart and Delius helpfully suggests that:

“the Act did not take land away from African people directly, and in the short term had a limited impact. Its most immediate effect was to undermine black tenants on white-owned land, but even here the consequences were mixed and slow to materialise. In many ways the Land Act of 1913 was a holding operation and a statement of intent about segregation on the land. These are some of the most difficult issues in understanding the Act and its legacy, in part because the Act itself tends to become subsumed into, and ascribed responsibility for, other historical processes: dispossession during the nineteenth century and apartheid in the second half of the twentieth century. Some recent commentators also underestimate the scale and character of African settlement on white owned farms at the time – an essential element in understanding the Act.” (Beinart & Delius 2014, p.668)

5. Legacies

5.1 it seems reasonable to conclude that in the short-run the Act had serious effects in some places, but more generally the picture was much more mixed and in some, perhaps even most, areas there was little short-term change. This does not mean that changes with respect to land occupation and possession were not occurring, but that these were much more locally specific, patchy and gradual.

5.2 In the medium-term, a raft of other measures were introduced promoting segregation and then apartheid. In this regard it has been proposed that:

“The Act laid the foundation for segregation and apartheid through most of the rest of the century: the homeland policies of Hendrik Verwoerd, the imposition of state-approved and appointed Bantu Authorities, the system of influx control and the hated ‘pass’ laws, and in the towns and cities, the Group Areas Act. Forced removals continued right up to the 1970s and 80s, as people in the so-called ‘black spots’ in the ‘white’ countryside clung to their land” (Hall 2014, p.1)

5.3 Hall states there are four longer-term legacies of the Land Act – rural poverty and inequality, urban poverty and inequality, division, alienation and ‘invisibility’, and dualistic governance. However, how these are separated out from wider political machinations and policies as things ’caused’ by the Land Act is not explained or evidenced. Perhaps the most pertinent of these claims relates to ‘dualistic governance’, because the Land Act in this respect built on provisions in the 1894 Glen Grey Act which created ‘natives’ in just such a dualistic way, as belonging to a rural ‘native space’ and subject to customary rule, and as urban displaced ‘native’ labour subject to white rule.

5.4 In the long run, i.e. now, the Act has become mythologised through being conflated with and becoming a covering term for all the other changes that had happened, as in the quotation above. And in turn, its resonance in this respect comes from a reliance on Plaatje’s account, such that discussions of the Land Act often start with a quotation from Plaatje’s book, used as the evidential basis for the argument that follows.

6. And what of whiteness?

6.1 The passing of the Land Act and the way in which its solidification of dualistic governance entered the national social structure of South Africa in 1913 is important in considering whiteness and its effects. Such dualistic provisions and practices were earlier present at local levels across the former colonies and republics, but in a more varied and happenstance way. The 1913 Act stands for the combination and unity, mixed with division and disagreement, of the white presence as enacted through the formal apparatus of white rule.

6.2 The separation that it solidified between, and the subsequent co-existence of, customary rule and formal political rule remains a presence even now. This is not only in South Africa but many other former colonies too, as Mamdani (1996) has powerfully argued.

Useful references

Beinart, W. and Delius, P., 2014. The historical context and legacy of the Natives Land Act of 1913. Journal of Southern African Studies, 40(4), pp.667-688.

Feinberg, H.M., 1993. The 1913 Natives Land Act in South Africa: Politics, race, and segregation in the early 20th century. International Journal of African Historical Studies, 26(1), pp.65-109.

Hall, R., 2014. The legacies of the Natives Land Act of 1913. Scriptura: International Journal of Bible, Religion and Theology in Southern Africa, 113(1), pp.1-13.

Keegan, TJ, 1987. Rural Transformations in Industrializing South Africa: The Southern Highveld to 1914 (Basingstoke, Macmillan,),

Mamdani, M 1996. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of late Colonialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996

Moguerane, K., 2016. Black landlords, their tenants, and the Natives Land Act of 1913. Journal of Southern African Studies, 42(2), pp.243-266.

Morrell, R., 1989. African land purchase and the 1913 Natives Land Act in the eastern Transvaal. South African Historical Journal, 21(1), pp.1-18.

Plaatje, ST 1916. Native Life in South Africa: Before and Since the European War and the Boer Rebellion London: P.S. King and Son; and Johannesburg, Ravan Press, 1982.

Walker, C., 2013. Commemorating or celebrating? Reflections on the centenary of the Natives Land Act of 1913. Social Dynamics, 39(2), pp.282-289.

Wickins, P.L., 1981. The Natives Land Act of 1913: A cautionary essay on simple explanations of complex change. South African Journal of Economics, 49(2), pp.65-89.

Willan, B. 2018. Sol Plaatje: A life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje 1876-1932 Jacana Media

Wilson F, 1971. ‘Farming, 1866–1966’ in L. Thompson and M. Wilson (eds), The Oxford History of South Africa Vol. 2 Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp.104–71.

Last updated: 11 January 2020