De/civilising processes: State-formation, habitus and ‘personality structures’ in thinking with Elias

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2017) ‘De/civilising processes’ http://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Thinking-with-Elias/Decivilising-processes/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

1. Introduction: Elias in South Africa?

1.1 Certainly the best-known aspect of Norbert Elias’s work concerns the ‘civilising process’, in particular through the second of his books to be written and the first to appear in English, The Civilising Process (1939 in German, 1967 in English, 2012 Collected Works edition). As well as bringing him still-increasing fame and arising position amongst social and sociological theorists, it has also brought with it some confusion concerning Elias’s thinking about this.

1.2 For some commentators, ‘civilising’ has been taken rather too literally and as though referring in a value-laden way to increasingly civilised (aka better) beliefs, manners and ways of behaving. This has been criticised as both naïve because this is not actually the state of the world, and relatedly as politically reprehensible because seen as valorising the rich white North. It seems that some of them have not actually read what he wrote! Also the idea of a civilising process has been seen as though he is suggesting a revamped Whig view of history, as inevitable progress. Again, this traduces what he actually wrote. The word ‘civilising’, then, has brought troubles as well as analytical strengths and possibilities, although it is clear that Elias intended neither of the ways of thinking about the civilising process just sketched. Rather, Elias is interested in what in societies in Europe has over time been perceived by them as ‘civilised’ and the direction in which manners and morals and such key matters as state-formation have proceeded. So his analytical attention is on changes in what is perceived as ‘civilising’ for people and groups of the past and the present, not ‘believing’ in this himself.

1.3 In addition, built into Elias’s way of thinking about societies and changes over time is the idea that a continual forwards and backwards movement constitutes ‘sociogenesis’ or the processes of change, for societies are always in media res, and these processes involve are ‘barbarising you’ as well as ‘civilising’. Rather than political or analytical naivete, Elias is well aware that the world of European societies is constituted by violence as well as pacification, penury as well as accumulation, barbarism as well as civility, and that the large-scale developments characterising the processes of change in these societies are always complex ones that are cross-cut by their ‘Others’.

1.4 As these comments indicate, Elias is concerned with the processes of change generally, with how change has been configured within a number of interrelated European societies, and in the book on which the present discussion focuses, in Germany, or rather among the Germans. Studies on the Germans (Elias 1989, 2013) examines change generally, while also focusing on Germany from before its unification, through the period of its imperial, Weimar and National Socialist state-formations, to the point immediately before the two Germanies re-unified at the end of the 1980s. The book has been described as an extended exposition of Elias’s ideas about habitus, although this term takes a different form from how readers of the Bourdieu version might expect. Also, the explicit point of Elias’s analysis is to think wider than the Germans and Germany alone. This makes it possible to use its ideas framework to think quite literally outside the box, including in considering the processes of change outwith Europe. and so exploring its utility or otherwise in understanding, in the case for later discussion here, the processes of change in South Africa.

1.5 It has been suggested that this is an illegitimate move, because the assumption has been made by some critics that Elias’s ideas are the product of and concerned exclusively with Europe, and that ‘the’ civilising process is in fact the European civilising process. However, this cannot be decided by fiat, with other uses and interrogations of his ideas being ruled out of court, but is instead a matter for detailed and thorough empirical investigation. It is an over-stated and under examined evaluation to make, reflecting more notions of political correctness with regard to matters of race and racism than a minded evaluation of Elias’s work. Relatedly, few countries in the world are sealed off from all others and for all time. In the case of South Africa, it is impossible to separate off its history from this being in part a history impacted by a European and colonial presence, and which has made a mark long-term regarding not only matters of state- formation and re-formation, but also such things as ratios of power, the relationship between established and outsider groups and so on, all of which are core concerns within an Eliasian framework.

1.6 With regard to investigating and understanding the processes of social change in South Africa over the period that the Whites Writing Whiteness project has been concerned with, the 1770s to the 1970s, the conclusion is that Elias’s ideas have considerable utility so long as these are used in a ‘thinking with’ Elias way, rather than an attempt to apply them is made. Thinking with Elias, what comes into sight is something distinctively South African and which adds up to a ‘racialising process’. This is discussed later in more detail, well what follows looks at the ways in which civilising and decivilising are interrogated in Elias’s work.

2. Studies on the Germans

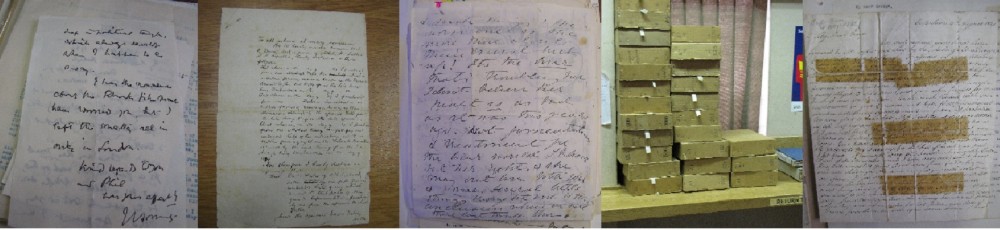

2.1 Elias’s (1989/2013) Studies on the Germans: Power struggles and the development of habitus in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which appears in his Collected Works as volume 11, is difficult to locate precisely in the temporal order in which his writing was accomplished and published because it is composed by pieces written at different points in time which have been stitched together. It was the last of his books to be published during his lifetime, and its production was actually overseen, not by Elias but by his editor, Michael Schroter. The Collected Works version has some importance differences from the version previously published in 1989 in German and in 1996 in English under the abbreviated title The Germans, because of important material helpfully added by editors Dunning and Mennell and also because some contents have been shifted around. In addition, some parts of the original have been either retranslated, or back-translated into German and then translated again.

2.2 The components of the ‘original book’ were structured somewhat awkwardly, which is why Dunning and Mennell reorganised content around a more chronological ordering of topics. These have produced a book of a different kind, which makes it clearer that Elias was writing about broad questions concerning social life, rather than focusing solely on Germany. That is, in this book he is using the German experience to raise not only particularities but also generalities about related developments elsewhere.

2.3 Elias writes (445; all page references refer to the Collected Works edition) that he realised that the breakdown of civilised behaviour and the rise of barbarianisation was important at the time that he started his work on the civilising process. This was originally commented on in a lengthy undated footnote (‘Civilisation and Informalisation’) and it is not clear exactly when he wrote it. However, it is interesting that he sees the decivilising aspect as a component of civilising processes from the start. Relatedly, he comments that it was necessary to distance himself from the immediate situation and not look only at short-term questions about the breakdown in civilising in the second quarter of the 20th century in Germany, but also to explore this over a much longer course of European development, and as part of changes in the civilising direction. In addition, he makes clear that he realises there are important differences between earlier attempts to wipe out whole populations and the attempted genocides of the 1930s and 40s. Earlier it was considered as conforming to a standard that people thought of as lying within normal conduct. Later it was different, with the moral standard prevailing in European societies generally meaning the terrible character of the deeds of the National Socialists was apparent.

2.4 In relation to National Socialism and the Nazis, Elias is in effect opposing extreme expressions of the view that genocide is endemic in societies and a hallmark of modernity, as provided by Bauman in particular (xxi). Specifically, Elias does not see people behaving in terms of morality or immorality, but instead sees moral codes as a product of the social order and with underlying processes like social conflicts, state formation, habitus changes and conscience formation being products of the interweaving of structures and processes (xxi- xxi). Studies on the Germans comes out of his attempts to make understandable the rise of National Socialism and therefore the things that followed from that, including World War 2, concentration camps and the post-war split of Germany into two states:

“Its core is an attempt to tease out developments in the German national habitus which made possible the decivilising spurt of the Hitler epoque, and to work out the connections between them and the long-term process of state formation in Germany. ” (3)

2.6 Once such matters are taken into social science consideration, “It then soon becomes evident that a people’s national habitus is not biologically fixed once and for all time: rather it is very closely connected with the particular processes state formation they have undergone.” (4).

2.7 As part of this, Elias also comments that, “The problem I set myself to examine was, then, to explain and make comprehensible the development of personality structures and especially of structures of conscience or self-control which represent a standard of humanness going far beyond that of antiquity, and which accordingly make people react to behaviour like that of the National Socialists (or similar behaviour by other people) with spontaneous repugnance.” (446). He relatedly comments that the personality structure of Germans had become attuned to absolutism and forms of superordination and subordination, command and obedience, in government positions and organisations, and also within the family and elsewhere (398).

2.8 Elias identifies some distinctive features of the German state-formation process that are of particular significance in understanding the German habitus and changes in this during the Hitler period. These are the fractured nature of the blocks of people who composed the Germans and issues with their sense of belonging together; difficulties in accepting Germany’s position in the hierarchy of states and the ways in which this changed; its state development process having more breaks and discontinuities than other states; and the role of the middle classes in its state formation being very different from elsewhere (4-20). He emphasises that linking the current social and national habitus of a nation to its history, and particularly to the state-formation processes that existed, is a (at the time of publication, novel) key to understanding the relationship between past and present (24). Regarding changes in 20th century Europe in general and Germany in particular, some structural aspects of change in society as a whole are picked out (26-35).

2.9 In the 20th century, the gross national product of most European countries increased at a rate almost unique, and which has been mainly used in improving living standards. This means that old problems can resurface, because people have a degree of physical security that is unprecedented, so these problems are characteristic of the later phase of industrialisation. However, a series of emancipatory movements has occurred over the 20th century and,

“These movements are about changing balances of power between established and outsider groups of the most diverse kinds. During the course of them the latter have become stronger, and the former weaker in power. These emancipating movements have, in one particular case, led to a reversal of the power-ratio in favour of the upwardly mobile outsider group… I am referring to the relationship of the middle class to the aristocracy…” (27)

2.10 The once superordinate established groups did not disappear. However, the power gradient between stronger and weaker groups decreased. A change in the power relations of many diverse groups brought feelings of uncertainty to those caught up in these changes, with conventional codes governing behaviour between such groups no longer corresponding to the actual relationships, and with this came problems of social identity and increasing status insecurity along with a shift in the search for identity. These changes also brought the decrease in power ratios between groups in society to people’s conscious attention, with accompanying spurts in informalisation in the relationship between such groups (35).

2.11 There are for Elias some main types of constraints to which people are exposed, from ‘animal nature’, from dependence on nonhuman circumstances such as weather, the constraints people exercise over the each other in ordinary social life, and self-control and self-constraints (36-39). Over the civilising process, the interplay between these changes over time, with self-constraints becoming more important. For the first time, people become widely aware of the shifts having occurred regarding former established groups and the increasing advantage of former outsider ones. As he phrases it,

“Put briefly, in the course of the civilising process the self-constraint apparatus becomes stronger relative to external constraints. In addition, it becomes more even and all-embracing… Social differences are certainly still fairly great, but in the course of the process of democratisation, the power differentials have lessened. Correspondingly, we have had to develop a relatively high degree of self-restraint in dealings with all people, including social subordinates.” (39)

2.12 Usually in sociology, social stratification is categorised in particular according to occupation and class. These are important, but for Elias they are not sufficient in themselves “to account for the actually observable ordering of people into higher or lower ranking strata.” (49). This requires knowing how members of society endowed with unequal power and status classify themselves and each other, because their perspectives are crucial in impacting their behaviour, how they behave as ‘we and they’. Doing this, it becomes apparent that, in Germany under the Kaiser, the actual ranking of different strata did not correspond to those in the highest occupation categories, and an important factor in actual social rankings was the idea of the ‘good society’. Elias sees “good societies as a specific type of social formation and as important in habitus”, because “They form everywhere as correlates of establishments that are capable of maintaining their monopoly position longer than a single generation, as circles of social acquaintance among people or families who belong to these establishments.” (54).

2.13 He also observes, “The increasing tendency to conceptualise processes as if they were unchanging objects represents a more widespread pattern of conceptual development running conversely to that of society at large, the developments and dynamics of which have noticeably quickened from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries” (134). Relatedly, a general shift from humanist moral ideas to nationalist ones emphasising country and nation can be observed in middle classes in most European countries over the period the 18th to the 20th centuries. And an idealised image of the nation became central to the self-image and scale of values. In Europe generally, nationalism meant emotional satisfaction was derived from looking back, with the core of self-image wrapped up in national tradition and heritage (148).

2.14 It was in connection with this change of emphasis from the future to the past and the present, and from universal to national characteristics and traditions, that concepts such as civilisation and culture changed from indicating processes and progressive developments, to referring to unchanging states of being. Overall, they served increasingly as symbols of the we-image of groups in the national order trying to find pride in past achievements and traditions (149).

2.15 Identity feelings changed in European states with the transition from ruling elites from the aristocratic classes to the middle classes, and with identification with their own compatriots becoming stronger, and those with people in other countries weaker. The result was that the we-and-they-feelings of identification and exclusion became more inward looking (157-8).

“When power politics came to be pursued in the name of a nation, certain basic aspects of the figuration that states formed with each other remained unaltered… But power politics, pursued in the name of the nation and not a prince, could no longer be conceived and represented as the policy of or for a person. They were politics in the name of the collectivity which was so large that the majority of its members did not and could not know each other.” (159)

2.16 Elias proposes that nationalism is distinguished from other major social beliefs like conservatism, communism, liberalism and socialism, which gain their primary impetus from the changing balance of power within a particular state and society. Nationalism is different because gaining its main impetus from the changing balance of power between different states (168).

2.17 This in turn shifts emotional bonds, which became to a much higher degree symbolic attachments, as the symbols of the collectivity (159). The way that this impacts on the formation of beliefs results in personality dispositions, in which many of those who are members are inclined to fight and if necessary die in the interests of the collectivity, with such feeling encouraged and it “releases symbols”. At the same time, such bonds work automatically to an extent and can be only partly modified in a direct way (172). Also, the double-edged character of such social norms is that they bind people to each other, and at the same time turn these people against others (174).

2.18 Another factor which Elias sees as important is that, while the general direction of this development was the same across industrialising states, the time at which these independent states within the European power-balance figuration entered particular phases differed a great deal: “The figuration was formed by societies at different stages of development, the less developed, less civilised and less humanised drawing the more developed towards their own level and vice versa.” (182). He concludes on this that it is not possible to understand the development and structure of inter-state relations by focusing on one of the compound states on their own – “one can understand it only as a figurational level sui generis, interdependent with others but not reducible to them.” (183).

2.19 Civilisation is never completed and always in danger because ensuring standards of behaviour and feeling depends on particular social conditions. These include self-discipline, which is itself linked to specific social structures, maintaining the supply of goods and standard of living, and solving intra-state conflicts, social pacification, and internal pacification too is also at issue (186).

2.20 These are key aspects of a civilising process, around the tension between pacification and violence. Elias discusses this with special reference to Germany, but at the same time also pointing out their wider relevance and applicability.

2.201 The idea of the biography of a state society, specifically Germany, is an interesting one and it would need to cover how Germany’s earlier feelings of weakness and power inferiority changed into the opposite when it became unified in the context of a victorious war in 1870 (192). More generally, understanding the development of Germany and current (1980s) ideas about force in the Federal Republic have to keep in mind developments in Germany’s position in the inter-state framework and so in the hierarchy of states: “The development of Germany shows particularly clearly how processes within and between states are indissolubly interwoven.” (193).

2.22 The desire for communication was achieved through victorious wars under military leadership, with the sense following that that war and violence were good political instruments on the part of many sections of the German population (195-200). Subsequent wars were approached by young Germans with the idea that involvement was wonderful and glorious. The conditions under which civilised forms of behaviour began to dissolve involved a process of brutalisation and dehumanisation. After both the First and the Second World Wars, younger generations searched for a more meaningful life and found what was produced by their elders was restricted or blocked, and there were feelings of being trapped in something that was rejected. For many of the young, the practical work of political parties was part of the problem, not an answer, as these embodied various of the weaknesses and shortcomings of existing society. In the context of (1960s) terrorism in West Germany, violence engendered counter-violence on both sides, and the power relations involved concerning the violence-potential of the state and also that of extra-parliamentary movements and, both in the 1930s and in the postwar context, also of 1960s terrorists. Similarly as in the Weimar period, some embittered young middle-class people drew the conclusion that social structure had to be changed through extreme acts, including systematic terrorist action.

2.23 On this, he interestingly states,

“Furthermore, especially in the Federal Republic, the difference between the moral ideas of the older and the ethos of the younger generations is particularly striking. As a reaction to the traumatic memory of the inhumanity of the Hitler period, a very accentuated ethos of standing up against inequality, oppression and exploitation and war and for a new type of decency between humans has become accepted among younger people… one can assume with some certainty that the problem of meaning for the younger generations, which was expressed in the terrorist movement among others, will make itself felt again and again, even in acts of violence, as long as people do not strive for improvement much more conscientiously and intensively…. ” (222)

2.24 How far the process of de/civilising will go and how it will shape a country depends on

particular cases and Elias comments that,

“It can vary according to the structure of authority, to the extent and form of internal conflicts, to the belief and behaviour traditions, to the division of power present and past, and to many other factors. Whatever they are, it is never a country’s immediate condition alone that accounts for the strength and nature of national sentiments and for the degree of barbarity of which nation is capable in its relations with those whom its members regard as enemies… the past leaves its imprint on the present order and conduct of people… The past, present and future operate together. Experienced situations are, as it were, three-dimensional.” (280).

3. Some theoretical pointers

3.1 Studies on the Germans is a large book with weighty content and there are more analytic concerns covered in it than are dealt with here. In particular, there is more in it with regard to Germany and the origins and growth of nationalism and the formation of National Socialism, as well as concerning the period after World War 2. There is significant discussion of the increase in informalisation over time as part of civilising processes (26-35), codes of honour and the German upper classes during the period of unification (49-98), comparison of this with the moral code of its middle classes, and comparisons with elsewhere. It also looks in detail at National Socialism and the breakdown of civilisation under the Nazis (223-316), and 1960s terrorism in the Federal Republic of Germany, which latter Elias treats as in large part conflict between the generations, where disaffected younger generations see violence as justified in the face of state violence (331-425).

3.2 For Elias, there are long-term shared developmental processes marking the intertwined sociogenesis that occurred in the European countries of his concern, specifically Germany, France and Britain. These include accumulation and the distribution of resources to their populations, the control of violence and the monopolisation of force by the state, and state- formation itself.

3.3 The past continues to impact on the present and its residues continue to circulate, and in this sense it also impacts on the future to come. At the same time, this is not a determined or fixed process, including because there can be major significant changes in state-formation, different states can manage accumulation, pacification and the monopolisation of force in different ways, and also the relationships between insider and established groups can change in unpredicted ways. But as discussed earlier, overall there is a general direction of developmental changes along which the European societies Elias discusses have moved in intertwined ways. Is this so in South Africa, are the directions different and if so in what ways?

3.4 Civilising and decivilising processes occur together. As part of sociogenesis, there are always backwards and forwards movements in what are perceived as civilising processes in any given society. This was part of Elias’s thinking from his first writings on, although earlier in his career he tended to focus more on forwards movements and developments and bracketed the more decivilising aspects also present. However, Studies on the Germans reverses this emphasis, and it demonstrates that decivilising is built into the very fabric of civilising processes.

3.5 Studies on the Germans also shows how in the context of German over time development, social structures, social processes and psychosocial aspects are intertwined with each other. In particular, Elias’s analysis explores the ways in which what he refers to as ‘personality structures’ are shaped and impacted by social structural formations, with his key example being the duel and how its role both changed over time and also remained central to prevailing notions of hierarchy, power, masculinity and superordination.

3.6 No country is an island and its processes of development and change in the last result cannot be analysed in isolation from its changing relationships with other state-formations. This is particularly so with regard to nationalism, which is always linked with the position of a nation-state in relation to others and the sentiments engendered around this. But of course it also applies more generally, for most state-formations are contiguous to or surrounded by other state-formations, and necessarily have to take into political account the prevailing and changing pattern of intra-state relations. In addition, some state-formations are internally fractured, and create ‘Others within’ so that something like quasi-state considerations have to be dealt with.

3.7 There is a change over time in the relationships between and relative positions of the established and former outsider groups in a given society or country, with the prevailing ideas of what is a ‘good society’ closely involved in marking out the established. Studies on the Germans raises the issue of whether and to what extent particular examples of those groups deemed to be ‘good’ can be used as proxy measures of ratios of power in the relationships between the established and outsiders. Elias’s analysis of duelling and the German honour code is insightful, but it also raises methodological and analytical issues and in particular because it proceeds from the perspective of the established, in the sense that it takes one of its valorised activities as the point of analysis whereas, for instance, selecting an ‘outsider’ political club or religious group might have lent a very different flavour to the discussion.

3.8 As well as insider and established relations, and those existing between one state- formation and others, in the context of 1960s terrorism in Germany Elias discusses relations and conflicts between the generations. In the particular historical circumstances prevailing, and given the history of relations between the generations in Germany in earlier times, his focus is on the gulf between the generations, with younger generations seeing the older as morally and politically wanting, and its control of political and other institutions as inhibiting or preventing their participation. In addition and importantly, the perception was of the state using force and violence in ways that legitimated using force and violence against it.

4. South Africa and its civilising process

State formation

4.1 Some features of the South African civilising process have followed the major structural aspects of state-formation in the European context, with regards to accumulation, pacification and monopolisation. But state-formation always exists in a complicated relationship with the population, those who compose ‘the nation ‘. Its complications are greatly increased in the South African context when looked at over the longue duree. From the outset of the European-dominated state-formation process, the white presence and its political leaders looked to European ideas, and ideals, about state formation, systems of governance, and also ways in which the state, social structures, manners and morals were interrelated. With accompanying moral codes and ideas, these have tended to the production of a particular kind of personality structure, around whiteness being between European and African, beleaguered politically, and with a heritage including an exaggerated style of masculinity, and the devolution of legitimated force and violence at a local and individual level.

4.2 Before the colonial period, local states certainly existed in southern Africa, but in ways differently configured from the emerging court/monarchical and imperial forms of Europe. These were then not so much succeeded by, as largely obliterated by, emergent European- style systems of governance (primarily the Boer republics of the Transvaal and Free State and the British colonies of Natal and the Cape) linked to strong local white territorial claims, with only their residues remaining in the form of ‘customary law’. These earlier settler states were then overwritten by the 1910 Union of South Africa, preceded by ‘adjustments’ of some borders so that some formerly linked areas were excluded and others included. Then the ‘apartheid state’ after 1949 had a number of distinctive features, one of which was a kind of supra-bureaucratisation, in which the state established governmental priorities and structures that were configured to pursue absolute control over the majority parts of the population.

4.3 This approximately 200 year period, from the arrival of relatively large contingents of European migrants through to the later 1970s and the increase of ruptures and fractures opposing the National Party one-party state by the African majority, has been the focus of WWW research. The distinctive features that Elias identifies regarding German state-formation are helpful in thinking about this, for they focus on the fractured nature of the blocks of people composing the population, difficulties in accepting the position of the state in the wider hierarchy of states, a discontinuous process of state development, and the different roles of superordinate groups in state formation. Although they take a particular form in the South African context, they can nonetheless be discerned as features of its state-formation process.

4.4 The 1994 democratic transition was preceded by a short period in which a number of these aspects of control were partially dismantled or sometimes overturned. During the initial period of transition, the nation-state was reconfigured in ways that supported a more federal system in which major provinces had increased governmental powers. However, there has been relatively little change in relationships between the established and outsider groups, with the exception of the creation of a large African political and managerial elite occupying key positions in politics, government, interstatals and major corporations. This has occurred alongside of an increased role for multinationals and large corporations within the framework of a neo-liberal style of government, and has also been associated with an increased hierarchicalisation in the relationship between elite groups and the majority of the population.

4.5 This brings into view the question of not only what is the state, but also when is the state and at what particular temporal junctures does it significantly change or become out of sync with what is happening to comparative states elsewhere? For instance, the form that the Union of South Africa took in 1910 was closely related to the emergent relationship between South African politicians and the British imperial government in London and how the latter saw its relationship with its dominions. In the 1960s, Macmillan’s ‘winds of change’ speech made in South Africa and in a year in which many African states achieved independence demonstrated the dislocation between its political zeitgeist and that prevailing elsewhere on the African continent and indeed among the ex-imperial powers. And in 1994, the year of political transition in South Africa, the winds of change were very different and its transformation became bound up with neo-liberal economic and political agendas which continue to mark its national life 20 years on.

4.6 Which component of the population and at what point in time, and what incarnation of local or national states should be taken as the focus? Clearly, all of the variations need to be included in an account of how and why South Africa’s developmental process occurred in the ways that it did and what the key residues of the past circulating in the present and likely to impact on its future are. Clearly too, present troubles in South African political and economic life can in part be traced to the partial nature of the 1990s political transition in which African elites superseded white ones, and in part to the development of a more ‘Africanised’ style of single-party government, with both involving the recirculation of residues of the past in the present.

The established and outsiders

4.7 From the establishment of the four settler states on, state-formation was a key activity and aim of the white-controlled system of politics and governance. While all state-formations dispose of accumulation, pacification and monopolisation unequally regarding different sections of the population, from the 1850s on this has been particularly marked in South Africa. It achieved a kind of apotheosis with successive National Party governments between 1949 and 1994, which systematically discriminated in every aspect of national life between different populations on the basis of assumed characteristics of skin colour.

4.8 What has occurred subsequently, slowly from the early 1980s and then more dramatically from 1994 on, has been a marked change in the composition of, as well as relationship between, the established and outsider groups. However, these relationships were very differently configured during the period between the first arrival of Europeans and the significant control of territory and the monopolisation of pacification and force by the European-style states in the Transvaal or South African Republic, the Orange Free State, Natal, and the Cape Colony, in approximately the 1880s and 90s. And even then there was a large active African intelligentsia and bourgeoisie, mission-educated and active in campaigning for equal rights, which was only subsequently repressed and with even the memory of this earlier time of possibility and hope made one of abeyance.

4.9 However, in the earliest period of the white presence, there was due appreciation on the part of travellers, military personnel, missionaries, traders and others that the balance of power, and through this access to knowledge, faith, goods, land and other desirables, lay in the hands and the force of the African majority. Knowledge about this is often occluded by the style of analysis of present-day secondary scholarship, often influenced by fictional accounts or one-off pieces of writing and extrapolating from these to a general picture. But the general picture as shown by the detailed historical record is more complicated, more diverse, and harder to comprehend the import of. What happened to change this earlier configurations of the African established and white outsiders, where it happened, and with what reverberations, is the $64,000 question, and addressing it requires the attention to the historical context, groups of people and their inter-relationships, that Elias insists is the requirement for understanding such developmental processes and the intertwining of their civilising and decivilising aspects.

4.10 In the case of Germany, Elias takes the duel and the moral and martial code of honour that surrounded and supported this as a proxy for the structural features of the relationship between the established and outsider groups. This ties understanding the configuration of super- and subordination in Germany to the activities of a ‘good society’ and thus to the concerns and organisation of the established, the superordinate group. Certainly he touches on aspects of codes and aspirations of those positioned as outsiders, including in relation to Romantic literary and cultural ideas and associated political aspirations. But the focus remains on the powerful.

4.11 How might these ideas about a ‘good society’ which acts as a proxy for understanding the structures of relationships between the established and processes of state-formation, and established and outsider groups in Europe, pan out in thinking about South Africa?

The commando as a ‘good society’

4.12 There is a duelling parallel in the shape of the commando system. The commando was a local defensive and offensive fighting group composed by call up in times of need, and consisting of all males over a particular age, usually around 12 upwards. This acted to defend life and property against attack from African forces usually protesting over the abrogation of land or objecting to the white presence as such, and also as an offensive group in attacking African peoples perceived as a threat, and in carrying out slaving raids further north in southern Africa for, usually, young children who would act as life-long servants. In many areas, the commando was composed by Boer farmers and their sons, but where people from other white ethnic backgrounds lived in an area under the aegis of one of the Republics, they too were liable for commando service. In addition, the commando was linked to the ‘heemraden’ organisation of local governance, in which men (always men) were appointed or elected to roles involving the administration of justice, in particular with regards to contracts, land and other legal matters.

4.13 The commando system gave rise to great intra-group cohesion, a clear and enforced hierarchy and system of control both over outsider groups and also other members of the established ones, and the local near-monopolisation of force. The commando system also produced ‘men’ and an exaggerated form of masculinity, as with the honour and duelling system in Germany.

4.14 Elias warns against thinking of the present and the future as though in a simple sense ’caused’ by factors A or B in the past. At every point in time, he counsels, there were always other possible outcomes, not a simple lineage of causes and outcomes, and so analytically the move must be to work forward in time and explore all the possibilities at any one point and why and how things eventuated as they did, but also why other things did not. However, his emphasis on the ‘good society’ and the system of duelling in Germany has not been treated in quite this way, but more as a kind of fixture conjoining social structure and social processes. The commando system offers an interesting comparison.

4.15 Certainly the commando system was a dominating presence for a long period of time, but it was also one which was locally and frequently neither fully enforced nor fully operative. It acted as it did for white people, white men specifically, and Boer men in particular although not exclusively. Then with the processes of development and especially urbanisation among the white population, it eventually lost its force, although its reverberations continued, and still continue, in a number of ways regarding the association between men, masculinities, guns and group and individual force and violence.

4.16 The commando system was a sectional figuration, even during its heyday in the period up to approximately the early 1920s and increasing urbanization. Its apotheosis was the South African War 1899 to 1902, while the 1914 Boer Rebellion defeated by a government under Afrikaner control signalled its slow demise. Its sectional interests mapped onto fractures even among the white communities, distinguishing Boers from urbanised educated Afrikaners, as well as from whites from other ethnic groups, and mainly though not exclusively operating in the old Boer Republics of the Transvaal and Free State.

Conflict and the generations

4.17 The initial ‘state capture’ in South Africa involved the Randlords, the financiers and mine owners who controlled first its diamond and then its gold and other mineral production. This was followed by the large support in the form of policy measures and also finance given by the state to develop Afrikaner capitalism as a counter commanding heights the economy. The highly controlled bureaucratic state post-1949 that is associated with the institutionalisation of apartheid policies was in fact a development rather than a departure from earlier state processes in South Africa. In this sense, the present ‘Africanisation’ of South African political structures – including Zuma, the ANC and corruption; state capture and the role of the Guptas – can also be seen as a development rather than a rupture or departure.

4.18 The ANC developed a well-organised ‘command and participant’ organisational structure that during the struggle period also involved a high degree of secrecy and acquiescence in decisions made elsewhere in the command structure and also established a central group of men with overall control and responsibility for key aspects of the organisation. While many of the personnel involved then have died or retired and been replaced by younger cadres, aspects of the structure and system of control and command remains in place. Added to this, the ANC has won overwhelming success in local, metropolitan and national elections and has held power in many areas of the country consistently since 1994. Although opposition from other political groupings can be considered par for the course, there has been increasing internal dissatisfaction, loss of membership, and in recent times violence expended in expressions of considerable anger as well as dissatisfaction with political performance.

4.19 The bottom-line seems to be that South Africa has not magically ‘transformed’, that reform has been considerably slower than anticipated, and that some people within the ANC have taken to corruption in a major way. Earlier anticipations of change seem to have given way for many people in the post-Marikana massacre era to the feeling that it is legitimate to engage in anti-state violence. And while by no means all of this upsurge is associated with a disjuncture between expectations and rewards that divides older and younger generations, certainly some of it is, with the rise of the Economic Freedom Fighters and the RhodesMustFall and FeesMustFall campaigns indicate.

Whiteness: a ‘personality structure’?

4.20 Historically, the commando system was important in South Africa and provided a base- line social structure and organisation within which a large proportion of white males were incorporated. It had strong figurational characteristics persisting over numbers of generations, and also considerable symbolic import. But like Elias’s focus on dueling with its code of honour and figurational societies of men, the female half of the white population was associated only at remove and in relatively distanced ways, although this was less so compared with Germany. But such a focus begs two questions. One is, where were the women and what happens if women’s position is taken as seriously in an analytical sense to that of men? The second question is, what were the ‘good societies’ for different groupings within the African majority and how were these have changed because of the incursions of colonial, Republican and Union rule?

4.21 Regarding the position of white women, their place in the social imaginary of white South Africa has been much evoked. In the settler society, for many if not all, whiteness was equated with separation from the ‘other’, living life in an enclave or enclosure, and when outside of it protected by circling wagons in a defensive laager, with the latter perhaps now in a transformed version existing in the more exclusive and completely enclosed shopping malls in South Africa. The title of an early novel by JM Coetzee – Waiting for the Barbarians – is indicative here. So too have been the successive moral panics in different parts of southern Africa referred to as ‘the black peril’, with earlier manifestations focusing around claimed widespread sexual and other violence towards white women, and later incarnations concerning farm invasions and murders. In reality, however, the peril has been experienced primarily by black people, with such panics used to justify extreme measures.

4.22 Responding to the second question, of what ‘good society’ existed for the African majority, contenders here will include the churches, political organisations including but not confined to the ANC, and in particular four young men activities around the armed struggle. As well as their independent existence, shadow versions of these also come within the remit of whiteness and ‘personality structures’ because contributing to prevailing ideas about the black peril.

4.23 There is of course more to be said about the South African racialising process than this. A development of this analysis appears in a separate essay ‘ thinking with Elias’ essay, and is also the subject of a book based on WWW research:

Liz Stanley (2017) The Racialising Process: Whites Writing Whiteness in Letters, South Africa 1770s-1970s Edinburgh: X Press. Go to https://www.amazon.co.uk/Racialising-Process-Writing-Whiteness-1770s-1970s/dp/1521403643/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1498211823&sr=8-1&keywords=racialising+process

5. In brief conclusion

5.1 Studies on the Germans is a rich examination of the processes of civilising and decivilising with particular reference to the Germans, but it also how’s much wider relevance. It is extremely useful to think with; and like all thought-provoking books, it raises as many questions as it provides answers. Many of its ideas and conceptual terms need modification when thinking about South African context – but then, they would regarding other European contexts as well, as indeed Elias himself emphasises in the book. Overall, its conceptual armoury is extremely helpful while also requiring modification and extension because, as Elias would have been the first to recognise, there are things that are specific to the history and location of South Africa and getting to grips with these requires tailored terms of reference and means of investigation.

5.2 The changing configurations of relationships between the established and outside groups and changing ratios of power signalling such relationships seem to be key in the complex developmental aspects of the South African civilising process. They give insights into the forms that sociogenesis took at different times and places over the 200 year period from 1770s to the 1970s, and indeed beyond the 1970s.

Last updated: 13 May 2021