Analysing the Racialising Process

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2018) ‘Analysing the Racialising Process’ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Thinking-With-Elias/Analysing-the-Racialising-Process and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

1. Ex Africa Semper Aliquid Novi – From Africa Always Something New

1.1 ‘Thinking with Elias’ needs to encompass the fundamentals, in particular regarding the sociogenesis of society, that is, the continual ‘becoming’ of the social order and its constant processes of change. What is proposed here is that, contra Elias’s ideas about the civilising process, a Europe-located theorisation of the processes of change over time, the evidence provided by the WWW letters conveys that a distinctive racialising process has marked South Africa’s pattern of sociogenetic change.

1.2 Elias’s gaze was largely upon European societies, Germany, France and Britain specifically. At the same time, he recognises that particular times, particular circumstances and particular sets of people seriously. Repeatedly, his approach points up the importance of the relationship between the micro level (including such things as etiquette manuals, the use of forks and the arrangement of rooms), and the macro level (including ruling courts and the character of the state), recognising the interconnectedness of all aspects and levels of sociogenesis. The result is that his framework of ideas – with appropriate bending and rebuilding – can be used to think outside the European context, and to do so in a way that rejects thinking in binary micro/macro ways about ‘levels’ of the social order.

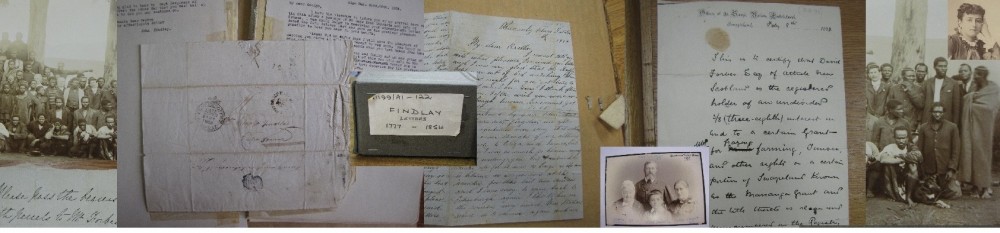

1.3 Letters register and index change in the representational and heterotopic ‘world’ that the letters of white people writing about whiteness comprise; and they conjoin recording the minutiae of the quotidian and everyday and observations on broad trends, public events and social structures. In the WWW research context, they have been conceptualised and analysed regarding the long-term character of emergent social change in South Africa over the 200 years from 1770s to the 1970s. Might South Africa have had a civilising process similar to what has been described in the European context? Or is perhaps should it be seen in terms of Africa and with a separate African process occurring? Or is there something specific about South Africa that means a distinctive process of change, different from both European societies and from others in Africa, can be seen at work there?

1.4 The history of South Africa certainly did not start with the arrival and development of the European presence, and in many ways the form its state has taken and is presently taking, its social organisation, its economy and its peoples, are all also of Africa. At the same time, the continuing impact of its European-influenced aspects have made a difference in a range of ways, as have the associated impacts of imperialism and capitalism as well as colonialism and how they have played out over time. These are entangled histories with effects all round, regarding how the resources, products and people of African and other colonies have changed the European metropoles as well as vice versa. These entanglements have included the presence of white populations of settler colonial origins, in South Africa’s case with its white population having abrogated and retained a vast reservoir of power and resources, achieved in large part through the suppression, exploitation and oppression of its black majority. They have also included its would-be close relationships with European and US world powers. South Africa as a national state from 1910 on certainly had, and for a long period of time continued to have, a close eye on potential allies outside of its borders, but less on other African states and more on European ones.

1.5 Seeing South Africa in solely African terms would need to bracket the effects of its specific history, which includes the impacts and remaining reverberations of colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, and its racial order and its formerly white-controlled state apparatus. Here the letters of white people in South Africa written over the 200 years from the 1770s to the 1970s re-enter the frame, in witnessing and representing the force and impact of its particular history and doing so in thought-provoking ways. These letters are not only responsive to change, they also represent change and in many respects embody their writers and their addressees engaging with such changes.

1.6 The letters of white people writing whiteness provide a point of ingress into the unfolding everyday processes of change occurring, and among other things lend themselves to thinking about transitions over time in South Africa. The details of what their contents and their form or structure add up to are considered in the ‘theorising letters’ pages on the WWW website, including what they tell regarding the formation of colonial states, the creation of labour and the conduct of work ‘per Kaffir’, their expressions of racial categorisations, the performative aspects of letters, the ways in which ideas about civility are represented, and silences and absences from their content, among other matters.

1.7 And as this list indicates, as well as representing the everyday, these letters also point provide a point of ingress ‘from below’ into the processes of state formation, monopolisation of legitimate force, violence, changing ratios of power around the positions of established and outsider groups, understandings of habitus and good societies to belong to, and how the ‘We-I’ relationship is lived out. In doing so, they show a distinctive trajectory for South Africa that makes it significantly different from European experiences of long-term development. Regulation, categorisation and racialising are central in this and the racialising process at work is focused on in what follows.

2. The Racial Order & Racial Categorisation

2.1 Many factors are involved in producing social change in a society and these are complexly interconnected. Consequently beginning with one factor rather than another can give a misleading impression that this is ‘the start’ and what sets it all in motion, rather than being just a convenient way to commence. In avoiding this problem, discussion here begins with comments on the racial order and on racial categorisation in this from two keen observers of South Africa. The observations about race and society come from political mastermind – and white – Jan Smuts, often known as ‘slim Jannie’, meaning wily; and the comments about racial categorisation are from sociologist and educator – and ‘coloured’ – Neville Alexander.

‘The indispensable native’: reality for Smuts

2.1 Jan Smuts wrote some hundreds of letters to May Hobbs, discussed in detail elsewhere. His comments about race matters in them are few and expressed in a low-key way, but they nonetheless provide a succinct overview of how he saw South Africa’s racial order and his ‘as it naturally is’ assumptions:

“… This is a good country – lazy, easy-going, pleasant to live in, with the indispensable native to do all the hard work, and with a Nature around such as is probably nowhere else to be found.” (28 April 1927)

“I have come back here into a sea of political troubles. General Hertzog is still busy with his Native problem, but like many other looks to me for finding the solution. …” (26 Feb 1930)

“… a huge buffalo just killed by lions… we found the natives grinning with pleasure as they divided the carcass and thought of the joys of overfeeding. …” (27 July 1932)

“Peter [Hobbs’ son] killed two elephants… I never like killing – even of game, unless it be birds for the pot. But Peter has to protect his natives and had no choice.” (7 Jan 1935)

“… our principal trouble out here is colour questions – straightening out questions between black and white and coloured in this piebald country. In addition, we have always a tangled Indian problem with us… Colour here is what Fascism is in Europe – the form the Devil assumes on this continent…” (5 March 1939)

“I am glad that Peter is now among the Europeans. People who live too long among natives tend to develop a native mentality!” (15 May 1939).

(Hobbs Collection, NAD Pretoria)

2.2 In Smuts’s comments, made as observations of ’real reality’ and ‘the facts’ rather than as claims or just one viewpoint among others, the racial order is seen to be at basis a categorical one. This is the sense he conveys of a category-order that positions people – white, black and coloured – in relation to each other. ‘Native’ used as a category here has particular characteristics associated with it which are seen as definitional. It is fundamental to his view of the racial order, as is ‘white’ as a category-pair and seen to have very different, diametrically-opposed attributes.

2.3 Without ‘natives’, the political problem Smuts perceives would not exist and only he can solve the problem. The ‘proper’ relationship between the two category-types as he views it is separation, although this has to be achieved in South Africa within a system in which white has responsibility for and over black, one of the two principal groups defined as ‘natives’. And while ‘natives’ do all the hard work, the only specific examples Smuts mentions involve scavenging and other state of nature activities. This is account of South Africa as a society based on ideas about ‘natural order’ and fixed attributes assigned to people on the basis of skin colour categorisations, seeing such things as intractable and indeed immutable.

Regulation & categorisation

2.4 Neville Alexander’s (2013) observations are that racial categorisation and the ongoing processes of racialising are not only still present in South African society two decades after the democratic transition (and even longer after Smuts’s letters and his time as a political leader of the white-controlled state), but even more omnipresent when he wrote, some 20 years after black majority government, than earlier. Indeed, they have now reached down into ever more detailed aspects of the everyday. One of many examples discussed concerns Alexander reporting to the police he had witnessed a traffic accident, being told that this required him to locate himself in racial categorisation terms, and his refusal meaning that his witness statement was not taken. He relatedly points out that the requirement of racial categorisation as an everyday way of placing things, people and events is both completely ritualistic (it is collected as a requirement, but is not used), and has become ever more present in the wider re-invention of race as a dominating feature of social life, rather than the ‘rainbow nation’ dissolution celebrated in the 1994-transition having occurred.

2.5 With allowance made for changing ‘descriptive’ terminology and a revision of the moral evaluations involved, now – some 80 years after Smuts’s letters were written and 60 years after his death – his idea of the racial order is surprisingly still present. It is not entirely intact in the sense that there have been no changes, but it remains present in the sense that its ‘natural order’ view is a continuing materiality in terms of how many people and organisations understand society. In some respects the racial order in South Africa has of course changed, with moral evaluations having shifted or even been reversed and the relationship between its established and outsider groups moderated. However, some features have become exaggerated more far-reaching and more widely applied. The racial order now is less stark and less imbued with negative moral assessment directed towards ‘them’, and more trivial and more concerned with the quotidian and how things are seen to be. And it is bound up in and reinforced by regulation and categorisation at governmental, institutional and organisational levels.

Considering the state & regulation

2.6 Whenever the question of whether and how societies change is considered, the role of the state needs to be taken account of. This is not to assume that the state is necessarily the source or the focus of change, simply to recognise that state organisation and its apparatus has developed along with the populations of countries growing and their economic, political and social activities becoming ever more complex, including because of greater interconnections and interdependencies with other national states. The development of the state is frequently associated with three broad aspects. The first is its monopolisation of legitimate force combined with un/licensed violence towards some within its sphere and others outside it. The second is its role in the accumulation of wealth as a large part of its legitimation strategies, and the extraction of taxation from its citizenry as an element in this. And the third is distribution, essential as part of its legitimation activities.

2.7 There is in addition a fourth area, involving the regulatory aspects of the state apparatus. Although increasingly important, this is less frequently considered in conceptualising and analysing the state, perhaps because so many governments of both centre and right pronounce disengagement from such activities although in practice actually engaging in them. These regulatory aspects have been a marked feature in the South African context from the start of the European presence, from the eighteenth century on; and they have increased apace over time, propelled by the increasing scale of populations, technologies and activities, and the capacity as well as perceived necessity of regulation to ensure monopolisation and accumulation. Regulation in turn requires categorisation, for categorisations are the basis of being able to measure the effectiveness or not, not only of regulatory measures, but also of those to ensure monopolisation, accumulation and distribution. Regulation requires knowledge of things such as population size, income levels, employment and unemployment, the incidence of crime and responses to it, levels of health and illness and so on. Categorisation shows which groups or sections of the population are experiencing what levels or measures of these.

2.8 Monopolisation, accumulation, distribution and regulation have taken interesting forms in South Africa, and with a changing relationship between them over time. The African polities encountered by early traders and settlers were centralised and had the capacity for exerting extreme force, had a major role in accumulation regarding the controlling elite or oligarchy as well as chiefs or kings, and these things coexisted with considerable autonomy at local levels. Some of the then-new colonial states that came into existence were small and had just fleeting existence, with those with most longevity being the Transvaal or South African Republic and the Orange Free State. These too were centralised and oligarchical and were concerned more with the identification and regulation of people seen as Other than they were in matters of accumulation, with this leading to growth in their monopolisation aspects.

2.9 In particular, this concerned the heemraden and commando system. This involved graduated levels of local governance and legal powers, the heemraden, that also mapped onto the military command structure of the small, local conscription militias called the commando. All white men (largely but not exclusively of Boer or Afrikaner extraction) belonged by right and compulsion, including involvement in electing the different levels of the command structure; and those who did not belong were outside of all the structures of society in its public forms. Membership of ‘good societies’ indicating belonging, with these including other volk organisations and the church alongside the heemraden and commando.

2.10 The pass system was an early regulatory arrival on the South African scene from the eighteenth century on, with slaves required to carry appropriate documentation when they moved from place to place, with this then extended to any African person who came from outside the Cape, and it was then extended further through legislation concerning employment, and vagrancy if not employed, as well as pass laws themselves. The prevalence of the pass as a system of regulation based on and concerned with racial categorisation in all the colonial states spread from the Cape once the rapidly growing other settler states began forming. As might be expected, this occurred together with the growth of related forms of documentation concerning the bestowal, recording, use, presence or absence of passes, and also those concerning fines and other punishments for non-compliance. While there were different origins for the heemraden and commando system, and the pass system, they had similar regulatory concerns. Both were about control, both were predicated upon established and outsider groups and produced particular ratios of power, both were involved in classifying and arranging people in hierarchies in order to govern and dispose of their persons as much as their labour.

2.11 The heemraden and commando system not so much faded away as it was systematically dismantled by a series of measures introduced by Botha and Smuts administrations starting with Union in 1910. These included quashing the remnants (following a Boer Rebellion in 1913), and instituting central and regional forms of governance with offshoots at local levels, so removing the need for and the power structures of the older system. Monopolisation continued and was increased, but involved different ‘good societies’ and different systems of governance. Distribution of resources of all kinds was concentrated on the white minority. The trajectory of changes and developments concerning the pass system saw many extensions to its form and its scope occurring over time. By the 1930s it had become widespread, and from the later 1940s it was an omnipresent and immediate way of telling apart the legitimate and illegitimate presence of black people in putative ‘white spaces’. Black people were in fact necessarily always present because doing the productive, domestic, service and other labour in them and so they needed to be licensed; and this occurred on the basis of identifying, not so much who they were, as what they were, through categorising them in particular ways with racial categorisation as the basis of this.

2.12 As state regulatory aspects increased over the period of the apartheid era, so these took on various of the ritualistic aspects mentioned by Neville Alexander concerning the present situation. The different related kinds of documentation that black people were required to have with them added up to a significant amount of information about a very large number of people carried about on those (black) people’s persons in the passbooks. However, the functionaries who required this had little they could do with it apart from in the immediate contexts they demanded it in, because there was no dominating system at the core which synthesised and used all this information. At this point, state categorisation and regulation involving white (mainly) functionaries doing their jobs, and black people trying to go about their everyday activities and work, interfaced.

Regulation, categorisation & habitus

2.13 The term ‘habitus’ has been around for a considerable time. While it has been interpreted more recently in rather static terms as forms of cultural capital by Bourdieu and followers, as originally developed in the 1930s by Elias and others habitus is what is completely taken for granted and ‘the air we breathe’ in social life. What is conveyed in Smuts’ letters to May Hobbs about the racial order, for instance, has this aspect to it: it is just how things are, no question about it. The regulatory mechanisms of the pass system, which persisted in its most formal and draconian aspects until the mid-1980s, is based on there being clearly identifiable separate ethnic and racial groups with sharp differences between them that are incontrovertibly factual and ‘natural’, perhaps the most fundamental of the ‘air we breathe’ aspects of the racial order and the habitus that supports it.

2.14 This is of course not just a matter of the habitus aspects of white groups on the one hand, and black groups on the other. While notions of whiteness and blackness may be seen as foundational, South African society is composed by different ethnicities, language-groups and also that particular aspect of the problem of colour that Smuts’ letters also refer to, in the existence of a large and growing ‘coloured’ population. In South Africa, the coloured population is often described as though a separate racial formation, rather than the product of black-and-white sexual unions.

2.15 To think about habitus by recognising that there are different composing white populations, in particular regarding the language-groups of Afrikaans-speakers and English-speakers, is also to come up against something else that is seen as natural and intractable. This is a response that treats these people as though they are at basis Dutch and English (used in a generalised way to cover all the national groups in Britain), a usage which still persists, although the people so characterised often have nothing in their personal or family histories which connects them with any European birth-origins for some generations back. The categorisation of matters of ethnicity and race, then, may be foundationally based on a white and black ‘natural’ distinction, but this is sometimes extended to other differences, which are pulled into the category of what is foundational by being seen as characteristic of something that is ‘natural’.

2.16 Diminishment and contempt towards Others seems the basis. Categorising people around moral distinctions seen to be natural as well as racial has long origins in South Africa in terms of a convenient binary categorisation of people in – literally – white/black terms. The ensuing separations ensured most white people had little real knowledge of ‘them’ and what they were like, as persons and as collectivities. What was known was known by virtue of the categorisations used because these were defined by supposedly observable facts (eg. skin colour) constitutive of ‘people like that’. The membership categorisations involved was one that took for granted that racial categorisation encompassed everything important about to collectivities and therefore provided the best way to make sense of people and things. Thinking like this also gave the comforting sense to those in the would-be superordinate group that they really were superior, because those in the other group really were raw, savages, uncivilised, childlike and so on. A lack of civility towards ‘them’ was built-in, including the right to admonish and also to regulate and categorise.

3. The Racialising Processes & the Regulatory Trajectory of Change

3.1 The trajectory of change in South Africa over a long period is complex and can be seen overall to add up to a racialising process premised on regulation and categorisation. While this may not involve a completely intertwined and fully articulated set of sub-processes in the way Elias perceives for the civilising process in Europe, nonetheless the existence of increasing, and increasingly denigratory, racialisation and distinction on the basis of race perceived around skin colour and ethnicity and enacted it through regulatory mechanisms is a clear feature of how change has occurred. The movement has been from early and more fragmentary and shifting racial typifications, through the invention of seemingly more precise ethnic and related categories to support extended regulation, to the reduction of racial terms to a few highly negative words to stand for the vast complexities of many people in a massive system of ritualised regulation, to the institutionalisation of a state apparatus based on would-be ‘scientific’ race categorisations and separations, to the homeopathic spread of racial categorisation as the fundamental, natural, and in this sense seemingly value-free, way of thinking about people and proper place in the moral order of race.

3.2 Regulation and categorisation has been seen as a specifically biometric initiative of racial identification (Breckenridge 2014). Certainly this has been involved, but it is by no means the whole story, for the processes of regulation and categorisation at work and embraced by the state and a vast array of other organisational entities have wider remit than this and also deeper origins. Notions of ‘race’ and what constitutes it are a product, not a cause. One result is that categorisations based on race have entered the equal opportunities frame because enabling disparities in resources and opportunities to be identified and targeted: redistribution as a desired result requires categorisation to be accomplished.

3.3 It might be proposed that this is not so very different from in other societies across the world, for the juggernaut aspects of regulation and categorisation with respect to the role of racial categories as apparently fundamental aspects of how people are ‘naturally’ are occurring everywhere, and must be seen on a par with monopolisation, accumulation and distribution as key elements of the late modern state. After all, it is not just ‘race’ that has been reinvented and treated in this way, for ‘gender’ has also become ubiquitous and replaced sex as a way of indicating both biological and social aspects of categorisation, and with this category appearing as key in the ‘required information’ demanded in many areas of social life.

3.4 However, regarding South Africa, there are ways in which regulation and categorisation have occurred and are occurring in respect of race matters that are distinctive. Its specific history cannot be forgotten and reverberations of the different elements involved continue to mark the many ways in which racial regulation and categorisation are now occurring. This cannot be put on one side as incidental, for the effects still powerfully play out in regulation and categorisation and also face-to-face relations between people.

3.5 The presence of race as the component of regulation and categorisation is central, and its centrality now in large part derives from its earlier and persistent centrality over a very long period of time up to and including the 1994 democratic transition. There is no reason why race should have receded from this position, and many reasons why it has become a powerful factor in present-day regulation and categorisation both by the state and more widely. Succinctly, its omnipresence comes about because its earlier centrality has been built on throughout public life in South Africa and society, and its remit has-been significantly extended because of its usefulness in equal opportunities and redistribution terms.

I3.6 n terms of sociogenetic processes, this is perhaps a sign of what is beginning to happen elsewhere, that in governmental, institutional and organisational terms the technologically vastly expanded possibilities for regulation and with it categorisation have taken on something of a life of their own, with race and gender classificatory components within this. However, there are also factors that indicates that things will continue to take a different path in South Africa. Crucial here is that, as well as its different history, and its remarkable and distinctive transition to democracy, it is a country in Africa, with a history belonging to the continent, with diverse black populations, and has had black majority rule for over twenty years.

3.7 It is not surprising that issues have arisen concerning the future of the earlier ‘rainbow flag’ ideal of harmony between black, white and everybody in between. It has never been only a matter of black and white, and the processes of Othering are not easily contained. Neville Alexander discusses this using the concept of habitus and the Othering of outsider black groups and communities by established groups. His concern is the persistence and indeed increase of xenophobic responses to people from elsewhere in Africa who are seen as outsiders and outbreaks of extreme violence towards them. This is linked to a failure, not of accumulation, but of the re/distribution of wealth and the opportunities that go with it to large sectors of the population who remain outside the ‘good life’ enjoyed by others. Categorisation seems a route to redistribution, but it also solidifies outsider and established group identities. In turn, this has impacted with negative force on the taken-for-granted habitus-connected aspects of how people think of and treat Others.

3.8 This brings a salutary reminder of that ingrained assumption of whiteness, in seeing itself as central when it is actually not. Race both is and is not ‘real’, or rather it is as real as it is made. And it can be made with other elements than black and white, and anyway neither of these are homogeneous groups. Race and hierarchy also includes black and black and established and outsider divisions. The ‘new racialisation’ now occurring is of this kind. Concerning the role that race matters continue play in South African life, an appropriate closing observation about the racialising process is that,

“there is no doubt at all that this focus has indeed shifted ‘back’, as it were, towards the contending multiracial traditions. The fact that the relationship between unavoidable national South African identity and the possible sub-national identities continues to constitute the stuff of political contestation… demonstrates clearly how tenacious the hold of history is on the consciousness of the masses of the people. The most optimistic conclusion we can draw from the consideration of this ongoing contestation is that it is continuing, that no ‘end of South African history’ is in sight.” (Alexander, 2013: 13)

4. References & Reading

Neville Alexander. 2013. Thoughts on the New South Africa. Auckland Park, South Africa: Jacana.

Keith Breckenridge. 2014. Biometric State: The Global Politics of Identification and Surveillance in South Africa, 1850 to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eric Dunning and Jason Hughes. 2013. Norbert Elias and Modern Sociology. London: Bloomsbury.

Norbert Elias – specifically on de/civilising processes

Norbert Elias. 2012 [1939]. On the Process of Civilisation. The Collected Works of Norbert Elias, Vol. 3, Dublin: UCD Press.

Norbert Elias. 2013 [1989]. Studies on the Germans. The Collected Works of Norbert Elias, Vol. 11, Dublin: UCD Press.

Stephan Mennell. 2007. The American Civilising Process. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Useful work on social change specifically in South Africa includes:

George Fredrickson. 2000. The Comparative Imagination: On the History of Racism, Nationalism, and Social Movements. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Jamie Frueh. 2003. Political Identity and Social Change: The Remaking of the South African Social Order. New York: SUNY Press.

Adrian Guelke. 2005. Rethinking the Rise and Fall of Apartheid: South Africa and World Politics. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Paul Maylam. 2001. South Africa’s Racial Past. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Liz Stanley. 2017. The Racialising Process: Whites Writing Whiteness in Letters, South Africa 1770s-1970s. Edinburgh: X Press. This essay contains a much shortened and revised version of Chapter 10 in this book.

Last updated: 13 May 2021