Lady Anne Barnard to Henry Dundas, 11 June 1798

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2020) ‘Lady Anne Barnard to Henry Dundas, 11 June 1798′ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Barnard-Dundas-1798/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

cape of Good Hope

June 11th – 1798It seems to me an age since I wrote to you my good friend, but your silence to me so long and continued begun to make me very much doubt whether my letters were not rather plagues than pleasures, and as I was with holding ^them^ from several very dear friends, that I might heap the more on you (ungratefull as you appeard to be) I begun to think a little pause at least could do no harm; unreadable – of late however tho I am still without any thing under your own hand I have receivd thro Lord Macartney & Margaret so many kind & flattering messages, apologies for your silence & requests that I woud continue to write to you that I will give doubts to the winds & as the winds at the cape Blow very fiercely off shore my distress will be half way across the ocean before the sentence is finishd allmost at the present I cannot add more however, this much I hurry off with my blessing to you & Lady Jane but the ships are to sail sooner than I expected And I wish to send you a long & comfortable account of our tour into the interior of the country the particulars of which I kept memorandums of, but have no time now to finish it it shall arrive by the China ships expected shortly & which may possibly arrive in England as soon as this and till then god Bless you All –

Anne Barnard

all are well here – every body that you wish well to &c – Lord Teignmouth will carry this, he and his family were on board the Britania when it was struck with lightning there is a doubt of his being too late for the convoy at this moment, the admiral is in a Hurry to get all the ships off – adieu – adieu –

(Anne Barnard to Henry Dundas, 11 June 1798, NLSA/Robinson 1973: 161; the spellings, insertion, crossing out, capitalisation and punctuation are as in the original)

1. Introduction

1.1 This letter, dated 11 June 1798, was one of many written by Lady Anne Barnard to a senior British politician, Henry Dundas, who over the period of her extant letters to him was a government minister under William Pitt the Younger. He had become the minister responsible for the War and the Colonies, a new government position second only to the Prime Minister himself. He will have received the letter around three months after this date, sent by the uncertain means of a sailing ship on a long passage in rough waters in times of war. Dundas has recently become notorious, infamous even, because of his role in holding up the formal abolition of slavery in the UK Parliament for what seemed to him at the time good reasons concerning the long-term success of this legislation. Be that as it may, those events had yet to happen when this particular letter was written.

1.2 It is one of the shortest of Anne Barnard’s surviving letters to Dundas, and also the least eventful. It is written in a very low-key way, it appears entirely inconsequential, as well as seemingly containing nothing about whiteness and race matters. But reading it like this is the product of myopia, from focusing too much on the letter itself in a vacuum, from ignoring its fellows, and also the context in which they were written as well as their relationship to each other. In fact, inhabiting its sentences and paragraphs, its uncertain capitalisations, its dashes, its formalised ways of writing, are the growth of empire, the seeds of colonialism, the happenstance extensions of governance, the complexities of race and ethnicity, the paradoxes of the settler gaze.

1.3 It is a letter which acts as a small vector for large matters of empire, colonialism and whiteness, then. So it needs to be taken seriously.

2. Context

2.1 The Dutch East Indian Company (VOC) had had a dominating presence in what is now the Cape since the mid-17th century and through its activities the colonial governing power was the Netherlands. At the same time, Britain had a strategic ‘interest’ in this area, because of its location on the sailing route from Europe to India. During what are now known as the Napoleonic wars, in 1795 France occupied the former provinces of the Netherlands, and following this the Batavian Republic was declared there. After a relatively quiet period, war resumed including on the trade routes, and when Dutch militia were defeated at the Battle of Muizenberg near Cape Town Britain took over administration of the Cape. This occurred in part because of these wider matters, but also because the VOC through a variety of factors became bankrupt and in a state of near collapse; it was nationalised in 1796 by the Batavian Republic, and dissolved in 1799.

2.2 A military British military presence at the Cape was established, followed in 1797 by a civilian administration under the governorship of a senior diplomat with a high profile successful career, the former Sir George Macartney (who became a Baron in 1795). Lord Macartney was appointed following his successes in Madras and China by the politician Henry Dundas, who as noted earlier was the first Secretary for the Colonies & War under the Prime Ministership of William Pitt the Younger.

2.3 Dundas had also appointed ex-army Captain Andrew Barnard as Secretary to the Cape, a new, senior, but undefined administrative role working directly with the governor. As was customary at the time, such positions were appointed in part because of competence and in considerable part because of a widespread system of patronage for men who had a particular career pattern and class background. Andrew Barnard seems to have been amiable, hard-working and charming, but not particularly outstanding, and he was the recipient of this largesse because of the influence of his wife, the former Lady Anne Lyndsay, a Scot and a long-standing friend of Henry Dundas. Dundas had earlier been one of the many suitors she was on friendly terms with but did not wish to marry, and they remained close.

2.4 Unusually for the time, when aristocratic women generally stayed in Britain when their husbands and fathers administrated far-flung parts of a growing empire, Lady Anne Barnard sailed with her husband to what was then the Cape. They arrived in May 1797. Because Governor Macartney’s wife was one of the stay-at-home women, she became his official hostess. Anne Barnard was also ‘a writer’, of diaries, a journal for an outside readership, letters, a memoir, and she sketched and painted well too, and she used all of these mediums to leave a record of her five year period at the Cape.

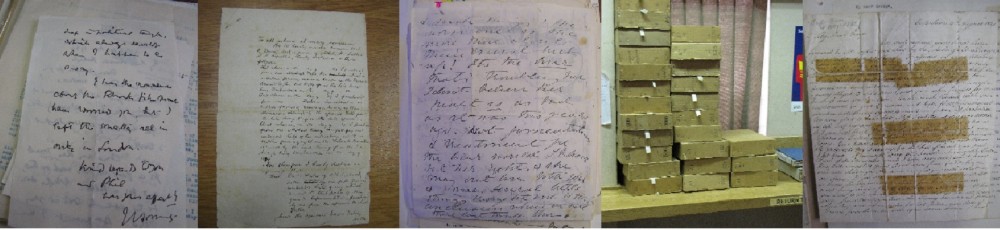

2.5 There are around 30+ letters, some extremely long (4000 to 9000 words long), that Anne Barnard wrote to Henry Dundas. This was not just a matter of friendship, but involved her writing what are in effect reports or dispatches, providing him with detailed information about people, places, the state of things, including the possibilities of the Cape for future colonisation and agricultural development. While she sometimes protested that she was just a woman and women’s views were not to be taken too seriously, the lady doth protest too much, for the length and sustained nature of the correspondence indicates something very different, that she knew her observations were important and likely to be taken political account of. In addition, as she was a woman of lively mind with great interest in other people, so her letters provide much interesting detail about ordinary people and everyday life at that time in that place which is not available in other sources.

3. Pretext

3.1 Unlike other letters to Dundas, that of 11 July 1798 was precipitated by the immediacy of events that were unfolding as it was being written – the relatively small events of time and tide and winds. When it was written Anne Barnard, her husband and a small party including some servants had not long returned from the four week tour of ‘the interior’ it mentions. It would seem there was originally intended to be an epistle or letter-diary in which she would write to Dundas about the daily events that occurred and the people they met, to give him an idea of the state of things relevant to British governance. While she writes that this was unfinished, this of course indicates that it was started but needed tidying up or extending from the memorandums she mentions, though it seems never have been sent to him and is no longer extant.

3.2 The tour is in fact covered by a similar piece of writing which also takes the form of a letter-diary, written to Anne Barnard’s sisters Margaret and Elizabeth. But instead of this or one of her ‘usual’ dispatch-like letters, what she wrote to Dundas in the particular circumstance was something shorter, a kind of covering letter, explaining why there was not a ‘usual‘ longer letter.

4. The text

4.1 The 11 June 1798 letter is short and focused. It is resolutely mundane to the point of seeming uninteresting. It was written as it says with haste because a ship was unexpectedly sailing. Indeed, it concerns haste upon haste. First Anne Barnard writes that, “the ships are to sail sooner than I expected And I wish to send you a long & comfortable account of our tour into the interior of the country … but have no time now to finish it…”. Second, there is an addition, a PS without being signalled as such: Lord Teignmouth may be too late to catch the convoy because “the admiral is in a Hurry to get all the ships off – adieu – adieu –“. Time and tide and a good wind for sailing wait for no letters.

4.2 The hastily written PS at the end comments that “all are well here – every body that you wish well to &c – Lord Teignmouth will carry this, he and his family were on board the Britania when it was struck with lightning…”. The former John Shore was created first Baron Teignmouth in 1798. He was a revenue official of the British East India Company and became the Governor-General of Bengal from 1793 to 1798. At the point the letter was written he was returning with his family from India.

4.3 The ship Britannia was a merchant vessel that had been captured from the Dutch earlier in 1798, while the incident involving lightning has not been traced. It seems to have been the ship on which the Teignmouths travelled from India to the Cape. The particular Admiral who was responsible for the rush in catching a good wind has also not been traced.

4.4 The 11 June 1798 letter, then, is a replacement for the ‘real’ but incomplete intended letter based on ‘memorandums‘ for Dundas, and is more of a note than a letter of the kind she otherwise wrote to him. The opportunity to dispatch it came with the departure of the Teignmouths and their ship, and it happened more precipitously than anticipated, which was what contracted her original intention and led to the production of this short note-like piece of writing. And it should also be noted that this non-existent but ‘real’ letter was in fact a quasi-letter because actually based on a quasi-diary.

4.5 Most of the first part of the 11 June letter consists of explanation, apology, solicitude and conventional politeness. The substantive point conveyed is that, “And I wish to send you a long & comfortable account of our tour into the interior of the country the particulars of which I kept memorandums of, but have no time now to finish it”. While this is slim pickings in the way of substantive content, it does contain something important about the writing practice Anne Barnard was engaging in. This is that she had kept memorandums of the tour, and was engaged in ‘finishing’ these, which most likely means she was writing them up into daily entries of the kind that forms her account of the tour for her sisters.

4.6 This is followed by her signature, in the form of a statement of her name with no salutation or sign off. What follows it acts as a PS, as already indicated. It is along the same lines as the previous part of the letter, providing an explanation of how the letter is being dispatched and the reason for the extreme haste. And this haste is reinforced by its final words: “adieu – adieu –”.

4.7 Although the letter’s content of explanations and apologies appears utterly mundane, nonetheless when taking into consideration the wider aspects that have been sketched in here, it can be seen to act as a vector for structural forces and developments, concerning the governance of India and its ‘provinces’, the mercantile and also quasi-imperial role of the British East India Company, the collapse of the VOC, the Napoleonic wars and their reverberations elsewhere in the world, competition between European powers and rise of the Age of Empire, the stirrings of settler colonialism.

4.8 It is also the meeting ground between these things and another ‘something’ that is not visibly there but lurks on the pages of that intended but never completed diary-letter that is so casually mentioned as ‘memorandums’. If this was to have been anything like the parallel version Anne Barnard sent to her sisters of ‘the tour of the interior‘, then the complexities of race and ethnicity and the paradoxes of the settler gaze are also there; so whiteness is thereby there in one of its earlier incarnations and with attendant complexities. Her daily accounts of the tour contain the most detailed of her comments on race and ethnicity around the different kinds and orders of people that she came across and her descriptions of and responses to them. They show that matters of ethnicity at that time could take precedence over those of race, that negative feelings often inhered more in the former than the latter, and that the gaze of this particular letter-writer in writing whiteness was a complicated and nuanced one.

5. What then…

5.1 The June 1798 letter was dispatched and it arrived with Henry Dundas in due course, most likely around mid or late September 1798. A number of others followed, which resumed their more usual character of being reports or dispatches and extremely long and detailed. They continued until the Cape returned to Dutch rule, when in 1803 Anne Barnard left for Britain, and Andrew Barnard remained for what they thought would be a short time before the Batavians took over, but which actually took more than a year.

5.2 Under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens the Cape was returned to Dutch control in 1802-1803. When France resumed the war, this invalidated the Treaty and Britain occupied the Cape again in January 1806 after the Battle of Blaauwberg. Subsequently the Boer Republics proliferated then condensed; Natalia became the British Natal; and the Transvaal and Free State formed. The settler-colonial hordes began to arrive, doing so in numbers from 1820 on, more extensively still from 1850 on.

5.2 Andrew Barnard had lost his Secretaryship when the Cape was returned to Batavian control. No further position was offered him in spite of his and his wife’s efforts – the governing ministry had changed, Pitt and Dundas were out of office and Anne Barnard’s lines of influence in the encouraging patronage had foreclosed. But when Dundas returned to political office, Barnard was reappointed to his post as Cape Secretary. His health was uncertain, but no British-based post was offered. With reluctance he returned in early 1807 without his wife, who stayed to lobby for a British post for him. Having had stomach and bowel problems for some time, Andrew Barnard died not long after arriving back in the Cape.

5.3 Anne Barnard continued her interesting way through a long life. She adopted her husband’s illegitimate daughter, conceived with a black servant in a Cape Town family he was friendly with when he remained at the Cape and Anne had left for Britain. She also looked after the daughters of his two illegitimate sons from before she married him. She entertained much, painted much, wrote much. Her letters, her diaries and her journal remain of deep interest now.

5.4 For details of WWW research on the Barnard letters, see the Lady Anne Barnard Letters entry on the Collections pages, which also provides a short reading list.

Last updated: 17 September 2021