When is an author? On Mandela’s books

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2020) ‘When is an author? On Mandela’s books’ Whites Writing Whiteness www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/curiosities/When-is-an-author/ and also provide the paragraph number as appropriate if quoting.

1. When is a book by someone, by an author, by its author? This is an awkwardly phrased question, because it gets at something awkward and curious about the character of authorship and through this connects with related questions about letters and cognate forms of writing.

2. In the case of Nelson Mandela, a number of books bear his name as author but where the contents have actually been compiled by other people. Yes, his words as present in letters, notes, speeches and interviews have certainly been used. But no, the act of authorship which produced the product that is the book these are in was not his, but that of some other person or persons. An example here is Conversations with Myself, which is ironically entitled in this respect, for although a very interesting book it has been put together and in this sense has been authored by other people and not by Mandela. The words may be his, by him, but the book is not, for there are two interrelated but not coterminous notions of authorship going on here.

3. Another example is situated just the other side of the authorship line, having similar origins in a wide variety of different kinds of writings by (and a few about) Mandela, but which appears under the authorship of the Nelson Mandela Foundation. It is A Prisoner in the Garden: Opening Nelson Mandela‘s Prison Archive. The words are Mandela’s and so are the photographs, but it is represented differently with regard to matters of authorship: by the Foundation, not by him. So why the difference? Why should one be presented under Mr Mandela’s name, and the other not?

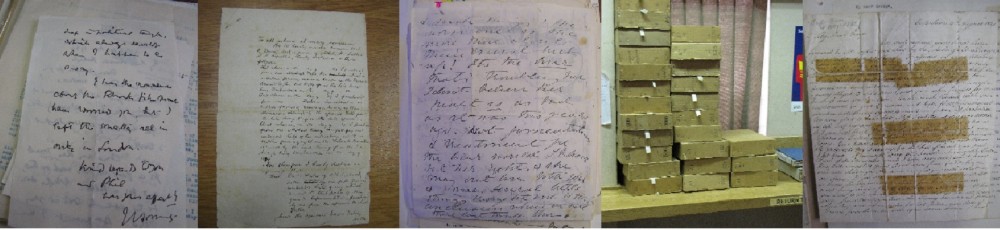

4. A Prisoner in the Gardenis a beautiful book. It contains a large number of photographs, both things that originated as photographs, and also photographs of letters, diaries, calendars, notes, legal documents and more, accompanied by a narrative text that is expressed quite sparely and is all the more powerful for this. It is striking in a more than visual sense, for the beauty of the images of the many documents it provides sits uneasily with the fact that they emanate from and testify to nearly 30 years of incarceration in much less than beautiful circumstances. The representational visual beauty of the materially really awful.

4. A Prisoner in the Gardenis a beautiful book. It contains a large number of photographs, both things that originated as photographs, and also photographs of letters, diaries, calendars, notes, legal documents and more, accompanied by a narrative text that is expressed quite sparely and is all the more powerful for this. It is striking in a more than visual sense, for the beauty of the images of the many documents it provides sits uneasily with the fact that they emanate from and testify to nearly 30 years of incarceration in much less than beautiful circumstances. The representational visual beauty of the materially really awful.

5. A Prisoner in the Gardenis described as a set of ‘living records of 27 years in prison’ in bringing together items scattered in many archives and personal collections, with this facilitated by the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory and Commemoration Project in association with its parent body, the Nelson Mandela Foundation. The Foreword is by Mr Mandela himself, commenting that the Centre was founded to locate, document and facilitate access to the many archives that contain documentary traces of his life and those associated with it. He concludes,

“Anyone who has explored the world of archives will know that it is a treasure house, one that is full of surprises, crossing paths, dead ends, painful reminders and unanswered questions. Very often, the memories contained in archives divert from the memories people carry with them. That is its challenge. And its fascination. Engagement with archives offers both joy and pain. The experience of viewing my prison archive has been a personal one for me. Readers are invited to share in it” (Prisoner, page 9)

6. The distancing in this statement is interesting, always supposing that Mandela himself wrote it rather than assenting to a draft produced by a third party. It states that ‘anyone who has explored the world of archives’ would have experienced the complicated reactions described, and he too had the experience of viewing his archive in a way where there is a divergence from what is in the archive and ‘the memories people carry with them’. The memories were in his possession, but the documentary materials in the archives were not. This is a clue to the question of authorship, that these materials were not ‘his’ but assembled from many places and therefore when he saw them together it was as it were for the first time and as a relative stranger, as a reader, in effect. As he says, “The experience of viewing my prison archive has been a personal one for me. Readers are invited to share in it’ (Prisoner, page 9).

7. The Mandela Centre of Memory and Commemoration Project did its work as part of launching an Exhibition, which had the same name as the book. It was in this context that the documents and photographs it contains were shown to Mandela for him to examine, a process during which he also reminisced about them. When the Centre was launched, this was as part of Mandela announcing that his prison archive would be systematically made available, so the Centre, the Exhibition, and also the book from the Exhibition, all came to fruition together even if they are not entirely coterminous.

8. Another clue about authorship exists here, that the Project was conceived from word go as a means of providing public access to documentary materials that were at basis seen as public documents, or rather as documents that should be seen as a public ones because of their importance within the life of Mandela. All those years that Mandela experienced being incarcerated and cut off, but at the same time under constant surveillance, has reverberations in terms of the relationship between the public and the private man. In effect, the private man has his memories in his possession, while the public persona uses the written traces, removed from him, as though an outside reader.

9. The result of the exhibition and book is presented as the reader being given privileged access:

“Inevitably, the official record has marked emphasis, as well as silences, reactions and contradictions, and an investigation of these is often richly rewarding, using even further archival clues and materials. This book explores many of these paths, often leading the reader into parts of the Prison Archive that lie outside the official record, and yet, in many instances are interweaved with state archives” (Prisoner, page 21)

10. Relatedly, the Mandela Centre of Memory and Commemoration Project has been concerned with ‘opening the archive’ in a further sense. Recognising that the relevant materials from Mandela are scattered and often inaccessible, the Exhibition and this book are closely linked to Centre’s intention to locate them all and make information about them available. Another clue about authorship exists here, for this is the work of the Foundation and those who staff its Memory Centre, with the book, like the Exhibition, being a factor in its work, rather than any in autobiographizing activity by Mandela himself.

11. On the Nelson Mandela Foundation website, its pages are primarily organisational information-giving ones – it is not a ‘working’ website in the sense of readers being able to use it to generate research-type materials. But it does have a useful archive section – for this, go to https://www.nelsonmandela.org/content/page/collections

12. Visitors are informed here that in the fullness of time it will provide not only information about its own holdings, already on its pages, but also list the many sources that are available world-wide, something which is still in progress.

13. So what is authorship in the context of this opening of the Mandela archive in the A Prisoner in the Garden book? What appears in the book, and also the Exhibition, is a very managed set of documents. They may seem as though resulting from drawers being casually emptied, but actually they have been carefully selected and carefully presented to tell a particular kind of archive story. The assemblage process is not visible, but what is assembled is certainly so and on an international stage. This is not privileged access, but a very managed and orchestrated one.

14. Important questions consequently arise about the ontology or composition of this particular variant of an archive. Whose archive is this, precisely, Mandela’s or the editor’s? What is the order of ‘the collection’ as represented, what principles underlie the structure of what is provided to readers? Are these documents singular, on their own and unconnected, or are they part of a temporal or political or personal sequence? Concerning the different locations they were found in, were different kinds of materials located in different archives? Are all of the content dated, or do some have dates supplied by what is put before and after them and so being an editorial product? And the questions go on.

15. These materials look like the contents of an archive are supposed to look, with different kinds of documents featuring on all of the pages. But in fact the contents of most archives are not like this. Most archival stuff is shabbier, it makes little sense, meaning cannot be attached to particular items or even numbers of them without much struggle. There is, by contrast, clear sequence and series to the contents of the Prisoner in the Garden book, but when looked at closely, this is a world away from the archival sequences they have been selected and photographed from, hundreds of them ranging from the very formal and inaccessible to the fabled emptying of the back of drawers.

16. A further twist to questions of authorship and the curious complexities that inhere in the production of a book-as-published-archive is provided by Nelson Mandela’s prison letters.

17. The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela is edited by Sahm Venter, a senior researcher at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, and can be seen as a companion to and extrapolation of the two books above. The Prison Letters is very smartly turned out, with a beautifully designed dust jacket, a set of photographs, useful appendices, and an excellent index. What results is an important contribution to scholarship on the life and times of Nelson Mandela. However.

18. As discussed in the book (Prison Letters, pages xiii-xv) and noted above, Mandela‘s papers are now in many archive collections. A result is that this edited collection has taken ten years to put together. Listings of the letters it contains are provided (Prison Letters, pages xiii and 601-3). Most of the actual letters are in the National Archives of South Africa, the rest in various other locations. A large number of the transcribed letters were in fact originally transcribed by Mr Mandela himself. This is because he copied his letters to people up to 1971 into hardcover notebooks before they were given to the prison authorities, while later in his imprisonment other letters were transcribed onto notepaper, because he knew that many or even most would not be sent on to their addressees but filed into oblivion. This was because of petty censorship, but more particularly because of routine activities designed to wear down the Robben Island political prisoners emotionally and mentally by isolating them well beyond what imprisonment ordinarily did. These notebooks were later confiscated, and then in 2004 were handed over by the police officer who had them and are now in the possession of the Nelson Mandela Foundation.

19. The letters in this collection are presented chronologically. There is no count given but there are probably around 250-300 of them. It is also not clear whether these are the total number of the extant letters Mr Mandela wrote over the period of his imprisonment, although as the word ‘selection’ is used in introducing the edition it is possible, even likely, that there are more in existence than have been included. If so, it is a pity that the basis for selection is not discussed, as clearly it will have been important in shaping the account given overall by the letters provided. Some detail – but not enough for those of us particularly interested in letters and archive collections – is given about the editing process, with its main aspects described as:

“The letters in the selection have been reproduced in their entirety apart from in several cases where we have omitted information in the interests of privacy. To avoid repetition, we have also omitted Mandela‘s address from nearly all of the letters… We have reproduced the text exactly as Mandela wrote it apart from correcting the odd misspelt word or name… very occasionally adding or removing punctuation for ease of reading… Mandela often wrote letters in Afrikaans and in isiXhosa, the language he grew up speaking, and we have noted which of these letters have been translated into English for inclusion in this publication. Some letters were also typed by prison officials and we have also noted these instances…” (Prison Letters, page xiv)

20. This says that the letters have been reproduced exactly – but then it provides a list of the ways in which they have been subject to editorial amendments. Are these Mandela’s letters? Is he their author? Not exactly, but very likely enough so with regard to most content, although the changes are likely to have impacted on many aspects of nuance. He was the letter-writer; he is/not the author exactly and precisely.

21. The openings of each main sections of the book, and some linking passages within them, provide a narrative of ‘at the time’ information about events and persons. This is necessary for the general readership anticipated for the editors and publishers, and also very helpful for anyone without a detailed background in South African politics of the day. In addition, biographical information on all the people mentioned is given in footnotes attached to each of the letters; and at the end of the book there is a helpful glossary which gives some information about organisations and also provides more detailed information about the key people who are the addressees of letters. There is also a prison events timeline, and a map of South Africa and brief descriptions of places of relevance; and these too are at the end of the book. A great deal of work has gone into this. But what more precisely is it?

22. These are the letters, not of a public nor even a private man, but a man who was allowed to have just an organisationally orchestrated and sanctioned face. That is, the total surveillance that Mr Mandela was under meant that his letters were always and entirely written under the gaze of outside eyes beyond those of the letter-writer and his addressees. And similar but always ‘at a remove’ controls exerted over letters that people sent to him in the form of an official eye and hand cast over them, in suppressing some, sending others, copying some, destroying others.

23. This is perhaps in a limited respect not so different from letter-writing in earlier times, which were seen as having collective purposes beyond the particular writer and addressee. But of course the panopticon aspect here was designed to control, and intrusively did control, the dialogical aspects of letter-exchanges by reducing such exchanges to a bare and censored minimum. Many of the letters have had their dialogical aspect limited by intruding a third party as a reader and often as copyist between writer and recipient, impacting on terminology and content on the part of the letter-writer; or negated by destroying a letter or filing it and never sending it. A result is that the sequences of letters referred to in quite a few of them were in fact often not the sequences that were experienced either by the addressees or by Mandela himself, because ‘interruptions’, removals of letters, as well as excisions of sentences or paragraphs or passages, were imposed but not told about by prison authorities. Another result was that Mandela did not know what this ‘public organisationally-sanctioned Mandela’ had written; and relatedly the addressees did not fully know what the ‘private Mandela’ who was a father, grandfather, friend, wife, colleague, might have written and intended.

24. By definition, letters are written so as to be dispersed, and their writer will never have seen them all altogether. The Mandela prison letters are an interesting exception to this general rule. That is, because of his writing practices in the context of imprisonment, in keeping handwritten copies of everything in notebooks or on letter-paper, these letterswouldin fact have been seen as ‘the collected prison letters of Nelson Mandela‘ by Mr Mandela himself. But were they just left on a shelf in his prison cell? Or did he read them over after the event of sending? If so, was this to enhance the vagaries of memory with the certainties of words on paper? Or to remind him of people and places and feel less disconnected? But perhaps he simply left them. And regarding both possibilities, it is interesting to conjecture whether and in what ways his letter-writing style might have changed over time, although perhaps it didn’t change because the specifics of who he was writing to and about what were more important than matters of style and composition

25. The Prison Letters is an edited collection with an antecedent existence, then, indeed a number of them. Because of the prison service’s surveillant gaze and its ‘grind them down, cut them off, remove them from any outside’, many of these letters in their original forms (i.e. not transcribed by Mandela into notebooks, not typed up with excisions silently made by prison officers) had been already collected by the prison authorities even before they were collected into archives in South Africa and elsewhere, and long before the editor of this present edition went about her collecting and selecting work.

26. Before this, Mr Mandela composed his letters as a dispersal but retained copies as a personal collection; the prison authorities produced a collection of them, including typescripts of those that were sent on; the people who received the letters that they did kept them in a collected form; formally constituted archives later collected them; the editor collected them and transcribed, or re-transcribed those that had already been transcribed, into a form suitable for publication. The sedimentation effect is tremendous and there are multiple transformations of both ‘the letters’ and ‘the author’ involved.

27. This edition of Mr Mandela‘s prison letters is certainly an important milestone in encouraging a more detailed investigation of the ideas and practices articulated by Mandela during his long years of imprisonment and its imposed curious public/private/organisational frame that surrounds these writings. But it adds to the curious ‘words by Mandela authored by others’ character of works ‘by’ him, rather than confronting this.

28. So, when is an author? In the case of Nelson Mandela we are yet to find out.

29. And what of letters and authorship? Many of the same issues exist, in particular with regard to editorship and what has been identified here as its authorial aspects. Three aspects of this are worth noting. Published letters are frequently both selected and collected editions. They are not the entirety of letters that might have been included in a selection; and they are collected together from disparate sources, leaving behind their fellows. Often this is not commented on let alone discussed in detail, along with other editorially-made ‘silent’ changes, including ‘correcting’ mistakes, and providing either no or insufficient information about such editorial activities. And in such editions there is often long introductions and substantial amounts of footnoting and other interpretational work on the part of editors. These are usually presented as having an ‘it is so’ character, providing ‘the facts’ for readers, although often they are simply interpretations and other interpretations might well be possible.

30. The result overall is to close down the possibilities for readers actively reading and interpreting for themselves, because shaping and guiding the content. When is an author here? The line between authorship and writing slips and slides; and by doing so it raises the related question, when is a reader? Is a reader still reading in a meaningful sense when a text is closed like this, when everything to know is handed on a plate as it were pre-digested by an anxious and over-active editor? This is an equally tricky question and permits of no easy answer.

References

Nelson Mandela. 2011. Conversations with Myself. Pan.

Nelson Mandela Foundation. 2005. A Prisoner in the Garden: Opening Nelson Mandela‘s Prison Archive. Penguin.

Sahm Venter. ed 2018. The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation/WW Norton & Company.

Last updated: 12 January 2020