Waiting

The mindset or worldview of whites in South Africa in the period before the democratic transition in 1994 is frequently summarised around the word ‘waiting’. It has formed a theme, not surprisingly, in much writing about South Africa; Waiting for the Barbarians is the title of JM Coetzee’s famous novel of 1980 on this, Nadine Gordimer’s 1981 novel July’s People is about the aftermath when waiting ends, and Vincent Crapanzano’s 1985 study of whites in a part of the Western Cape also has Waiting as its title and central motif. This gives rise to an interesting question – why didn’t the large black majority rise up against the oppressor white people and slaughter them in the way that the ‘waiting’ idea fears and anticipates? A bit of context here is that in the 2017 census, the population of South Africa was 58 million, 92% of which was black, coloured or Indian and 8% were white. In the 1904 census, with a serious underrepresentation of the black population, the overall population was 5.2 million, black, coloured and Indian were 78% and the white group was 22%; more realistically, the white population was probably about 10-12% of the total. And going back further in time, both the overall number of white people and whites as a proportion of the total population were even smaller.

So, why didn’t the large black majority just get rid of the oppressor group? The beginnings of an answer can be found in considering some of the factors involved in why Crapanzano’s book got it wrong, that the 1994 transition did take place, and it was preceded by discussion and debate rather than by massacre and terror. Crapanzano is a US anthropologist and his study reveals some of the limitations brought with this: his outsider moral view was of a binary divide between black people and whites, with whites very much at the negative end of the binary, and with the fears of a particular white community whose members at the time felt beleaguered being taken as an accurate reflection of the circumstances prevailing, that their fears were realistic rather than the long-standing ‘waiting’ mentality that can be found going back to the 1840s or even before.

So the answer is on one level a simple one, that the actual realities of white and black relationships in South Africa were more complicated than this. And the black population was never a one-dimensional homogenous one, but composed of peoples of different ethnicities, with different histories, different present circumstances, different beliefs and social practices, different views of what was happening. But of course, without knowing the detail, without knowing what these complications actually were, it is not really an answer. It is often said that the devil is in the detail, and it is on such detail that historical knowledge rests, because this detail is the bedrock of how knowledge of the past is pieced together. Ultimately, claims made about the past depend upon the traces that remain. And the further away in time, the more that those traces are documentary and consist of all the things that be Whites Writing Whiteness project is concerned with.

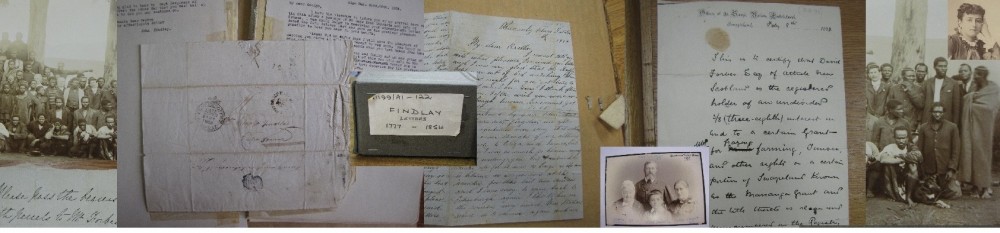

In this connection, for the last couple of weeks there has been much work preparing for an annual lecture to a group of Scottish Highers history students whose specialist subject is South Africa. This year’s lecture will focus on how to interpret what the plethora of extant documents indicate about matters of race and racism. In it, eight different documents covering the period from 1835 to 1933 are being focused on, looking at how to analyse and interpret each of them, and then considering what they add up to. The documents in question are, in chronological order, an indenture, a contract of employment that doubled as a pass, a photograph of organisational officials, a letter requesting someone to act as a labour recruiter, the amended draft of an official document, a ‘celebrity’ photograph, a crucial piece of legislation, and a letter presenting some racial and ethnic ‘descriptions’. These and many more examples like them are the details that form the bedrock: they are ‘the traces that remain’, and an interpretive account needs to reckon with the fact that what they indicate is less a consistent narrative, and more one that is inconsistent, varied, contradictory, complex. There is the more or less consistent development of racialised categories and formal edicts at a meta and structural-level; but at the same time there is something more complicated and contradictory going on at local levels.

Last updated: 15 November 2019