The ‘I-perspective’, Mozart’s letters and Elias’s argument

This week’s blog focuses on discussing the places in Elias’s book on Mozart and the sociology of genius where he provides actual quotations, rather than just referencing information alone. Such a discussion may seem out of place in the context of a project concerned with the representation of race by white people in South Africa. There are two reasons why it is in fact connected. The first is that Norbert Elias is one of the few social theorists to have advanced a sustained analysis of sociogenesis and the unfolding processes of social change at a society level interfacing with changes at an interpersonal level. His work overall therefore provides many important insights which can be drawn on in better understanding how the processes of change occurred and were represented in letters and diaries and other documents of life in South Africa.

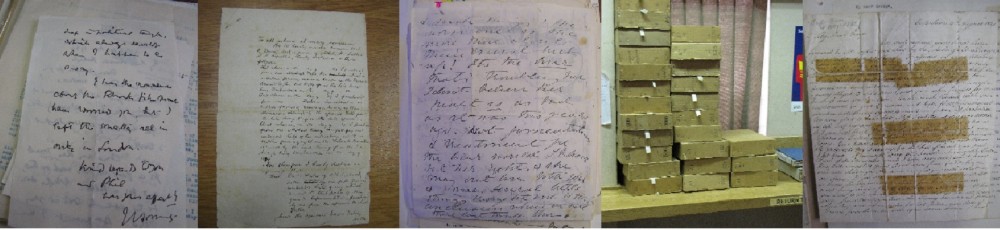

The second is that exploring the methodological aspects of how Elias engaged with Mozart and his letters provides some useful pointers for research on published collections of letters more generally. Is the focus on the letters, or on the person who constructed the collection, or on the researcher who subsequently uses them? What aspects of such published collections should be focused on? How to handle a body of data that consists of hundreds or perhaps even thousands of items? How to begin, what aspects to follow up on, what changes to make when avenues of exploration prove unfruitful, what kinds of theoretical ideas are helpful in understanding what is being read? It is regarding these methodological questions that the interconnected WWW blogs concerned with Elias on Mozart and the sociology of genius have been written.

A total of 62 letters are referenced by Elias in his book, while there are sometime shorter and sometimes longer quotations from some 27 of these.

The repeat of a quotation from a letter by Count Arco (Court Chamberlain to Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart‘s employer the Archbishop of Salzburg) acts as an overarching guide to ‘what happened’ and is a kind of instruction to the reader. The quoted remarks appear as a statement of fact and have a prophetic purpose, that the Vienna public was fickle and that fame would not be achieved because public demand would change. The first time this appears, it is the very first letter that Elias quotes from. The effect is that, the second time it is quoted from, this serves as a reinforcement of an already built-in knowledge of the failure of Mozart’s attempt at independence in Vienna.

The quotations from letters by Mozart himself (as an earlier blog noted, there are a good few from his father, and just small numbers from his mother, cousin and Arco) are limited and used in the following ways by Elias to propose that: 1. Mozart was over-sensitive and needy as a child and remained emotionally vulnerable as adult. 2. As a child and adolescent, his life and activities were dominated and controlled by his father on the different tours they engaged on. 3. He over-stayed in Paris when there with his mother but without his father, then removed to Munich and then to Vienna, and did so in large part as a rejection of his father’s control over him. 4. While he wrote that he honoured Leopold still as a father, in practice he completely removed himself. 5. Only if Leopold could ‘conclusively prove’ that Mozart’s rejection of subservience, need for independence and resignation from his Salzburg position was wrong would he obey and return. 6. His coarse defecatory and sexual humour both demonstrated his fantasies and was something shared in the circle he was part of. 7. His approach to women was sexual rather than erotic, shown in his letters to Aloysia Weber and the cousin who was probably his first lover. 8. He over-estimated his ability to achieve independence as an artist in Vienna, having earlier over-stated his ability to achieve musical positions elsewhere like Bavaria. 9. He under-estimated how much of his musical competence and confidence put off those who controlled such positions. 10. And while from a distance he tells his father that he is thinking only of music and opera, in fact Mozart was living a sociable life and soon married in the knowledge that his father would dislike his choice of Constanze Weber.

These quotations from Mozart’s letters focus on him as an individual and around his relationship with his father and increasing bid for independence. Although Elias’s wider argument is concerned with the tensions experienced by individuals as a result of social structural factors concerned with the role of the noble courts in relation to musical craftsmanship versus independent artistry, it is notable that Mozart’s letters are not quoted from regarding such matters except by implication regarding his antipathy to the Salzburg Archbishop. Rather it is the two father figures that act as the central motif, seen as propelling his removal from them.

The quotations Elias provides from letters by Leopold Mozart appear in Chapter 6 and the start of Chapter 7. In Chapter 6, the quotations he gives show the hot-house character of the childhood experienced by both Wolfgang Mozart and his sister Nannerl, a few years older and a considerable keyboard player though not a composer in the way her brother quickly showed himself to have outstanding gifts in. Leopold Mozart treats this as a kind of inevitability according to a grand plan he had because these gifts came from God, as well as providing a possible basis for an increase in family fortunes, so while he recognises how much this constrains his children it is still treated as a necessity. Later he also uses the extremely close emotional as well as musical bond that had existed between him and his son when a child to continue to exert control over his conduct. There are just a few quotations from Leopold’s letters in Chapter 7, with the few that appear focusing on practicalities. However, there is also one short quotation that admonishes his son for over-staying in Paris and not earning any money, given as part of a set of quotations showing Mozart’s increasing Independence of mind in relation to his father. There are no further quotations from Leopold Mozart’s letters in the rest of Elias’s book – five more are noted after this, but just as references.

What conclusions might be drawn from this exercise concerning how Elias was using quotations in relation to the idea of an I-perspective?

Clearly this ‘I’ is different from how the term would generally be interpreted at the present time, particularly when used in relation to letters and other sources produced by social subjects themselves like letters, diaries, memoirs and autobiographies. Now and in relation to these kinds of writings, an ‘I’ perspective would most often be taken to mean the world or a small part of it as seen and interpreted by a particular person in how they have produced such data sources, that is, involving a literal ‘I’ who writes letters or diary entries or memoirs.

But this is not how Elias has mobilised the idea of the I-perspective in his book on Mozart, so it would not be fair to judge him negatively for his ‘I-less’ stance. But what was he doing, and how should this be evaluated? Relatively few letters are drawn on, only sixty-two out of the over 600 available to him. While most of the letters Elias references are by Mozart himself, these are not drawn on in a way that explores how he was articulating his own understanding of events and circumstances, but to support and enhance the argument that Elias is making. The way that the fairly few extended quotations are used shows this clearly, for rarely are these concerned with things that Mozart himself stresses, and most often they are things that have been selected by Elias because of their relevance for his unfolding argument. For Elias, then, the I-perspective is in practice treated as locating particular individuals within the social structural context that existed as they went about engaging with others and living their lives, with all the tensions that they had to contend with as a result of wider changes occurring. Mozart as an individual is a case study of this.

Two connected final points.

Elias identifies the propellant point in Mozart’s life as occurring in around 1777 and 1778 when he was in his early 20s (he was born in October 1756), in exiting from his Salzburg post and from over-control by his father, a rupture with these totemic authority figures that took him to Vienna and a desired if eventually failed life as an independent artist. Fuller attention to Mozart’s own letters, however, suggests something more ordinary. In 1771 and in Paris without his father and with his more compliant mother, the adolescent Mozart (then 15) scented independence at the same time that his profound dislike for court hierarchies and their in-built subservience of musicians and confinement of their talents was coalescing, with the years following up to 1778 showing him in cumulative ways exerting increasing independence of mind and behaviour. Yes, he certainly seems to have escaped his father‘s controls in increasingly independent ways, but the sense of anger and resentment that exists with regard to the court system is not apparent. Of course filial piety may have prevented its expression, if it existed, but there is no direct evidence; it seems a product of the kind of stance towards authority and father-figures that Elias had more than how Mozart himself wrote.

The result, Mozart’s arrival in Vienna and passionate need for living as an independent artist, of Elias‘s approach and the one sketched above may be the same. However, the routes that brought him there are seen differently. Elias’s argument is a more dramatic one, of control and rupture with two resented father-figures. Recourse to the letters in detail suggests something more ordinary, an adolescent Mozart growing to adulthood in a context in which he and many others resented old regime subservience and had very different ideas of their own worth. The second point follows, which is that attending in close detail to the letters themselves and exploring their I-perspective in the ‘I’ terms now current indicates some different interpretational routes from those taken by Elias. Consequently exploring the letters in detail is the next task in this ‘Sunday project’ research. This is no small undertaking – the over 600 in English translation that Elias had to reckon with is now, according to the In Mozart’s Words website, more like 1400 family letters.

Last updated: 13 April 2019