Seeing Soweto

For many, the word ‘Soweto’ has a particular set of meanings attached in standing, for the horrors of apartheid; these meanings are in particular attached to photographs from 1976 which have taken on the properties of being what Cornelia Brink calls secular icons. And by ‘many’ here, of course there needs to be recognition that this will be seen differently in South Africa by those who live through or inherited these events, and by those of us elsewhere.

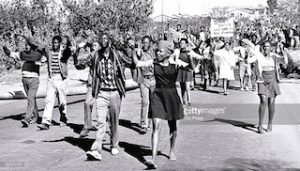

These 1976 photographs are of something which over the last forty years has variously been described as the Soweto protest, riot, massacre and uprising. And some photographs rather than others over this time have become the generally dominant imagery taken to signify the whole, as the huge number of books and other publications on these events indicate. In this regard, consider the sequence of photographs below.

Over time there has been a strange kind of depoliticisation of the political events which happened immediately before the police opened fire, events involving marches and demonstrations and gatherings, and an accompanying emphasis on the victim status of those who died, most of them shot fleeing, many of them children and adolescents. Strange because power and agency herein was assigned to the state and its apparatus in the form of the police and their actions. The police acted, so it goes, while the other people were in response mode: they were shot, they fled, more were shot, many died. For many non-South Africans, it has been only fairly recently that these matters have been returned to a reformed political consciousness, in recognising the fully agentic presence and activities of the black people engaged in political protest on those fateful days in June 1976. This is certainly in no way to diminish the appalling things that happed; indeed the reverse, it is to restore a fuller meaning, that the reponses came from the police et al, while the agency that occasioned their response came from political movement.

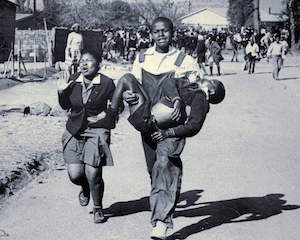

The power of imagery is not total, and nor is it the only thing that underpins how major events of the past are recollected and understood. But it does play a role. And here it is surely notable that one photograph more than any other has come to stand as a metonym for the whole and its meaning. It is the much replicated photograph shown here:

It shows something truly terrible, the raw immediacy of the grief and despair of a sister crying and a friend carrying the dead body of Hector Pietersen, a young boy. It is very powerful in calling to the humanity of the viewer to empathise with all three of the key figures depicted. And its immediacy, that this is the caught moment in which these terrible things happened, is an important part of this. There is something in addition, which plays on symbolism and intertextual referencing. It can be more easily seen by also contemplating another photograph, which has over time overtaken photographs of more general aspects of the killings to become one of the dominant images standing for the 1960 Sharpeville massacre. Ironically, it is not ‘really’ of this, but a fabricated image constructed to make the point, a cardboard child held in the man’s arms. It is nonetheless very powerful.

The imagery that comes to mind is that of the Pieta: a mother, Mary, grieving and holding the draped body of her son, Jesus, under the sign of pity. The dead child held in loving arms by those who grieve, and doing so in that moment of immediacy, is a powerful thing and calls up empathy and human fellow-feeling. It had also become a de-politicised but powerful image, in stripping away Roman occupation and rule, the activities of Governors, military reprisals against dissents, state violence against oppressed people, condensing matters to the human content.

Last updated: 3 February 2017