Randlord bearing gifts

Thinking about this week’s blog and what to write, some idle google searching turned up two wonderful 17th century Dutch paintings that feature a letter used in a symbolic way within the picture’s frame. They were clearly devised as a set, being by the same painter and depicting a letter being written and the letter being read. They are by the Dutch artist Gabriel Metsu [1629-1667] and are now in the collections of the National Gallery of Ireland, and they will be discussed in next week‘s blog. What particularly caught my attention is that they had earlier been owned and donated to the Gallery by Alfred Beit and his wife. But which Alfred Beit, for there has been a number of them.

Alfred Beit the first was the one who made the family wealth. He was one of the so-called ‘Randlords’, the men who became fabulously wealthy through their role in the discovery, commercialisation, and financial wheeling and dealing that occurred around the exploitation, of diamonds and then gold in late 19th century South Africa. They all spent significant time in South Africa, but some of them like Beit returned to Europe and worked in a diamonds/gold or finance context there. Otto was part of the family business too and later accepted a baronetcy. Alfred was a financial wizard and was in large part the source of the enormous wealth of Cecil Rhodes (who referred to him jocularly as ’little Alfred’). Alfred Beit and Rhodes together were a key source of the amalgamation and centralisation of diamond production in Kimberley and its eventual monopoly by De Beers, which company they and their key collaborators controlled. As noted, the paintings themselves will be discussed in next week‘s blog while here some opening thoughts provide brief reflections on which Alfred Beit owned and gifted them to the Gallery and the origins of the wealth that made this possible.

Most of the Randlords were from lowly beginnings and sought and achieved social respectability. Respectability and rising in the social hierarchy is in large part tied up with performance as such, with social display; and Beit’s amassing of an art collection was a significant part of this and an interest he shared with a number of other Randlords, including his younger brother Otto. Alfred’s collection along with Otto’s title were inherited by his nephew and Otto’s son, Alfred Beit the second baronet.

‘Donated by Sir Alfred and Lady Beit’ has a very fine ring to it indicative of charitable giving. But what lies behind this is morally much more dubious.

Alfred Beit the first was ruthless in the financial sense, was at the least complicit in the debacle that was the Jameson Raid which led to the political downfall of Rhodes, and he provided the financial know-how that enabled the so-called Chartered Company, the British South African Company, to operate its policy of invading and subjugating the former Matabeleland (and which eventually became what is now Zimbabwe) in search of yet more minerals discoveries. Ambition, vanity and ruthlessness are powerful motivators, and it is both fascinating and appalling to observe the careers of him and the shabby venal men he associated with as they produced vast wealth through exploiting land, labour and minerals and used this wealth to propel their rise through the social ranks. “Randlords’ conveys the South African connection and the amassing of wealth, but what the term masks is the appalling character of how this was done. And what this in turn indicates is the moral bankruptcy allied with vast resources of the upper class of late 19th and early 20th century European society. Blood on your hands? But there’s money in your pockets, you latter-day Croesus, so join us, accept a baronetcy.

But from Alfred the first, Rhodes’s ‘little Alfred’, rising in the social hierarchy and using his wealth to achieve social respectability and engage in social display, and from him and his brother Otto amassing an art collection, how did these paintings end up in the National Gallery of Ireland?

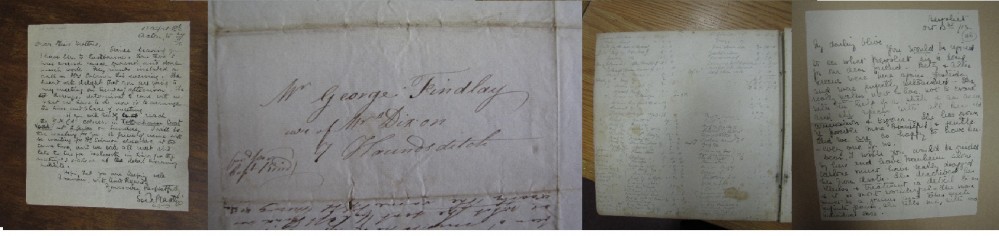

Enter Alfred the second, who inherited his father’s title and also his uncle’s wealth and art collection and was no mean art collector himself. He also became a Conservative Party MP. Alfred Beit the second became one of the Governors of the National Gallery of Ireland, so there is no mystery about his connection with it, while the bequest was less donation and more a transfer made for practical reasons. Beit had bought a rather grand house and land in Ireland with many of his paintings being hung there. Following a number of very violent burglaries and attacks on the then elderly Beits, the art works were transferred to the national collections of Ireland, with another of his donated paintings having a letter as its subject being a magnificent specimen by Vermeer.

How strange it is to think of the quite close connections that exist between the dusty little offices of red-necked diamond-dealers Alfred Beit and Cecil Rhodes in what was originally called New Rush, and the lofty splendours of high Flemish and Dutch art hanging in the galleries of the National Gallery of Ireland. These are now seen by many thousands of people who will mainly remain oblivious of the origins of the wealth and the different kinds of violence that made this possible.

Last updated: 1 March 2019