The death of Elbert Theo Hemming in October 1918

The death of Elbert Hemming in Bulawayo during the flu and pneumonia pandemic of 1918 (or more accurately, 1915 to 1920) has occasioned much thought over the last week. Elbert was the last child of Olive Schreiner‘s older sister Alice, married to Robert Hemming, who was earlier a merchant, then a farmer, and later a founding presence in establishing the South African public library in Johannesburg. Alice died of a family heart condition a short time after Elbert’s birth, in April 1884. She and Robert had many children, most of whom died very young from the same heart condition. After her death, Elbert and his three older surviving siblings Winnie (b1872), Effie (b1876) and Guy (b1880) were then raised by their maternal aunt Hettie Stakesby Lewis, another Schreiner sister.

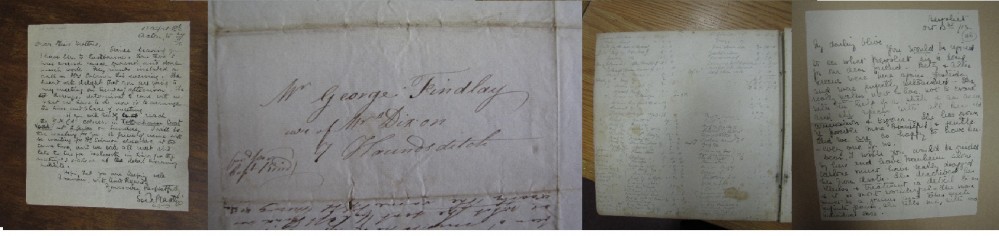

Hemming family members down the generations were great letter writers. This is not in the sense of artistic or other kinds of qualities to their letters, but because of the quantity of them, for they used letters to maintain family bonds over separations of great distance. There are many hundreds of them and they involve five generations of letter-writing. And for a first level analysis of the collection, see the relevant page for WWW’s Schreiner-Hemming Collection work.

The letters by Elbert Hemming start when he was a young boy of four or five, with the last written around six weeks before he died. They are mainly very ordinary ‘duty and keeping in touch‘ letters, from someone close to his family in one sense, but as an adult needing to live at a distance from them. Elbert was not a very interesting man, nor a very pleasant one, for even one of his close friends reprimanded him for being a ‘negrophobe‘ who would hit people working for him. Emotionally damaged, needy and sometimes angry, and unable to settle to anything, his marriage to Norah Johns in 1915 seemed to his family to have stabilised him and he thereafter maintained his job with the railway company in Bulawayo with diligence and the likelihood of advancement. An ordinary white man of his time and type and difficult family circumstance, then.

On 25 October 1918, Elbert’s sister Winnie Hemming wrote to him, saying she had heard he was ill. Winnie like other people had the earlier occurrence of bubonic plague in the Cape area in mind, for talk had it that the plague had broken out again, as many people were dying with black swollen discolourations on their faces and limbs (but which was actually one of the sequelae of the flu virus). Following a holiday visit to his family in Cape Town, on his return on 3 September 1918 Elbert had written to his other sister Effie from Bulawayo, where he lived with Norah on Jameson Street and worked for the railway company, in a letter providing small family news. But Winnie’s 25 October letter in response had crossed with the occurrence of the pandemic. There were no more letters to his sisters from Elbert or Norah.

The next letter Winnie received from Bulawayo was in November and came from someone involved in the local Mission Station who knew Elbert and Norah. It explained that both of them had died from the flu virus and pneumonia, he first in a different part of their house, while she was discovered in the bedroom unconscious and too ill to be told that he had died. She died soon after in a local hospital. There was no Will, and clearly Elbert had died first, on around 19 October 1918. Therefore their sparse possessions, mainly furniture and clothes, were inherited by Norah and then her mother or one of her sisters. And so Elbert – known to his siblings as ‘mother’s little Elbertie’ – fades from the record along with all those many, many millions of people who died during this pandemic, in his case forgotten apart from occasional recollections in family letters and people’s memories.

How to think of Elbert? The Hemming collection of letters acts as a kind of tardis, a time-travelling device in which different people, in this instance Elbert, move through time as the reader plunges a hand and a reading eye into the tardis at this point and that; and so time moves forwards or backwards, the time of their lives. There is the sweet infant, the charming little boy, the fervent Christian attracted to service and a missionary life, the angry adolescent wanting to fight in the South African War, the concerned brother worrying about sibling Guy having a nervous breakdown, the young man unable to settle to any occupation or relationship, the man of ungoverned temper ill-treating those who worked for him, the man who stayed in close albeit distanced touch with his family, the man who loved Norah and took up a regular life, the man of 34 who died alone, his wife in another room also dying.

Last updated: 17 April 2020