Draft Treaty of Vereeniging clauses, May 1902

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2019) ‘Draft Treaty of Vereeniging′ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Treaty/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

(Rev John Daniel Kestell and DE van Velden (1912) The Peace Negotiations Between Boer and Briton in South Africa London: Clay & Sons.)

1. Broad Context

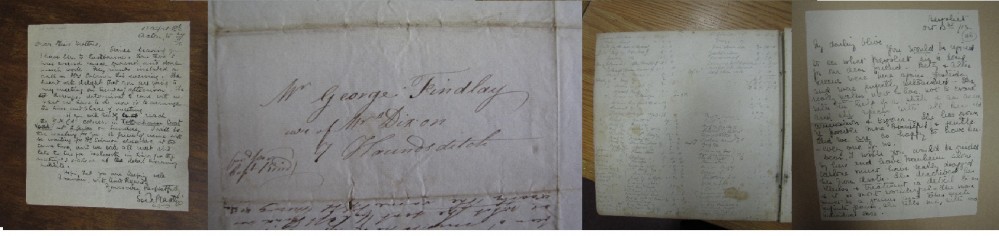

1.1 Shown here is a photograph of a page of some of the draft clauses of the treaty discussed by Boer delegates at the peace conference held in May 1902, and which resulted in the Treaty of Vereeniging. The South African War had started in 1899, largely provoked by Britain and specifically by High Commissioner Alfred Milner, and it was fought for strategic reasons including to gain control of South Africa’s gold as well as diamonds. By early 1902, the British military scorched earth policy had brought about circumstances in which negotiation and implicit surrender was induced by severe Boer fighting incapacity along with lack of ammunition, food and other resources. A peace process then unfolded, culminating in appointed delegates, composed by veld-cornets and military commanders, and the governments of the Boer Republics, along with a British negotiating team, meeting in Vereeniging.

1.2 The photograph of this page of the draft peace treaty is in a book published in both Dutch in 1909 and English in 1912. The English version appeared in significant part to address things going on in the political context and disputes of that date. It pertains, however, to 1902 discussions between Boer delegates as to the peace terms. The secretaries to the delegations were Kestell, a Dutch Reform Church dominee who was the personal minister of ex-President Steyn and acted for the Free State, and Van Velden, who acted on behalf of Transvaal interests and provided ‘stenographic’ or shorthand capabilities. The book that Kestell and Van Velden edited resulted from the shorthand notes and the details, as the Preface explains, were ratified before publication by all the senior Boer figures.

1.3 Broadly, there was a difference of view between the military commander of the British forces, Kitchener, and the political figure of the British High Commissioner in southern Africa, Alfred Milner. Kitchener wanted the war to end speedily and was willing to meet many Boer requirements to facilitate this. Milner had a more punitive approach, and also in his own terms a more principled one concerning widening the franchise post-war to be the same across the former Boer Republics and Natal as in the Cape Colony regarding race considerations. Little of this is evidenced in The Peace Negotiations, however, and what appears is them presenting a united negotiating front before the senior Boer figures.

2. Pre-text

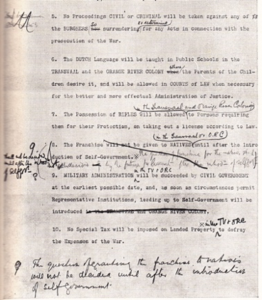

2.1 The original clauses of the draft treaty shown in the photograph reflected perhaps more of Milner’s and the official viewpoint than Kitchener’s, although the eventual treaty significantly accommodated Boer requirements, and it is shown in the re-drafting of the key clauses concerned with responsible government and the ‘Native’ franchise. A sub-committee composed by Kitchener, Alfred Milner, JMB Hertzog and Jan Smuts advised by Sir Richard Solomon, a former Attorney-General in the Cape Colony, met for this re-drafting purpose, preceded by Smuts having a private meeting with Kitchener and Milner. Somewhere along the line a focused editing and revising to change the meaning of the clauses occurred, with Smuts a key presence behind the scenes in this. The edited version is dated a day after this.

2.2 The matters that were at issue are literally writ large on the page shown in the photograph, in particular in the multiple amendments made to some clauses, with clauses 8 and 9 being the key ones regarding governance and race matters. However, the original clauses before their amendment are not provided in the main text of The Peace Negotiations: what appears in the printed text are the reworked clauses, though these are presented as though they are the original versions. The presence of the photograph of the page with clauses 5 to 10 therefore has a revisionary effect – it lets the reader in to part of the process which the main text glosses over, and by doing so it brings Hertzog and Smuts into frame.

2.3 Hertzog, a leading military general, was also a member of the Free State government team and acted as its lawyer, his occupation pre-war. What comes across over many pages of the book is that he was interested in finding a formula of words which would both fit the desire for independence of the former republics and conform to their view of what should happen to ‘the Natives’, and at the same time appear to observe the letter of the treaty as it could be agreed by the British negotiators. ‘Weasel words’ would be a present-day way of describing his approach.

2.4 It is Jan Smuts, however, present as a leading Transvaal general, who was clearly the most influential presence out of all the negotiators on the Boer side, including Louis Botha. Smuts too had been a senior legal officer pre-war, in the Transvaal. ‘Slim Jannie’ became a popular way of characterising him, around his capacity for slightly shady dealings because of his ability to use formal legal language to serve his own covert purposes. As the page of the draft clauses shows, both made an impact in a hands-on way, but especially Smuts, who was clearly the key figure in formulating the revisions shown.

2.5 An interesting question arises as to why the clauses are given in the main text as though the original versions, but then the photograph of the original document with many hand-written amendments appears alongside this and has the effect of undercutting it. This will be considered later in discussing what happened subsequently.

3. The Text

3.1 Another interesting question also arises, concerning what is pre-text and what is the text under consideration, for in the photograph both are ‘there’ and entangled on the page. In addition to the typed original clauses, two different hand-writings appear in the amendments made, which a comparison with writing in other documents shows are by Hertzog and, mainly, by Smuts.

3.2 Two of the sets of amendments in particular will be considered. Clearly editing took place across all the clauses shown on the page in question, but the focus here is on the most important and far-reaching in terms of subsequent consequences.

3.3 Firstly, clause 8, concerned with black people and the franchise, becomes clause 9. Its key sentence is shown and the amendments profoundly change the meaning of the original. The original reads that: ‘The Franchise will not be given to NATIVES until after the Introduction of Self-Government’, meaning that it would be given to them then, as part of the self-government package. The change was from this to: ‘The question of granting the franchise to Natives will not be decided until after the introduction of self-government’, meaning that the Transvaal and Free State would decide whether this would happen after self-government.

3.4 Secondly, it has this implication in quite a strong sense because of the switch-round of clauses, so that the original clause 9 concerned with self-government becomes clause 8. In the original clauses, Britain would decide on the native franchise and grant self-government – specifically, the word ‘given’ is used:

8. The Franchise will not be given to NATIVES until after the Introduction of Self-Government.

9. MILITARY ADMINISTRATION will be succeeded by CIVIL GOVERNMENT at the earliest possible date, and, as soon as circumstances permit Representative Institutions, leading up to Self-Government will be introduced in the TRANSVAAL and ORANGE RIVER COLONY. [Facing p.112]

3.5 In the revised clauses, civil government would occur at the earliest possible date and be ‘succeeded’ by full self-government; and then the Transvaal and Free State would decide on the franchise – specifically, the word ‘decided’ is used:

8. MILITARY ADMINISTRATION in the TRANSVAAL and ORANGE RIVER COLONY will at the earliest possible date be succeeded by CIVIL GOVERNMENT, and, as soon as circumstances permit, Representative Institutions, leading up to Self-Government, will be introduced.

9. The question of granting the Franchise to natives will not be decided until after the Introduction of Self-Government. [P.117]

3.6 Interesting related changes are that in the original clauses, a capital letter is used for the word ‘Natives’ or else it appears entirely in capitals because picked out to have importance along with other key terms. However, the versions in the The Peace Negotiations are always lower-case. In the final version of the Treaty prepared by the British side, the capital letter is restored.

4. Post-text

4.1 When the signing of the Treaty and peace was announced, in many areas people wept and recriminated, demonstrating both the strength of feeling among the Boer population and also the bitter context in which the peace would be conducted. Not long after, Olive Schreiner observed in a letter that hypocrisy characterised what had happened, that the Boer leaders had signed up to a set of things which they had no intention of observing unless they absolutely had to, and that this was also playing out at local levels, in her case in the Hanover area in the Northern Cape.

4.2 Responsible government came as quickly as the Boer leaders had wanted, and more quickly than almost everybody had predicted, propelled by a Liberal election victory in Britain. While Milner might have regretted the ‘Native franchise’ capitulation, as governor of the Transvaal during the initial post-war period he did nothing to inhibit stringent ‘native’ policies. And in subsequent years, and in a major way after Union and full self-government in 1910, there was a steady process of removing political and other rights from the black and coloured populations of South Africa.

5. New Context

5.1 So why was The Peace Negotiations published in English in 1912, why the earlier comment at the start of this discussion that its appearance was in part related to the political context of that date? There is no direct information, but indirectly there were things going on in the period between 1910 and 1912 and these need to be taken into account in considering the question.

5.2 Following Union in 1910, the Louis Botha government included both Smuts and Hertzog, the former as deputy leader holding a key cabinet position, and Hertzog as Attorney-General and Minister of Education. Nationalist feeling and organisation were on the rise, with Hertzog a leading presence in this, indeed as its figurehead. The rankles of the old Free State, that the greatest burdens and suffering of the war had been borne by it and that Botha and Smuts had sold out Boer interests to imperialism and Britain, were involved. This was mixed with the perceived threat from the black and coloured populations and that they might combine against whites, fuelled by the Bambatha uprising of 1908 in Natal and concerns it might spread elsewhere.

5.3 The promotion of related policies around dual language (at that time Dutch as well as English) teaching by Hertzog were the tip of an iceberg of disagreement between him and Botha and Smuts. The Botha government resigned in early 1912, with Botha then immediately invited to form another government, which he did minus Hertzog. But the influence of Hertzog and also of the wide-spread combination of bitterness and nationalist aspiration remained. In 1913 Hertzog broke away from the South Africa Party to form the National Party.

5.4 What of the photograph of the draft clauses and their amendments in this political context? The Peace Negotiations overall is a demonstration of the basic unity of Boer delegates with regards to the British imperial presence, in spite of disagreements over specific points. The photograph of the draft clauses in particular addresses the post-1910 situation because it shows Smuts and Hertzog acting together, and by implication being in agreement with what later became the Hertzog line on race and related political matters. It is clear from his later writings that Kestell saw ensuring publication was important, and by implication as a trusted member of Free State inner circles he was forwarding its interests, with Hertzog’s formation of the National Party also part of such things.

5.5 The account of why publication happened when it did that is given in the Preface to The Peace Negotiations is very vague. It writes that there had been expressions (not specified) of the need for an official publication of the minutes of the negotiations that the Boer delegates engaged in; this would require using the minutes taken by the secretaries; the shorthand by Van Velden was transcribed and was revised by Kestell; and these minutes were read and approved by the leading figures. The Dutch version of the book was published in 1909 and the original preface in Dutch is dated October 1908, in the aftermath of the Bambatha uprising and during the period in which the Constitutional Commission considering what form the union of the four South African states would take was continuing its meetings. The English version was published in London in 1912, in the immediate circumstances sketched out above, and as the strength of nationalist feeling was increasing.

5.6 Outside of government, Hertzog proved perhaps even more of an irritant than when part of it. It is clear, for example, that the lobbying that he and other Free State figures engaged in deliberately targeted the liberal politician who was then-minister of agriculture, Sauer, with this leading to the introduction of the notorious Natives Land Bill, passed as an Act in late 1913.

5.7 Looking at the draft Vereeniging clauses now is a disturbing business. Things might have been different, even significantly so, had Smuts and Hertzog and their pens not been at work. There the original clauses are, plain to see; there are also the revisions, equally so; and through their intrusion on the page, the ball starts to roll down hill. Formal politics and the franchise may not be everything, but they are important. The urge to tippex out the weasel words of these men is very strong.

Last updated: 17 November 2019