Whiteness, now you see it, now…, 1908

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2017) ‘Whiteness, now you see it, now…, 1908’. http://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Whiteness-now-you-see-it-now and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

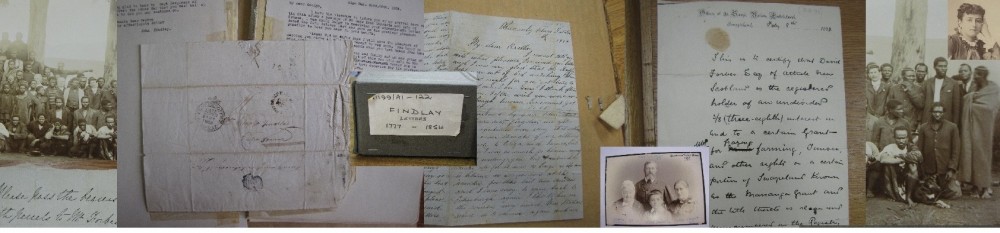

1. Behold two photographs.

2. One is of the Zulu King Dinizulu and liberal campaigner Harriet Colenso, taken in 1908.

3. The other is of the seated Chief Templar Anna Tempo and beside her an unknown fellow Templar of a rank below hers, taken in the late 1890s or early 1900s.

4. These photographs can be taken to show whiteness not least because they show blackness in association with and in relationship with whiteness. Whiteness is revealed and is made plain to see by virtue of its Other, isn’t it?

5. Yes; perhaps; maybe; no; certainly; but; also.

6. There they are, each photograph showing a matched and also unmatched pair, black and white, like figures on a chessboard. In life, relationship matters are ordinarily complicated, although of course this is not to deny that sometimes things are stark, split and violently oppositional. These two photographs, though, look complicated, for neither of them show things and people quite how we might expect them to be, given the time and place each was taken in. In one, the man looks as confident or diffident as the woman stood beside him and both look rather drab in their commonplace clothing. In the other, the two women both look serene or even commanding and are dressed to the nines in the formal clothing of a uniform and regalia. So, just what is it, linked to just who is it, that these two photographs portray?

7. The photographs are the remaining traces of some complicated and momentous, and in some respects contrary, circumstances in South African history and the development of its racial order. Look, see.

8. The first photograph shows King Dinizulu, the last Zulu king of his line, and Harriet Colenso, from a family of radical liberals from Natal (her father was the well-known Bishop Colenso). He is in ‘Western’ clothes rather than traditional Zulu dress, reminding people that at the time of his arrest he had held a government appointment as a kind of super-headman in recognition of his kingly status. She looks respectable and somewhat dowdy; the eye is drawn by Dinizulu and not by her. As its printed caption indicates, the photograph was taken during the 1908 trial of Dinizulu for complicity or more strongly involvement in the Bambatha uprising (1906) in Natal, a fabricated charge designed to remove him from sources of influence and power by discrediting and incarcerating him. The caption also shows that the photograph had been printed and ‘published’ in a public forum; it is not a private one and its caption makes apparent his rank as the heir of Cetwayo.

9. Together with a number of others it is now archived in the papers of Will [WP] Schreiner, former Cape Prime Minister and active politician as well as a high ranking lawyer, who had accepted the brief to defend Dinizulu and spent some months in Greytown doing so. These photographs are all of Dinizulu, his indunas or senior chiefs and advisors, and his wider entourage. Apart from the one shown, they are private photographs rather than public documents. Will, the brother of Olive Schreiner, was both proud to be defending Dinizulu and also perturbed at the political events that had led to Dinizulu being scapegoated. His lawyerly involvement had come about via the Colensos and in particular Harriet Colenso, who attended the trial and gave great support before, during and after it to Dinizulu and his entourage.

10. The photograph is both silent and resonant about these wider matters and also the people immediately involved, the two people shown in it, the person who had been given it and and had treasured and saved it. The wider matters are the destruction of the Zulu kingdom, and through this also the furthering of a racial order in South Africa that moved sometimes incrementally and sometimes, as at back of this photograph, in huge lurches towards the binary system that eventuated as apartheid. Indeed, letters by Olive Schreiner at this time show her to have been well aware that this was the import of responses to the uprising. The photograph, then, represents a point of focus in a vortex of activity and it ‘shows’, unseen in its framing but there in its context of production and consumption, one of those pivotal moments in which the social order can be viewed as having shifted significantly.

11. This first photograph, on one level commonplace in showing just a man and woman, in its own terms has meaning and its disposal of persons stood side-by-side can be seen and thought about, concerning how they are dressed, where they are looking, how they are stood in relation to each other and so on. Its full resonance comes, however, from knowing the context in which it was produced and also in which it was distributed and consumed. The presence of those other white people, the active dissenters from the emergent racial order being established and enforced, also needs to be marked and can be recovered at least to an extent by recognising the importance of not only what is shown but in addition what lies off frame, in context.

12. The second photograph with a seated black woman at a white woman perched at her side? This shows something also momentous, but differently so. It is archived as part of the Schreiner-Hemming collection. With a number of other photographs of the same young then older black woman, both by herself and with children and also at picnics and other holiday occasions, it was once the treasured possession of Ettie Stakesby Lewis, an older sister to both Will Schreiner and Olive Schreiner. It shows, on the left of the photograph, Anna Tempo. Anna was the daughter of freed Mozambique slaves. As a very young woman still in her teens, she had turned up at Ettie’s Cape Town door (asking for a drink of water) in around 1885 when Ettie had become the guardian and adopted mother of her then recently deceased older sister Alice Hemming’s four young children, one tiny baby.

13. Anna, widely known thereafter as Sister Nannie, became a family mainstay as nursemaid to the children and also a key helper to Ettie around Ettie’s role as the Cape Town leader of the Good Templars Christian temperance organisation. The name she was known by was in part the Hemming children’s way of saying Anna, in part it recognised her nursemaid role in relation to the children, and also in part it represented her Christian principles and involvement as a lay sister. Later she became a well-known presence in Cape Town reforming and charitable circles through establishing a number of Homes for young women who were unmarried mothers or otherwise on their uppers, doing so under the name of Sister Nannie. Her connections with the Hemmings, the Schreiners and particularly Ettie Stakesby Lewis were lifelong and mutually close and affectionate, as letters and also other photographs showing her central within family activities as a participant and not in a service role indicate.

14. This photograph shows Anna Tempo seated and in the regalia of a Chief Templar of the Good Templars organisation. Her companion, name unknown, is sat on the arm of Anna’s chair and is wearing the regalia of the rank below, that of a Vice Templar. The Templars were over a long period a force to be reckoned with among the black and particularly the coloured populations of the Cape, although whether such high rank was held by many is not known but perhaps not very likely. Temperance was for many a reasoned response to the use of alcohol dependency to expropriate land and its resources from black populations; and while Christian in origin and motivation, in the Cape it had a highly political aspect to it.

15. The two women are sat close together, the white woman’s arm is loosely draped around Anna’s shoulders, both stare confidently out at us beholding them. A knowledgeable viewer of the photograph – by implication, for whom it was intended – would have been well aware who held the superior rank, if the gleam in her eye had not already given it away. In its own terms, the two women’s pose mimics and undercuts that of a paterfamilias with attendant wife, to interesting effect.

16. Momentous? On one level the photograph is completely commonplace, utterly routine. Two members of an organisation are having a formal photograph taken, that’s all. But it’s not all. This is South Africa and we now look at the photograph through the multiple lenses of its past, minute by minute and event by event all the way from the 1890s to now, with these moments telescoped together under the metronomic force of the word ‘racism’. But while ‘rags to riches’ stories such as Anna’s were not uncommon at the time, when an emergent and rapidly growing black bourgeoisie was in the making, they are not commonly known about now. And one of those Hemming children, Effie, later married a man of visibly mixed-race heritage, Arthur Brown. Such stories should be better known, for Anna and all those like her were proud, resourceful and redoubtable people whose lives in all their rich complexities deserve to be remembered. As too that of the unknown woman with her.

17. And so, what of whiteness? What kind of whiteness is it that the person who now looks at these two photographs sees?

18. At the time the photographs were taken and in the contexts they were taken in, the two black people shown were clearly seen to be of higher status and standing. What difference if any does knowing this make to how these photographs are viewed? Can this innocence and its freedom from knowing ‘what came next’ held in the photographs be reckoned with?

19. Contextual knowledge is important here, for the image does not speak for itself, with the understandings and knowledge of the present standing between us and our attempts to unpack its meaning. This is no simple and one-dimensional matter, for the context was not only of the kindly expression of human fellow-feeling. As it were behind both of these photographs, just off frame, are some terrible things. The slaughter that occurred as a result of the Natal uprising and which destroyed Dinizulu’s life along with it is there. The slavery that led Anna’s parents from Mozambique to South Africa and its after-effects that led her weary and thirsty to Ettie Stakesby Lewis’s door is there. And the accretions that led to the construction of a binary racial order in South Africa did not stop at the point these images were taken, but continued apace after the temporal moments that each of the photographs represent.

20. Many terrible things happened even back then, and also during the many years before it, but in these captured frozen moments of the two photographs there was still hope and possibilities for change. Yes, there was Dinizulu and his fall and the terrible events surrounding the uprising; but yes too, there was Anna Tempo and her rise and achievements and social standing and her great good works. Look, see.

Last updated: 29 December 2017