Where is ‘she’? Her curious absence/presence

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2017) ‘Where is ‘she’? Her curious absence/presence’ Whites Writing Whiteness www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/curiosities/SchreinerCabinet/ and also provide the paragraph number as appropriate if quoting.

1. Isn’t It Curious?

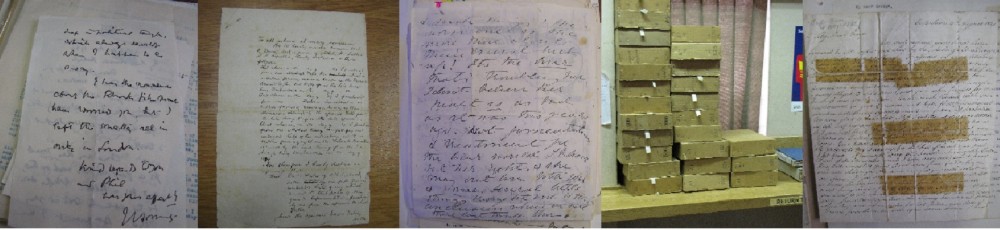

1.1. Olive Schreiner is the letter-writer most represented in the collections worked on as part of the WWW project. In part, this is a product of the fact that WWW grew out of, among other things, the preceding Olive Schreiner Letters Online project. It is in part because around 5000 of her letters are extant. It is also in part because she wrote in a variety of forms in addition to letters, and many remnants of manuscripts or publishers-proofs of her writings survive as well as the published versions. Yes, there are a great many of her letters; and yes, there are also many other writings by her that help flesh out the heterotopic world of her writings, and which show this to be a scriptural economy with particular defining features, including a distinctively constituted epistolarium (Stanley 2004, 2011, 2015; Stanley et al 2012). But – and this is a large but – getting a sense of her remains elusive.

1.2. As a writer of fiction and one of the founding presences of English-language literature in Africa, Olive Schreiner has also been subject – or perhaps object – to a huge amount of scholarly attention over the years which has constituted and reconstituted ‘her’ in a myriad of ways. Much of this is curious, in the sense that it often relies on straightforwardly reading ‘the life’ and ‘the woman’ from the fiction. But also there is a greater curiosity here too, which is that in spite of the mountains of paper produced by Oliver Schreiner herself, there are aspects of her life and her work that remain interpretationally elusive. Although the traces are plentiful, they are never plentiful enough to explain everything that present-day curiosity about the past and Schreiner’s particular place within it want to know.

1.3. Schreiner herself eschewed, indeed she more strongly disliked and rejected, biographical approaches because these place attention on ‘the life’ and ‘the person’, rather than where she thought it should be, which is on ‘the works’ that someone did in the world. As a consequence, my own work in respect of Schreiner has had a similar emphasis to hers. It has attended to her life residually, rather than as a fulcrum or a site for interrogation and enquiry, and focused instead on the manuscripts, the letters and the published works. But of course, the life lived was there and without it having been lived these representational forms could not exist. In addition, along the way a variety of events and material objects have come into view and at times taken on considerable salience in my thinking and writing about the Schreiner epistolarium and the wider scriptural economy this is part of. A number of these objects, these things, are both resonant and also puzzling: they are clearly deeply meaningful, they also remain curious in an ontological sense because raising issues in knowing and understanding ‘the works of Olive Schreiner’ which cannot be resolved easily, or sometimes at all.

1.4. So how to think about this without ‘biographising’ in the way Schreiner rejected? Deborah Lutz’s (2015) The Brontë Cabinet – Three Lives in Nine Objects explores the intertwined lives of the Brontë siblings by reference to the material objects she writes about, which stand for different aspects of their lives, activities and circumstances. Her purposes are strongly biographical and she sees these objects as powerfully raising the realities and facticities of their lives and so helping elide the separations of time etc existing between us and them.

1.5 While not buying into this rather resurrectionalist view of the power of biographical things to conjure up past lives or aspects of them, the broad framework can be helpfully drawn on to think about an Olive Schreiner cabinet of objects which are – and are likely to remain – fundamentally curious, with Janet Hoskins’ (1998) work on biographical objects helpful here. These are objects which focus around ‘the works’ and thrown light ‘as through a glass darkly’ on these.

2. The Curiosities

2.1. The baptismal record: There is a spare entry dated 4 November 1855, recorded in the handwriting of Rev J. Ludorf, of Olive Schreiner’s birth on 24 March that year (access the record here on OSLO). It immediately raises the complex and sometimes tragic family histories which preceded her arrival in the world, with her naming as Olive Emily Albertina containing echoes of the names of three siblings who had died as infants or in early childhood. Having missionary parents was both a plus and minus for the Schreiner children. Olive’s knowledge of both the Old Testament and the New enabled her to out-quote the most vociferously dogmatic of Christians in arguments and she relished the rich source of commanding language she had gained. The narrow punitivenes of her parents was not the only negative aspect of religion, but it was one of them, while her own kindly tolerance combined with firmly stating her own views was a productive later result. Early on, she rejected Christianity and also resisted using the language of God and religion, but later reverted to doing so because it was an idiom which people understood and responded to in relation to ethical and political matters.

2.2 It might be thought that there is little curious here, for missionary parents of course behaved like missionaries, and also at that time parents of many children who died both remembered and look forward through recycling family names. However, these are not the things that are curious. This is rather two other things. One is that in spite of her parents and siblings always calling her Em or Emmie, she developed an attachment to the name of Olive and a point came in adolescence when she insisted on being called this. The other is that at a young age she also became what was then called a freethinker and rejected the Old Testament teachings of both her parents. The death of a younger sister of 18 months of age when she was 9 or so is sometimes seen as the turning point here, propelling her in the direction of a holistic universalism. While doubtless this had a major impact, the curious things relate to a ‘something more’ going on which it is difficult to put a finger on. Certainly there is the sense of a someone from a young age having a strong sense of self, and also repeatedly in her letters and other writings Schreiner relates this to her equally strong urge, also from a very young age, to tell fully articulated stories and later to write these down. How does the urge to tell stories about a world seen in the mind come about? In Schreiner’s case, this was by curious means which have not been satisfactorily pieced together by any commentator to date.

2.3 Photograph of the young Olive: Shown here is the photograph used on the cover of The World’s Great Question, a collection of Schreiner letters focused on her analytical engagement with South Africa edited by myself and Andrea Salter (2014). Schreiner in this is young and confidently stares towards the camera with a look that rejects the dissimulation of an aside glance in favour of meeting full on the gaze of the lens turned upon her. Her look is both enquiringly and somewhat disconcerting.

2.3 Photograph of the young Olive: Shown here is the photograph used on the cover of The World’s Great Question, a collection of Schreiner letters focused on her analytical engagement with South Africa edited by myself and Andrea Salter (2014). Schreiner in this is young and confidently stares towards the camera with a look that rejects the dissimulation of an aside glance in favour of meeting full on the gaze of the lens turned upon her. Her look is both enquiringly and somewhat disconcerting.

2.4 So what might be thought curious about this? There are quite a few surviving photographs of Olive Schreiner, although relatively few of the portrait variety. They are perhaps more misleading than helpful, though, as photographs always are. They are just a few frozen stilted monocrome moments, out of the myriad of moving multi-coloured eventfulnesses of a life lived. They promise much, but what they deliver is modest and full of unintended dissimlitude. The temptation associated with photographs is to read these as though providing a key, to not just seeing, but to better understanding the person portrayed and through this the life they lived. In this way, the works become subsidiary to the life, rather than the life being the medium through which the works come into being.

2.5 The baby’s coffin: A small lead-encased coffin was a constant presence in Schreiner’s life from the death of her day old baby (a daughter, who it seems was never named) in 1895 onwards, although it is seen in a photograph only after Schreiner’s own death (Stanley 2002). As was not unusual in rural South Africa at the time, the coffin was buried on Schreiner land and was moved when Schreiner and her husband removed from place to place, remaining in De Aar with Cronwright-Schreiner when Olive Schreiner left for Europe in late 1913.  It is shown here with the coffins of Olive Schreiner herself and her much loved dog Neta in a photograph taken on the day when all three were moved to the stone sarcophagus on the summit of the Buffels Kop mountain, near Cradock in the Eastern Cape, where they were entombed. A photograph of the cortege on its arrival at the sarcophagus is shown here. Schreiner often movingly mentions her daughter in letters and other writings; and her death was one of the bonds she felt existed between her and WEB DuBois when she read his essay on the death of the first born (his son) in his The Souls of Black Folk (DuBois 1903).

It is shown here with the coffins of Olive Schreiner herself and her much loved dog Neta in a photograph taken on the day when all three were moved to the stone sarcophagus on the summit of the Buffels Kop mountain, near Cradock in the Eastern Cape, where they were entombed. A photograph of the cortege on its arrival at the sarcophagus is shown here. Schreiner often movingly mentions her daughter in letters and other writings; and her death was one of the bonds she felt existed between her and WEB DuBois when she read his essay on the death of the first born (his son) in his The Souls of Black Folk (DuBois 1903).

2.6 Anything curious here? This is not regarding the integration of death in life, as perhaps might be thought, but rather that the entombment of these three on Buffels Kop gives the strong impression of Schreiner wanting to collect together what was most meaningful to her after death. This was both these treasured loved ones and also her immensely powerful attachments to the South African landscape and particularly that of the Eastern Cape. This is because it seems out of character for a person so practical and material in her thinking and analysis to want to do something so resonantly symbolic as being in a tomb looming over a landscape. There are clues as to Schreiner’s deeply felt ideas about the South African landscape in a number of the essays in her Thoughts on South Africa. For some, the Buffels Kop sarcophagous is seen in terms of out-doing or paralleling Cecil Rhodes, also entombed in rock, in his case in the Matopos mountains in Zimbabwe, and who died in 1901. Unfortunately for this contention, Schreiner began to think of being buried in a morgen of land at the top of an Eastern Cape mountain with her daughter in the mid-1890s when she was offered some land and it is probably best thought of in terms of her drawing together those she treasured and loved most of all.

2.7 Tucker’s asthma mixture: Schreiner developed asthma, probably the result of chronic acute allergic rhinitis, in her late teens. Later, she discovered that Tucker’s helped with the symptoms and thereafter never travelled without it (it contained a small amount of cocaine and was vaporised in the nose). It stands for the omnipresence of asthma through her life and her attempts to alleviate its effects in sapping her physical and intellectual energies. It also raises the frequently addictive or otherwise damaging qualities of Victorian medical and quasi-medical treatments, including with Schreiner in her young womanhood being dosed into addiction by treatments given her for asthma by her friend Havelock Ellis, then training to be a doctor. She weaned herself off Ellis’s ministrations, but whether Tucker remained a presence is not known although a point comes when it is no longer mentioned in letters.

2.8 Asthma is no longer the curiosity that it once was and clearly has material and physiological origins. Similarly the Victorian enthusiasm for popular and quack remedies is no longer so curious now it is recognised how much a similar trait characterises our own times. What remains curious is how Olive Schreiner ended up thinking about Havelock Ellis and what comes across in their correspondence is the controlling and quite damaging early relationship he established between them. A point came when she abandoned the remedies he prescribed for her and also left Britain, and while proclaiming how close they remained she always thereafter remained at arm’s length although still valuing his friendship. A very loyal person, it is her actions rather than her words in letters that gives the clue here. But it remains at the level of clues, rather like a jigsaw puzzle for which there are some parts missing, and with the sense that these might be the key to what the picture is of.

2.9 The cloth wrapper in which the manuscript of ‘The Story of an African Farm’ was sent to Britain: The later publication of this novel was an extraordinary event,

not only in the development of English in Africa but also of New Woman writing. It also made Olive Schreiner one of the world’s most famous women. Incredibly resonant in terms of Schreiner’s life and her literary activities, the cloth wrapper also has an especial resonance because the smell of the wood-smoke of the firesides at which she wrote and then wrapped her manuscript preparatory to it being dispatched to Britain is still detectable, conjuring up South Africa as nothing else does quite so powerfully. It is shown in the photograph here.

2.10 But what is curious is that there was actually a significant temporal separation here, measured in many months. Yes a manuscript was dispatched to her friends the Browns for a literary friend of theirs give an opinion on it. However, it was a later version that Schreiner took rounds London publishers after her arrival in Britain over a year later and which was then published by Chapman and Hall. In the intervening period many things happened, with the Browns becoming less important as sources of knowledge and also of strictures about Schreiner’s writing. They provide another example of her loyalty towards friends, too. Thus although Mary Brown expressed her intense dislike of Schreiner’s first novel and distaste regarding its moral and political message, and John Brown was later an oppositional force in the women’s enfranchisement campaigns in South Africa, and Schreiner was well aware of the political and intellectual gulf between her and them, again there just are faint hints in her letters rather than any open acknowledgement of differences. It was not that Schreiner had a problem with acknowledging political and other differences or talking to people about such disagreements. There something more interesting going on about relationships here, but again it is difficult to know exactly what to make of this.

2.11 The meerkats: There are no known photographs of any of Schreiner’s much loved meerkats, but they make their presence felt in many of her letters. Their appearances are sometimes hilariously funny, sometimes tragic, more usually quotidian, but always wrapped around the fabric of her life and affections. They were domesticated and loving, but also remained partly wild and lived much of their lives in the veldt that her Hanover house backed onto. There are letters and other writings that express her thankfulness that she lived at a time in which animals were still part of the world around her, although she foresaw a future time when this would not be so because humankind would have destroyed them. Ibred Sin, Tommy Atkins, ‘Arriet, Emmie, Sancho Panza and the others gave her much joy.

2.12 Surely this might be thought an open and shut matter – Olive Schreiner liked animals. Yes she did, but meerkats are a very particular kind of animal. They are quintessentially African, southern African specifically, and this was part of their attraction for her, as was their fierce loyalty to others of their kind, which meant they would put themselves in danger or even sacrifice themselves to protect those younger or more vulnerable. It is this latter which is curious in the sense of interesting, another part of building up a more rounded picture of why Schreiner became engaged with the ideas and causes that she did perhaps especially regarding her absolute pacifism.

2.13 The immortal green: From photographs, Schreiner seemingly took some trouble with her clothes in young womanhood, while later she had little interest in such things. Her dearly loved nephews and nieces used to tease her about her choice of hats and dresses, which were all about comfort rather than fashion. The ‘immortal green’ was a venerable skirt and jacket which she wore relentlessly even though both unfashionable and battered. The joke ran and ran, and at one point she threatened to dress them up and wear them at a niece’s wedding. There were other cherished items of apparel that are frequently referred to as well. Her favourite hat was a dull affair, deeply unfashionable and like a plain man’s Derby or similar. She was given a Kaross of animal skins by friend’s children and always travelled with it. Before that, there was a cloak she valued and once lost, but successfully got the London police to find it! What comes across is that things were important, but these had to be the right things because invested with meaning through the cherished relationships they signified.

2.14 What could be curious about this? Not every woman aspires to be a fashion-plate, after all. It’s both the humorous recognition of her dowdy appearance and also the resolutely sticking to her guns about dressing as she wanted that comes across strongly. This is a kind of confidence and self-possession, so that while Schreiner sometimes described herself as lacking in confidence in public situations, this seems to have been a matter of speaking on issues she cared deeply about, while at a more everyday level she had little hesitation in conducting herself she wanted. In post-war London, the very incapacitated Olive Schreiner described herself in a letter to Jan Smuts as an old woman lying on the sofa but who thought she could outthink men of affairs like him. She meant it, shabby and ill-dressed though she was. And she was right.

2.15 The future: A Schreiner cabinet of curiosities would not be complete without letters, and the first choice of a letter is a powerful one of 9 April 1909 written to her dearly loved brother Will, a lawyer-politician who had earlier been Prime Minister of the Cape and was at that point a senior member of the South African political elite (access the letter, on OSLO, here). In it, she writes about a debate in the Cape parliament about Union of the white settler states in which erstwhile liberals reneged on their political principles with regards to race matters. She had been sitting in the gallery of the parliament building next to Dr Abduraman, leader of a political pressure group on race issues, and had watched his face as he looked at them. She comments to Will that fate and the future were looking down on the white politicians concerned, with the strong implication that in that future-to-come they would not be there.

2.16 Deeply curious! But this is not that Schreiner or Abduraman were there together or might have agreed about the implications of what was happening. The curiosity is rather that a future focus such as Schreiner’s is rare among social theorists, who tend to look to the past as it informs the present, or vice versa. Throughout both her formal writings and also her letter-writing, Schreiner always attends to the ramifications of the present moment and how it will play out in the future, including the far future that much of her writing invokes.

2.17 The last chance: Another powerful letter needs to be included in a cabinet of Schreiner objects. This is her letter to the politician Jan Smuts, written on 19 October 1920 in the midst of political upheaval and with Schreiner’s gaze firmly on worsening racial hierarchies and injustices. (access the letter here) In this she writes that Smuts, as the then Prime Minister of South Africa, was having his last chance to conduct political life with some vestige of ethical probity towards the black majority The strong implication of her letter is that in spite of his great gifts he would fall morally and politically short, as he always had done from since she first met him back in the 1890s. He did, and if any one single individual can be seen to be responsible for the segregated and later apartheid character of the South African state then it has to be Smuts, who from the days of the 1902 Treaty of Vereenigen on at crucial junctures steered things in that direction.

2.18 As with Havelock Ellis and with Mary and John Brown, what did Olive Schreiner really think of Jan Smuts? The answer is surely a number of things, some of them quite contradictory, and this is par for the course for a friendship between two politically involved, clever and opinionated people with passionately held political and other convictions, including diametrically opposed ones on race and labour matters. What is curious here is that Schreiner persisted for so long in communicating with Smuts and endeavouring to shift his ideas and political policies. By 1920, she must have known there was no hope at all of any significant shifts or indeed minor ones, and so this is perhaps yet another example of her not giving up on people she had once cared about. The alternative is that she did so in the voice of conscience, a needling kind of voice reminding him that there was a right thing to do but he wasn’t doing it.

2.19 Old, battered and so to say with her back against the wall: This is how Schreiner’s estranged husband described how she looked in a passport photograph she had taken in mid-1920 preparatory to returning to South Africa, where she would die on 10 December that year (Stanley 2002). The photograph is shown here. She was 65 when it was taken, but in the photograph looks considerably older, battered indeed, due to the onslaught not only of long-term asthma but also the congenital heart condition she and nearly all her siblings had inherited from their father Gottlob Schreiner. In this photograph, she stares steadfastly at the lens gazing at her; she looks indomitable as well as battered. It is in many ways a sad photograph, a sad sight to see. But it represents something more than this as well. She resolutely stands, staring back at the gaze cast upon her. Here for the duration, making the best of things.

2.20 What is curious about this can also be detected in the discussions of other objects above, and this is the urge to make sense of and to find meaning in the objects chosen, to discern a pattern into which they fit. Insofar as this is the underpinning motif for the discussion here, it is a pattern articulated around research issues and questions and it bears a complex and removed – but how removed, that is the question? – relationship to the kinds of issues and questions that concerned Olive Schreiner herself.

3. ‘She’, Even More Curious…

3.1 Not a conclusion but simply a statement. These ten objects are resonant ones, Schreiner writes about and comments about all of them at different points in her letters and elsewhere, and they are all interesting. However, what they do not do is what most commentators on lives of the past would like, which is to get closer to understanding the biographical presence, the life and person of the writer. ‘She’ remains an absent presence. What the discussion here has suggested is that these things raise questions that remain unanswered about what all of them mean and the limits imposed on our understandings of them.

References

Janet Hoskins (1998) Biographical Objects: How Things Tell the Story of People’s Lives Routledge: London.

Deborah Lutz (2015) The Brontë Cabinet – Three Lives in Nine Objects New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Liz Stanley (2015) “The scriptural economy, the Forbes figuration and the racial order” Sociology 49:5, 837-52.

— (2011) “The Epistolary Gift: The Editorial Third Party, Counter-Epistolaria: Rethinking the Epistolarium” Life Writing 8:3, pp.137-54.

— (2004) “The epistolarium: on theorising letters and correspondences” Auto/Biography 12, pp. 216-50.

— (2002) “Mourning becomes…: the work of feminism in the spaces between lives lived and lives written” Women’s Studies International Forum 25, pp.1-17.

Liz Stanley, Andrea Salter & Helen Dampier (2012) “The epistolary pact, letterness and the Schreiner epistolarium” a/b: Auto/Biographical Studies 27: pp.262-93.

Liz Stanley and Andrea Salter (eds, 2014) The World’s Great Question: Olive Schreiner’s South African Letters 1889-1920 Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society.

Last updated: 23 December 2017