A874 Parkinson Accession, Pietermaritzburg Archive Depot

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2018) ‘Collections: Parkinson Family’ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Collections/Collections-Portal/Parkinson-Family-Letters-Collection and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

1. The Collection

1.1 The Parkinson Accession (A874) is a very large family collection with contents spanning the period from 1852 to 1949. The collection is located in the Pietermaritzburg Archive Depot.

1.2 The Parkinsons were a farming family which also had wider business and commercial interests. The farm Shafton Grange, at Lions River in the Karkloof Valley near Howick, was their principal property. They were related to the Methleys by marriage, and they became part of the Natal Midlands gentry.

1.3 There is a useful although rather schematic Inventory available in the Archive itself, which overviews the broad shape of the collection. However, this lacks detail and does not really convey the large scale and significant scope of content, which are considerable.

1.4 The collection is configured with sub-divisions organised around particular family members and their remaining papers, which include letters and also for most of them diaries as well, and also some ancillary papers such as press cuttings and religious texts.

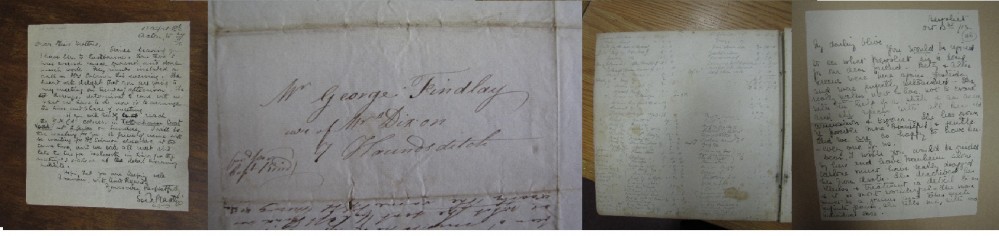

1.5 This structure has the virtue of being a very clear one. At the same time, dividing up all the papers in this segmented way gives an over-emphasis to family members living parallel lives, and an under-emphasis to them sharing in a collective enterprise, that is, the wider set of farming, business, commercial and also social concerns shared in common. For instance, many of the letters are part of correspondences between family members, but are divided up under the name of the letter-writers rather than kept together with all the letters of family members in a time-series of exchanges (such as exists for the Forbes and Findlay Family collections, discussed elsewhere on WWW pages).

2. The Parkinson Family in the Karkloof Area

2.1 Edwin Parkinson (1819-1895) and Mary Stocks Parkinson nee Methley (1829-?1902) arrived in Natal in 1851. Rather than going to one of the more usual coastal areas of settlement, they took up the land that became Shafton Grange in the Lions River area (north of Pietermaritzburg and near Howick) that had been originally purchased by James Erasmus Methley, a cousin of Mary Parkinson and a friend of Edwin Parkinson. One of the Methleys’ key properties, Shafton, abutted Shafton Grange while the other, Newstead, was a distance away, with the two families remaining close over the generations. Shafton Grange is frequently referred to in the Parkinson papers as the Grange, presumably to distinguish it from the nearby Methley Shafton property.

2.2 Strictly speaking neither the Methleys nor the Parkinsons were Natal settlers, for although they arrived on Byrne emigration scheme ships they did so as paying cabin passengers. Also through James Methley, who had earlier spent a significant period in Natal, they had an already existing connection with some well-connected figures in the settler community of the day, in particular Rev James Archbell and the LMS missionary Rev Thomas Hodgson, with the latter being the father of Methley’s wife Isabella.

2.3 There were other Byrne and related settlers in the Howick/Karkloof district, including William Strapp, farming at St John’s, Richard Lawton at Knollebank, the family of William Frederic Morton at Fountaindale and The Start, Revd John Methley at Singleton as well as the Parkinsons at Shafton Grange; George Trotter at Yarrow, and two of the four sons of Ann Shaw at Talavera. And not far away on the Umgeni, William McKenzie was resident at Cramond. A large amount of land in the Karkloof area by the 1850s – some 59 000 acres – belonged to Wesleyan ministers, with Rev James Archbell present in Natal from 1842, and who owned Stocklands, Oatlands and Woodlands. The Parkinsons, then, were part of a small but growing settler community of a distinctly gentry character, farming on large estates and although engaged in a range of business and commercial activities, their core interest were and remained farming.

2.4 The Parkinsons and their children are as follows:

Edwin Parkinson 1819 – 1895, m. Mary

Mary Stocks Methley 1829 – ?1902, m. Edwin

Mary 1852 – 1894, ?

Francis [Fanny] 1852 – 1926, m. 1880 Robert Bucknall

Edwin [Eddy] Blundell 1856 – 1932, m. Ethel

Arthur Samuel 1858 – 1908, ?

Amy Hannah 1861 – 1934, –

Kate Methley 1863 – 1956, –

Emily Marian 1868 – 1962, m. Hutchinson

3. Collection organisation

3.1 The organisation of the collection and thus also its Inventory follows this family structure, as noted earlier, although it is mediated by the relatively sparse materials extant for some family members.

3.2 There are 97 boxes in the collection, organised in a single formulaic way as follows:

Edwin Parkinson [boxes 1-21], Correspondence, Diaries, Financial, Miscellaneous

Mary Stocks Parkinson [box 22], Correspondence, Miscellaneous

Arthur Samuel Parkinson [boxes 23– 44], Correspondence, Financial, Miscellaneous, Diaries

Amy Hannah Parkinson [boxes 45 – 67], Correspondence, Financial, Miscellaneous, Diaries

Kate Methley Parkinson [boxes 68– 81], Correspondence, Diary, Financial, Miscellaneous

Edwin [Eddy] Blundell Parkinson [box 82], Correspondence

E Parkinson [box 82, also re Eddy], Correspondence

Fannie Bucknall nee Parkinson [box 82], Correspondence

Emily Marion Hutchinson nee Parkinson [box 82], Correspondence

Miscellaneous [boxes 83–97], Photographs, pamphlets, brochures, sheet music, press cuttings etc

4. Family Business

4.1 Central to the family business was running the farm estate at the Grange, with additional property near Lidgetton later farmed by Eddy Parkinson and his wife Ethel and by her alone after his death in 1932, and also some other land in the Karkloof area of the Midlands.

4.2 The letters especially in combination with the diaries of those family members most closely involved in farming activities convey the diversity of activities involved rather than any reliance on single crops or activities. Thus crops were frequently switched to suit market circumstances, and also involved sheep farming for wool as well as meat and tallow, and also stock breeding as well as raising stock for dairy products and for slaughter. Fruit growing was also involved although not on the scale and with the degree of success achieved by the development of the early ripening Methley plum.

4.3 The Lions River and Karkloof area of the Natal Midlands is inland, and transport riding was a key activity of the Parkinson sons, being involved with other young men (many of whom they were connected with by marriage) in providing inland transportation of goods and produce both to and from Pietermaritzburg, Durban and other coastal areas and ports. There was no railway and before advent of motorised transportation this was the only means of distribution other than by oxcart. As well as a service, transport riding was also a means of raising ready cash, and was a useful addition to the family business portfolio.

4.4 With regards to settler farming and farm-estates at this time, it is a mistake to assume a supposedly conventional gender division of labour, in which farming and its labour management was men’s work, with the household reserved for women. For many, it was simply not like that. Certainly after their father Edwin’s death in 1895 (and the signs are, before this as well), sisters Amy and Kate had established a division of labour in running the Grange, with Amy overseeing (and as her diaries show, doing this in a very hands-on way) its farming and commercial interests and Kate running its family, household and social aspects. Their brothers and to a lesser extent the other sisters remained involved, with for instance Arthur Parkinson dividing his time between employment as a stock inspector and stock breeding at the Grange, and Eddy Parkinson with his wife Ethel farming the property at Lidgetton. In the latter instance, Ethel ran the farm after her husband died and there was no consideration that she might not do so on her own.

4.5 The Parkinsons can be aptly described as gentry. This is both in terms of their position in the settler hierarchy and economic fabric, and also because they constituted part of a distinct fracture of the white population which was settled as gentry with a distinctive rural and estate-based way of life, rather than being aspirant professionals or large-scale entrepreneurs. They are consequently interestingly compared with the Forbes on one hand, and the Findlays on the other, both also of the ‘middling sort’ and varieties of gentry. The Forbes family was by comparison entrepreneurial at a higher level, combining farming cash crops for an international as well as national market on their farm-estate at Athole, transport riding, sheep and stock farming, horse-breeding of high quality Arab stallions, diamonds and gold prospecting and mining, business company formation and company directorships and more. The Findlay family was more diverse in economic terms, starting in South Africa as shopkeepers and traders, but with the main branch of the family later moving into a high-level of professional activity in the law, producing a number of leading attorneys and considerable involvement in the civic and public life of Pretoria.

5. The Letters and Diaries

5.1 In general, the content of letters in the Parkinson collection cannot be easily divided into distinct categories such s’family’, ‘business’, ‘personal’ and so on. As is generally true of letters in the South African collections that WWW has investigated, business life, family life, personal life and also to considerable extent political life overlapped each other and are represented in this way in people’s letters, which slide from one kind of topic to another within the same framework. Relationships were complicated in a settler context in which there was no marked degree of divisions of labour and where people necessarily combined different kinds of activities in order to stay afloat or to succeed in economic and practical terms.

5.2 This can be to seem by taking any one of the sets of letters in the collection, that is perhaps particularly marked regarding the letters of Edwin Parkinson and his daughter Amy, as the family members most involved in a first-hand way in all the public activities associated with farming as well as those occurring on the Grange estate in itself. However, an interesting comparison can be made here with various of the letters and other papers of Arthur Parkinson regarding his permanent employment from 1908 on as a stock inspector (having worked in this capacity on a part-time basis previously). These are largely focused on the practical matters in hand in written exchanges between him and owners of stock with regards to the dipping and transportation or confinement or slaughter of these, and in this sense they do not have the ‘mixed’ content of many other letters in the collection.

5.3 In addition, letters exchanged between family members have more social and relationship content, as comparing them with Forbes letters shows. This suggests that the farming and business aspects were mainly expressed and discussed in letters with people outside of the family circle, because they could be dealt with on a daily basis between family members.

5.4 None of the Parkinson diaries are of a ‘storm and strang’ kind, none of them are ‘personal’, and while strictly speaking only Edwin’s then Amy’s are ‘farm diaries’ in the South African sense of the term, in fact all the others share similar characteristics. They focus on externalities, and in particular record daily activities together with factual information concerning the farming context. And as with farming diaries more generally, they have an implicit external addressee because they were required to record information to be returned to government sources and might also be required to be produced in a range of legal situations pertaining to, for instance, the occurrence of locust plagues and the movement of stock when there were outbreaks of rinderpest or lung disease. As a result, they provide much valuable information about quotidian everyday relationships with black people as sources of both permanent and temporary labour, and are an interesting and at times illuminating addition to Parkinson letter-writing.

5.5 There are some broad patterns of observable in the changing use of ethnic and race terms over time suggested by the Parkinson letters. In earlier letters, the word ‘Kaffir’ is used as a general term for all black people and retains a sense of ethnicity rather than being solely a racial category. Later in these Natal-based letters, the general term becomes the ubiquitous use of the much more diminishing ‘Boy’ of any male who was black, being a term which has no ethnic connotations but is an implied evaluative descriptor. In the later part of the period covered by the letters after approximately 1900, the word Coolie comes into usage. There were Chinese workers in the area before this period, and there will also Indian indentured labourers present, with practical use using the word as a coverall to refer to members of both ethnic groups.

5.6 However, alongside general categories, there is considerable use of personal names to refer to people who are, because of the particular names they have, implicitly not white. Mainly, single names are used in this context, and there is no addition of a family or other category of belonging, another indication that the people concerned are not white, for white people outside of the family circle are either referred to with a title and family name, or with a personal and family name. There is no sense that single names are used for deliberately negative or diminishing purpose; rather this is the effect of the implicit racial hierarchy that exists and is taken for granted, and which gives rise to such naming practices.

Last updated: 1 January 2018