Where our country is going: Goldberg to Botha, 13 February 1985

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2021) ‘Where our country is going, 13 February 1985’ https://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/traces/where-our-country-is-going-goldberg-to-botha-13-february-1985/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate if quoting.

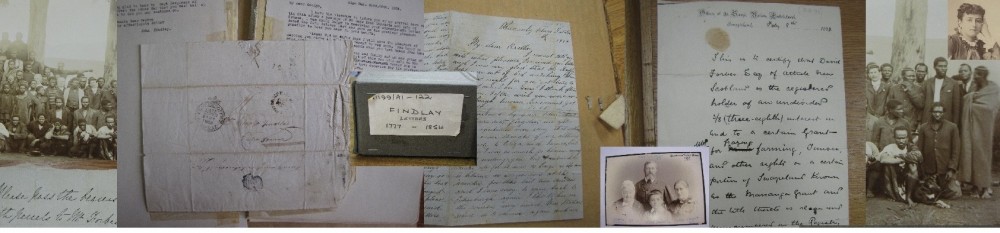

1. Denis Goldberg was one of the Rivonia trialists, together with Nelson Mandela and Albert Sisulu. He was in prison for some 22 years and released in 1985. The website of the charity he founded, shown above, has much interesting information and discussion on it. It repays an attentive visit for anyone interested in the times, the places and the people who made change in South Africa possible.

2. The screenshot opening this Trace comes from the website and it shows the start of a letter, a statement, a demand, a manifesto… It is a transcript of an original document, and Goldberg himself refers to it fairly near its end as a memorandum. It could be classified in various ways, and its entire text will be found at the end of this discussion for present readers to peruse.

3. The context was that release had been offered to some political prisoners – at a price. Change and the possibility of yet more change was in the air. Things were on the move. This document was Goldberg’s response to such an overture to himself, a response which appears under his name and also as though a personal letter from named person addressed to another. But clearly he is writing on behalf of a collectivity and addressing the document to another collectivity, which Botha headed as President of South Africa. Goldberg, in a Pretoria prison, comments that he was not allowed to communicate with other key people, the ANC leadership on Robben Island in particular. But at a guess there were ways and means by which some sense of what was happening got through even if not specifics.

4. The document is headed as though it is a letter, for there is an address and a date and so on; and the document ends as though it is a letter, with a formal sign-off and the typed signature of the writer. But its content is a different order of thing, hovering on the borders between being a letter and not being a letter, not being a letter but being not entirely something else, for although Goldberg calls it a memorandum, it also has these features of letterness to it.

5. Thinking about its content reveals a number of interesting aspects which throw light on what kind of document it is.

6. The letter/memorandum starts with a lengthy statement of the points being made, and having done this it then explains that it was a kind of summary and some of the points would will be dealt with in what is to follow in more detail. It is a document that the reader/addressee is to learn from, through having the main points of the argument put twice in slightly different ways. In effect, Goldberg is acting as an instructor, in pointing out the consequences of various actions or inactions to Botha and the wider political audience that stood behind him. And it is worth noting that he also disavowals making a personal response, he is concerned instead with “where our country is going,“ not his own individual position.

7. This sense of Goldberg as an instructor and also as the person with the moral authority comes across in addition in the tone of the document, for there is no sense at all that he is a supplicant, a prisoner, writing to a person who has ultimate authority over his treatment and how much of his sentence he would serve. Goldberg is the person with authority, he is the person who explains the pros and cons, the consequences, of political activities and decisions. He also points out the massive contradictions of the political viewpoint that Botha stands for, that it makes more likely the very thing that it fears, it makes more likely bloodshed rather than less. And Goldberg also points out what democracy actually means and entails, and that it is actually the ANC and others who represent it, not the apartheid government.

8. Moral authority as well as political authority belongs to the writer, the excellent Denis Goldberg.

9. And what of whiteness? The first thing to observe is that Denis Goldberg was white and in a very high position within the ANC opposition to apartheid, like others. This was a time when the movement had the sense of a rainbow nation in the making. The second thing to observe is that these were hard times indeed, but there was the promise and the possibility. They wouldn’t get much truck now.

D.T. Goldberg (2/82)

Pretoria Security Prison

13 February 1985

The State President

Mr. P. W. Botha

Dear Sir,

My response to your offer of release is concerned more with where our country is going than with my personal position.

The key element in the growing political crisis in our country is the representation of the black seventy per cent of our people in the central organs of government.

The peaceful solution of political problems requires the creation of the conditions in which normal peaceful politics can be freely and meaningfully practised.

It is clear that any credible moves to resolve key political issues must involve the African National Congress, and its presently imprisoned leadership.

The issue of the involvement of the ANC should not be reduced to a question of “face”, of who backs down first. Unless we can by-pass this stance we cannot even begin to resolve the main problem of representation. There must therefore be mutual undertakings, for without them we are no nearer the peaceful resolution of the central issue of our time.

Already I can see a deadlock in the making when there appeared to be a possibility of movement. In the belief that it is necessary to maintain the momentum I suggest that an “undertaking to participate in normal peaceful politics which can be freely and meaningfully practised,” should be acceptable to you.

As I see it, your acceptance of this undertaking would signify your acceptance of its terms. The mutual undertaking and acceptance would help to create the required conditions, and would go a long way to achieving a political settlement of our country’s political problems.

I call upon you to release the fine people with whom I was tried in the Rivonia Trial and other political prisoners, and to legalise the African National Congress.

With these things achieved there would be a good prospect of attaining a peaceful settlement embodying the guarantees of the Freedom Charter for the rights of individuals, for national groups and for cultural groups in a United Democratic Republic of South Africa.

In what follows I have expanded on the foregoing summary of my approach.

Those of us in prison for political offences involving armed struggle, especially those tried with me in the Rivonia Trial, have a passionate commitment to democracy. That is why we are in prison. We cannot accept a system which provides some form of democracy for the white minority, together with a complete denial of democratic rights to the majority of South Africans.

It was the determination of the White State to close every avenue of development towards a real democracy, by cracking down on peacefully expressed demands and protests that led to the decision to embark on a course of armed struggle. That decision was not lightly taken. It was a choice of last resort made long after there was a widespread demand by black people for protection against the armed might of the state.

Where there is no democracy and no channel for the political demand for democracy it is the duty of democrats to participate in the struggle for democracy.

As a white citizen of South Africa I could see that whites too were becoming less free, despite their enfranchisement.

Freedom is truly indivisible.

The price of freedom for whites is the acknowledgement and implementation of the right of all the people of our country to enjoy the same democratic rights. Failing that, whites will find themselves ever less free as the struggle for a just and democratic South Africa is intensified.

The South Africa we wish to see is one in which our people can live together in peace and friendship; a South Africa in which the creative potential of our marvellously diverse peoples can be liberated for the material and cultural enrichment of us all.

We know that despite their diverse cultural backgrounds, all the people in our country (i.e. the pre-balkanised territory of South Africa) want essentially the same things: to earn a living, to be together in their families, to see their children well fed and educated, to laugh a little…… Skin colour, in this fundamental sense, is irrelevant to our hopes and aspirations.

Does it matter that one cultural tradition prescribes stywe pap and tjops for enjoyment, while another specifies putu and the same cut of nyama, or that yet another prescribes yoghurt instead of amasi? [NOTE: Afrikaans: stywe pap = hard maize meal porridge or polenta = Xhosa: putu; tjops = chops; Xhosa: Nyama = meat]

I notice that in your address of 31 January, you did not refer to political rights for blacks, while in your address on the opening of parliament you did so. From memory of newspaper reports you said that possession of property rights did not confer political rights. That could be a very democratic proposition as it correctly excludes a property qualification to the right of franchise.

I suspect, however, that your proposition was profoundly undemocratic in that you were denying to black people the democratic rights which constitute the notion of citizenship.

Mr Heunis (Minister of Constitutional Development) has recently said (again from memory) that your Cabinet constitutional committee has come to the conclusion that the exercise of political rights by what you call “urban blacks” through the euphemistically termed “homelands” is unacceptable to them. “Urban blacks” have no connection with the “homelands”. Mr Heunis went on to say that your government accepted this conclusion, but nevertheless insisted that the political links to the “homelands” be retained. (This despite the clear rejection of the whole concept of the “homelands” as pseudo-independent States by black people.)

This is a prescriptive approach. It is not a democratic approach which takes into account the acknowledged standpoint of black people.

This gets to the heart of the matter. In your perpetual quest for cast- iron guarantees for the protection of the position of whites, and especially of Afrikaners, you are defeating your own purposes by denying democratic political rights to blacks.

The ever lengthening delays in the implementation of a truly democratic system in our country (a State which will nevertheless come into being) results in growing frustration and anger. I fear these feelings may lead to the very dangers for whites which you are concerned to avoid.

I fear that if continued any longer the precedents you are setting in the treatment of whole groups of people, of black people in particular, and of individuals, are dangerous. Your precedents will make it more difficult for we who want to build our country for all our people, to prevent some people from invoking your precedents.

It is my firm conviction that the only guarantee you have for the secure future of whites is in a South Africa in which everyone will have full democratic rights backed by the long-held commitment of the African National Congress to uphold those rights.

The ANC has always held that people are of equal worth regardless of the colour of their skins. Precisely for that reason it was, and is, possible for whites to give their wholehearted commitment to the ANC, as I did.

I am convinced that the Freedom Charter, which is written into the constitution of the ANC, provides a solution in principle to the problems of our country. The guarantees it provides for the liberty of individuals, for national groups and cultural groups, are the basis for a peaceful South Africa.

The Freedom Charter is insistent that the diversity of cultural and language traditions (which must, and does, include Afrikaans) must be respected and their development encouraged.

We have, as you remarked in your address, vast resources of every kind. You managed, however, to omit the greatest resource: the vast creative energies of our people which can be released only if they are free. Of necessity this requires the freedom to participate in all the central government organs of the State, for then they will have protection against the structural violence of our society and the arbitrary acts of government which drive black people off the land, out of jobs, and into barren lands of gross malnutrition. Their potential is stifled. Poverty-stricken people cannot fulfil the role to which you assign them: that of a market!

It will take generations to realise the full potential of the free people of a truly democratic South Africa. We need to make a start.

By redeploying the human, material, and financial resources at present used to prevent people from developing, we could make a significant start to the building of a new South Africa.

We envisage a South Africa which can meet the material and spiritual needs of our more than 30 million people within the original territory of South Africa.

Let us stop using the armed forces and police, and the civil service, to bolster a way of life which we all know cannot survive. “Adapt or die!” you said. Let us use the resources wasted by these State organs to build anew.

I have told you of our commitment to democracy. You have on occasion asserted your belief in a democratic society. Let us put our beliefs to the test. Let us have a real national convention to draw up a constitution which includes all the people of our country. The informal toy forum you have proposed is not equal to any serious task. Not the least reason is that the participants in it will be your nominees, not elected delegates of all our people.

Let us call an election of delegates to a constituent assembly, with all adult persons having the right to vote for delegates.

It is clear from recent events, and from commentaries in the Press, both Afrikaans and English, that the credibility of any political moves to solve our problems requires the involvement of the African National Congress, and therefore the release of political prisoners, to participate freely in the political process.

In such circumstances I believe you would not have to fear the continuation of armed struggle. I would willingly participate in a non-violent political process such as I have outlined. (I believe that my comrades in Pollsmoor Prison and on the Island would also participate, but I have been refused permission to consult them on this memorandum.)

I have complete confidence in the political judgment of the people of South Africa, provided that their opinions can be freely expressed in a genuinely free and fair election.

Let us do this now before our infrastructure is destroyed; before our economy is damaged; before untold billions are wasted on a futile, Canute-like, attempt to stop an irresistible tide. Let us build on what has already been built, not destroy it.

Let us do this now before even more lives are unnecessarily lost. We surely cannot allow our children to be shot down, nor people to be removed, especially if forcefully removed, nor detainees to die in detention, nor families to be split by the migrant labour system, in the name of policies which you now concede to have been wrong.

Let us make a start.

Let us take a bold leap into the future.

The choice is in your hands. You hold the keys to our prisons. When you have opened the doors and we are free again, the choice will be ours. The fact of the matter is that should anyone, ex-prisoner or not, contravene your laws on violent political action you have the power to impose the sanctions your laws provide.

Our preference has always been for normal peaceful politics. The special circumstances described earlier forced us away from that path. The crux is surely to create the conditions in which normal peaceful politics can be freely and meaningfully practised. We should not allow this to become a question of “face”; of who backs down first. Unless there are mutual undertakings we cannot even begin to address the central political problems to find a peaceful settlement of them.

If we are to maintain the momentum of the process it seems to me that a mutual giving and acceptance of an “undertaking to participate in normal peaceful politics which can be freely and meaningfully practised” should be acceptable to you.

I call upon you, in the interests of our country, in the interest of the great task ahead of us, to release the fine people with whom I was tried in the Rivonia Trial, and other political prisoners, and to legalize the African National Congress.

The great task I refer to is to work towards the political settlement of the problems of our country. We must achieve that political transformation from a system which separates our people and peoples from each other in great strife and growing bitterness, to a system which embodies the guarantees of the Freedom Charter for the rights of all individuals, for all national groups, and for all cultural groups, and in which all our people constitute a United Democratic Republic of South Africa.

Yours faithfully

Signed: D. T. Goldberg

Last updated: 17 December 2021