Sweetest of young persons, 24 March 1907

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2020) ‘Sweetest of young persons, 24 March 1907 ′ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Sweetest/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

Sunday night[1]

Sweetest of young persons.[2]

I enclose a bit of a letter I’ve just got from Con Lytton.[3] You’ll simply worship Mrs Earle.[4] You must go to see her. She’s about 75 with lovely snow white hair – & as young in heart & her sympathy with the young as if she were 20.

I know you the little mothie[5] are having a lovely time Give my love to Nell & her charming little boy.[6] I shall never forget that dear child though I saw him only for a few minutes

It’s Saturday night. Cron[7] went off at 8 this morning to play golf & spend the day with his mother & brother, & tonight he is sleeping at Bergvliet.[8] Ursie[9] & I will join him there at midday tomorrow. The Malans[10] are going too so we’ll be a nice little party.

I wish old man Schreiner[11] would have come too. I went with my little all alone to Camps Bay this afternoon.

Send me in a Post card Mrs ?Randles[12] exact address at Oxford. It’s wonderful she got my last letter as she – I didn’t put any address on it except “Oxford”

Ever thineOS.

I really felt inclined to run off with you & mother on Friday night[13] When Hansie[14] & I got to the Parliament house[15] we found it so crowded there was not one seat free, so I came home.

Love to Mother. I must finish my book[16] before you come out & she & I Ursula & Will come to look for you up[17]

[Olive Schreiner to Lyndall Schreiner, no date but Sunday 24 March 1907, 6647]

[1] The letter is headed Sunday night, while the text says Saturday. Dating, using other letters in the Olive Schreiner Letters Online collections, has taken it as Sunday.

[2] Lyndall – known to family and friends as Dot – was the eldest daughter of Will and Fan Schreiner and Olive Schreiner’s favourite niece. The letter was written soon after Dot and her father had left South Africa by ship for her to go to Cambridge and Newnham College. This way of addressing her conveys the level of feeling involved.

[3] Constance aka Con Lytton became a prominent WSPU member and prison reform campaigner. In 1908 and 1909 she came to public prominence through being treated well when imprisoned for political activity under her real name of Lady Constance, but treated brutally and forcibly fed as plain Jane Warton, and as a consequence suffering a heart attack then stroke. Her father, an estranged member of the family, was the Earl of Lytton.

[4] Maria Theresa Villiers, maternal aunt of Constance Lytton. A suffragist, she joined the WSPU in 1909. She had published Letters to young and old (Dent) in 1906.

[5] ‘The little mother’, and variants on this, was a favoured way of Schreiner referring to her sister-in-law.

[6] A number of Nells appear in Olive Schreiner’s letters. This one cannot be traced and may have been a family connection of Fan Schreiner’s.

[7] Oliver Schreiner’s husband Cron Cronwright-Schreiner. He took her name on marriage. They later became estranged.

[8] The Cape Town home of Olive Schreiner’s close friend Anna Purcell and her husband Frederick, director of the Cape Town Museum.

[9] The second and youngest daughter of Will and Fan Schreiner. At this point she was still at school.

[10] The relatively liberal Cape politician François Malan and his wife.

[11] Oliver Schreiner’s younger and much loved brother Will or WP. He was a very high-ranking lawyer and politician and had previously been Prime Minister of the Cape. He worked and smoked too much and she worried that the family heart condition would lead to his early death. It did.

[12] A number of Schreiner’s connections in Oxford are mentioned in letters, but this person cannot be traced.

[13] Because this was when she said goodbye to Dot, knowing that she would leave soon after for Britain with her father.

[14] A number of people of this name appear in letters; this is likely to be one of Fan Schreiner’s nieces.

[15] Schreiner often attended and sat in the Strangers Gallery to listen to debates, over which she cast a sceptical eye.

[16] At this date, the book referred to is what became From Man to Man.

[17] That is, when Dot ‘comes out’ in the sense of returning to South Africa and the family going to greet her at the docks.

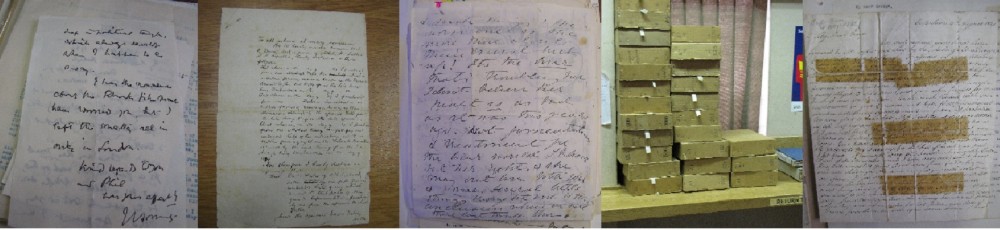

1 The letter

1.1 This transcribed letter by Olive Schreiner to a favourite niece, provided with footnotes giving information about people and circumstances relevant to comprehending it, is on one level rather inconsequential. It a snapshot of what reads like an ordinary family scene. There are expressions of affection towards the addressee and a range of family members, and the letter keeps the addressee in touch with things that have been happening, which include an uncle playing golf, a party of people she knows planning an outing, its writer going to a beauty spot, a thwarted visit to the Cape parliament, and that at a future point family members will come to look for her when she ‘comes out’.

1.2 But turn the kaleidoscope again and what is seen shapes up differently. The letter opens by saying that part of a letter from Constance Lytton was enclosed, and that Dot ‘must’ get in touch with Mrs Earle, not only both members of an aristocratic family but also becoming important figures in the suffrage movement and in particular the more radical arm of the WSPU. They are mentioned at the outset, which has the effect of injecting a note of importance to this, for what is being passed on is not just information, but introductions to some of the feminist great and good in Britain.

1.3 The sense of being among movers and shakers in a political sense is both built into the letter because of who Dot’s father was, a senior lawyer and an even more senior politician, but also contributed to by the in passing references to the Malans, with FW Malan at that point an important figure in Cape politics, and Olive Schreiner’s attempt to attend one of the parliamentary debates. Added to this, there is the reminder, if reminder was necessary, that at this point in time Olive Schreiner was one of the world’s most famous women and very active as a high-level social analyst with a string of influential essays as well as novels and other published works to her credit, and that she had a book on the go.

1.4 Not apparent with any shake of the kaleidoscope is the future. And what future knowledge could provide is, among other things, that Olive Schreiner, Anna Purcell, Fan Schreiner, Dot Schreiner, would in around two years hence become active and indeed prominent members of the Cape Town Women’s Enfranchisement League, then a year after that Olive Schreiner would resign her vice president role because national WEL officials gerrymandered to change the basis on which women’s franchise would be campaigned for, so introducing a racial criterion which she would not accept.

2 The context

2.1 The context was one which included: a Constitutional Convention meeting in the different states of the Cape, Natal, Free State and Transvaal to agree the terms on which union would take place; and what became known as the Bambatha Rebellion, which Will Schreiner became involved with as council for the Zulu leader Dinizulu in defending him against trumped up legal charges, took place.

2.2 The immediate circumstances which led to the letter being written have been indicated in the footnotes. Dot had reached young adulthood and had had great success with her law degree in Cape Town and at that point hoped to follow in her father’s footsteps as a Cambridge-trained lawyer. As the letter was written, she had just left by ship with her father for Cambridge and Newnham College. It was autumn in Cape Town and Parliament was in session. Cronwright-Schreiner was at that point a Cape MP. Olive Schreiner attended the parliamentary sessions and key debates when possible and picked up long-term friendships and family relationships; she was also there to wish bon voyage to her niece. She was an attentive correspondent; and while she wrote many letters per week, they differ considerably according to the person she was writing to.

2.3 It would seem that in spite of encouragement it took a long time before Dot Schreiner met her aunt’s friend Constance Lytton. However, she did become involved in the suffrage movement while in Britain and sold WSPU weekly newspapers as well as being involved in a variety of marches and protests. She established her own circle of feminist friends. Later, after returning to South Africa, she took over from Anna Purcell as secretary to the Cape Town WEL. In the long run, however, it was her younger sister Ursula who stayed the course in feminist terms. Dot Gregg subsequently immersed herself in domesticity and family and became a friend of Jan Smuts. Ursula Scott became a mainstay of women’s rights politics in particular in relation to contraception and birth control.

2.4 At around the time the letter was written and more clearly thereafter, the already fragile marriage of Olive Schreiner and her husband took a nose-dive, as did her health when they removed from Hanover to hot and dusty De Aar. On the surface their relationship continued, but beneath it things changed. She continued going to Cape Town and other places at periodic intervals and insofar as health permitted, picked up friendships and plunged back into political life. They lived in effect separate lives.

3 After

3.1 What changed long-term?

3.2 The women’s suffrage movement in South Africa subsequently not so much splintered as it morphed into accepting the suffrage on the same terms as men, which meant a racial franchise in three of the four provinces of the country. The Cape was the exception, as the terms of union had legislated that its nonracial franchise would remain and could not be overturned except with large majority in the Union Parliament.

3.3 Inch by inch, political rights were taken away from black and coloured groups, including whittling away the franchise until it became a nothing. Whiteness became more and more and more white. Blackness became more and more ‘other’.

3.4 Not long before her death, at the end of 1920, Olive Schreiner wrote a letter to Jan Smuts, the man above all others who was responsible for a succession of retrograde turns in South African life. It is one of her great letters and tells him that the past is over and the day of autocracies has gone, that it would go in South Africa too, and that he had one last chance to do what was right in racial terms. She knew that he would not take it. To read the letter, click here.

Last updated: 11 January 2020