Letters by Njube son of Lobengula, 21 Sept-21 Oct 1898

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2017) ‘Letters by Njube son of Lobengula’ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/LettersByNjube and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

1. Lobengula was the last king of the Matabele (the Northern Ndebele people, in what is now Zimbabwe). Cutting a long and terrible story short, many concessions hunters queued and hustled for access to Ndebele land in search of what they thought (erroneously) would be massive deposits of gold. Leader of the pack was the so-called Chartered Company, the British South Africa Company [BSAC]. The 1888 ‘Rudd concession’ gave Cecil Rhodes and partners (including Charles Rudd) exclusive mineral rights in much of the lands east of the main territory. Gold was already known to exist, so with the Rudd concession in possession Rhodes et al were able to obtain a royal charter to form the BSAC in 1889, which could operate across the wider area under license. The concession hunters and others required to explicit permission to be present in Matabeleland. The BSAC troopers, police and so-called Pioneers arrived by a non–direct route through the then-Mashonaland.

2. In August 1893, a Ndebele attack on the Shona provided the BSAC and its troopers with Maxim guns with an excuse to attack the Ndebele stronghold of Bulawayo, hoping to capture Lobengula and take over their territory entirely. Lobengula burned Bulawayo and escaped to the mountains; he later died (or rumour at the time had it was killed by his indunas) and buried secretly. The first Matabele war ended.

3. In March 1896, having tasted the BSAC’s ruthless frontier rule, the Ndebele rose in full-scale warfare, this time avoiding head-on battle in favour of guerilla warfare. A very large number of Ndebele warriors based in the Matopos hills were joined in the war by their former vassals the Shona. A year of many thousands of deaths in fighting ensued, accompanied by drought, cattle sickness and resulting famine, and was followed by the assassination of a key Ndebele spiritual leader, Mimo, sometimes associated with a particular person, at others having more diffuse presence.

4. The event of Rhodes supposedly unarmed going into the Matopos hills and singlehandedly negotiating peace – see Two Cecil Rhodes letters paragraphs 4.4 to 4.12 – occurred in October 1897. This was an ersatz event, a piece of mythology in the sense that the event took place through negotiations by Johan Colenbrander, who was trusted by the indunas while Rhodes was not; there were others with Rhodes; they certainly all had guns; it was written about in these terms at the time but was then represented as the stuff of legend concerning Rhodes; and, a double-dealer as ever, Rhodes’s promises to Colenbrander were then reneged on. But subsequently and almost by default, the second Matabele war ended, with the Matabele and Mashona indunas probably recognising the inexorable, rather than the persuasive abilities of Rhodes.

5. The sons born after Lobengula ascended power were seen as his heirs (the Matabele succession was complicated, but these were all in the frame for at least some groups). The eldest was Mpezeni [c1880 – c1897] and should have succeeded; however, he died of pleurisy in Somerset Hospital. He was followed by Njube [c1880-1910]; the youngest was Sidojwa [1888-1960]. All three were sent by the BSAC, with Rhodes’s personal involvement, to Cape Town for ‘protection’ and education, with Njube attending Zonnebloem College, a mission-founded establishment. By 1897, the leading indunas were calling for Njube to return to then-Matabeleland, for the Ndebele were not a nation without a king. The BSAC and the Cape Governor refused, thinking this would probably provide a point of coalescence for the many Matabele discontents with Chartered Company rule.

6. Some hints and glimpses of Njube Lobengula when in Cape Town are provided in Cecil Rhodes: The Man and His Work), a biography by Gordon Le Sueur (1913, London: John Murray). Le Sueur was one of Rhodes’ secretaries/factotums, young men that Rhodes was attracted by and employed in a range of go-for capacities. He is also a notable user of casual contemptuous racial language in his letters in the Rhodes Papers as well as in this book. This particularly involves the ‘n word’, something fairly uncommon at this time except in mining circles in the South African context, but with Le Sueur a frequent user.

7. Le Sueur’s biography of Rhodes briefly describes Njube dressing in Ndebele war regalia as a kind of performance for casual visitors to Groote Schuur (Rhodes’ house and Estate) in return for tips; and also, when told that if he wanted to accompany Rhodes on a trip he would have to wash and clean and carry, he immediately co-opted the services of some of the servants working at Groote Schuur to do this for him. Both are seen as laughable and indicating inferiority in Le Sueur’s eyes.

8. The impression is that, at least by Le Sueur, Njube was treated as a butt for coarse comment and laughter. However, contra Le Sueur’s stance, what comes across instead is that the then eighteen or nineteen year old Njube was not repressed by circumstances, he had a clear sense of his position as a Ndebele leader and what was due to it from other Africans, he wanted to get out of Cape Town back to the north, he had fairly close access to Rhodes, and he was short of money and tried to get some.

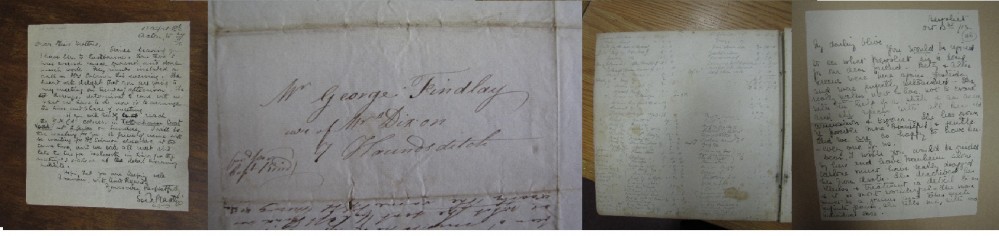

9. There are four letters from Njube Lobengula to Rhodes among the latter’s personal papers, all written in the period Le Sueur’s biography refers to (Letters by Njube son of Lobengula to Cecil Rhodes, Rhodes Papers 27/92,6; 4292-4301). What might be indicated by these remaining traces written by the young man himself? Detailed extracts from each letter are now provided. These are verbatim, warts and all, and with mistakes crossed through, insertions shown ^thus^, and omissions indicated with …; there is some commentary on each letter-extract in turn, with a brief more general discussion at the end.

10. Letter One

21 Sept 1898

My Dear Master

I have done great foolishing Excuse me please Sir. I will not do such thing as this I make mistake by writing, I did’n’t mean to do it. To speak to you like that.

My good master excuse me Please

your Faithful

Njube Lobengula

11. This short letter shows considerable facility with regard to Njube Lobengula’s use of the then-current conventions of letter-writing, with its ultra-polite form of address at the start and its elaborate sign-off at the end. Its form of address is however an exaggerated one, reinforced by repetition of ‘Master’ when addressing Rhodes, which thereby becomes a form of title. The whole of the letter is in fact an apology for having ‘done great foolishing’, although what this consisted of is not elaborated other than that it involved him speaking or writing to Rhodes ‘like that’. It is also unclear whether this occurred in speaking or writing, as both are used in consecutive sentences. However, what is apparent is that either Rhodes was offended or else Njube Lobengula himself had the sense of having gone too far in whatever was expressed and that apology was called for or was politic.

12. There are different ways that the tone of this letter might be interpreted. One is that its deference expresses Njube Lobengula’s subjection in terms of racial hierarchy. This is however to ignore that he had been earlier schooled in the niceties of Ndebele culture and what was deemed appropriate for someone of his age and standing and also his position in relation to Rhodes, in effect the ruler who had replaced the defeated Lobengula. Lobengula’s son has considerably more than functional literacy in both English language use and also writing, while at the same time polite Ndebele expressions and correct forms of signaling acceptance of social hierarchy might well have come across to the less than culturally sensitive Le Sueur, not to mention Rhodes himself, as a kind of inferiority rather than sophistication.

13. Letter Two

23 September 1898

My Dearest Master

I want money please Sir for my pocket. And for when you are away that I may have my money near to me And I only want £2 Sir… And I want £1 for Trams which I have owed some one his Tram Picture. And I want to give him back his money.

For your Kindness please to help your Servant

I Remain

your Faithful Servant

Njube Lobengula

^… Sir I was working for my pocket money I want some book Sir^

14. The comments above about the letter and its conventions and Njube’s considerable facility regarding these also apply to this second letter, as do earlier comments about his use of an ultra-polite and indeed deferential mode of address and sign-off. There are however no repetitions of the ‘Master’ address – this is a letter of request and not apology. The request is for ‘money please Sir for my pocket’, and that it goes on to invoke wanting to ‘have my money near to me’ implies an entitlement that shifts request some way towards being a demand for what is his.

15. The letter expresses this in terms of difficulties: Njube Lobengula has had to borrow money, which the person concerned needs to have re-paid. As well as in his terms most likely occasioning a disturbance in his (leadership) relationship with others, the multiple repetitions of variants on ‘money for my pocket’ in this letter convey that he was kept on a tight financial rein, for reasons which become more apparent in the third letter to be discussed. However, the PS to this letter provides an acceptable reason for why he wants money, to buy ‘some book’, although its appearance only at the tail-end of the letter rather removes any persuasiveness it might have.

16. Letter Three

14 Oct 1898

My Dearest Master

Will you please let me go Home fore Holiday…. And will you tell me how many days I can stay there and after those days… I will come ^back^.

I will always do what you want to

Please sir for your Kindness

Njube Lobengula

17. This letter-extract has been considerably shortened here, with the ellipses indicating untranscribed passages which repeat ‘let me go Home’ and that, ‘after those days’ as agreed by Rhodes, ‘I will come ^back^’. The terms in which the letter is expressed – including ‘Master’ and ‘your Kindness’ – indicate that this is a request and does not have any demand implication to it. The words ‘Home’ (rather than kingdom) and ‘Holiday’ use the conventional rather cosy idioms of white writing. But being repeated many times in this letter undoes this effect, for it comes to have a ‘the gentleman doth protest too much’ quality to it as a result. But why should Njube have written like this?

18. Letter Four

21 Oct 1898

My Dearest Master

Please sir, will you let me go Home just for Holiday only. I will not ask you any more when I have been Home. Will you please have mercy on me.

Please sir, I tell you do not think that I will rebell against you.

How can I do wicked thing against you because you are so kind to me. And you have to be so careful to me. And giving me what I want…

Please sir have mercy on me that I may go and see my Friends at Home and I will come back as soon as you want me to come back. And I want to seek for some business and if I see that I can’n’t have any things to do there I will come becau back again as soon as you want me to come

I remain

your Faithful

Servant

?by Njube Lobengula

19. After this third letter opens with ‘My Dearest Master’, the main mode of address then becomes its repeated use of ‘sir’. Also the ideas of ‘Home’, a ‘Holiday’ and ‘seeing my Friends at Home’ are once more emphasised, together with ‘I will come back’. The work these do is with respect to Njube Lobengula naming and rebutting the reason why his request is likely to be refused: ‘do not think that I will rebell against you’. This expresses in the active voice the reason, that he might actively rebel; although the rationale was perhaps more likely that even if he did not, nonetheless rebellion would cohere around his presence. And lack of money would have made it difficult if not entirely impossible for him travel.

20. This letter expresses rebellion as ‘wicked’ because Rhodes was ‘kind’ and had been ‘careful to me’, factors which perhaps set up a quid pro quo relationship of perceived reciprocities for Njube Lobengula, for the ‘father replacement’ aspect of Rhodes position might have led to a sense of being at Rhodes’s command. However, there are some countervailing aspects to the remainder of Njube’s letter that are explicitly expressed and need to be taken into account. There is both a sense of courtly politeness and conveying being at someone else’s command, and at the same time clearly stating that ‘I want to seek for some business’ and if ‘I can’n’t have any things to do there will I come back again…’. Njube Lobengula was his father’s son and appears to have retained the sense of needing and wanting to maintain links and his position among the Ndebele.

21. A few brief general points in conclusion.

22. The surface simplicities of the phrasing of Njube Lobengula’s four letters brings into relief aspects of ‘the letter’ regarding its then-current conventions. Back then in 1898, there were clear expressions of deference and hierarchy built into ‘proper’ forms of address and sign-off. That he both observed and exaggerated these can be interpreted in various ways, but one of which is that rather than unfamiliarity or inferiority, Njube was giving voice to the conventions of courtly Ndebele society with regard to a powerful chiefly figure when addressed by a younger and less powerful man. Succinctly, he was in a well-defined hierarchical relationship with Rhodes, who was acting in lieu of his deceased and defeated father-king.

23. In all four letters, Rhodes has a curious absence/presence character. In letter one, Njube Lobengula has done something and Rhodes/Master is assigned a reactive rather than agentic role, which is to excuse or otherwise whatever this was. Regarding letter two, he wants something, and Rhodes/Master is positioned in terms of providing or not providing money to him. In letter three with its multiple ‘let me’ requests, the ‘Dearest Master’ has more capacity for positive action but at the same time has no greater presence in it. Letter four continues the ‘let me’ requests made to ‘Sir’, who is given a negative role of ‘do not think’, as well as in a more roundabout way being able to propel Njube’s movements, for ‘when you want me to I will come back’. Overall, the absent and unnamed Rhodes is Master and Sir and is recognised as having authority and rule, but at the same time he is also largely positioned as lacking in force apart from in acts of withholding.

24. Among other things, these letters raise the interesting matter of how to tell when a letter-writer is going through the motions and writing what they have surmised to be what someone, in this case whitey, wanted and required, and how Njube Lobengula ‘really’ thought and felt about his situation and Rhodes in relation to it. Perhaps there are aspects of both ‘what whitey wanted’ and was he ‘really’ felt, but how to pin this down regarding the representational heterotopia of letter-writing remains a key question.

25. How to read a letter’s tone as well as surface content under such complex circumstances as Njube Lobengula was living through is not self-evident, then. There is a need to guard against presentism and imposing the understandings and beliefs of the present on the past. Perhaps in particular this means avoiding imposing a retrospective disempowerment on Njube Lobengula – ‘he’s oppressed! he’s abject!’ – by failing to recognise what has been highlighted here, which is his considerable facility and subtlety in using variant forms and complex modes of expression which signal aspects of both independence and non-compliance as well as expressing compliance and difference.

Last updated: 29 December 2017