Hear the trace, 15 December 1915

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2019) ‘Hear the trace′ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Hear/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

1. On 15 December 1915, Jim Forbes, the youngest surviving son of David and Kate Forbes, then aged 49, married Olive Mathews. Theirs was a small wedding, in Johannesburg, with neither Kate Forbes nor her three daughters involved in any of the arrangements, although the eldest surviving son, Dave, was present as best man. The bride’s mother was ill and so could not attend, and she was “given away by her brother”. A diary entry by Kate Forbes states that, after the bride and groom left, a select gathering went to the theatre.

2. The diary entry is:

Wednesday 15 December 1915

James Forbes was married to Miss Olive Mathews in Johannesburg Maggie Dave & I (his mother) were at the Ceremony so was Mr & Mrs Sam Evans that were all representing his side Mrs Bristowe was also there

Mrs Mathews the brides mother was ill with pluerisy so could not be there she was given away by her brother & her Sister Daisy was bridesmaid there were very few there owing to Mrs Mathews illness they the bride & bridegroom went to Pretoria for the honeymoon

Dave was best manJudge & Mrs Bristowe Maggie Dave & I went to the theatre in the evening to see “Peg of my heart” there was a storm of rain & hail during the performance it was fine when the time to leave came

58 52

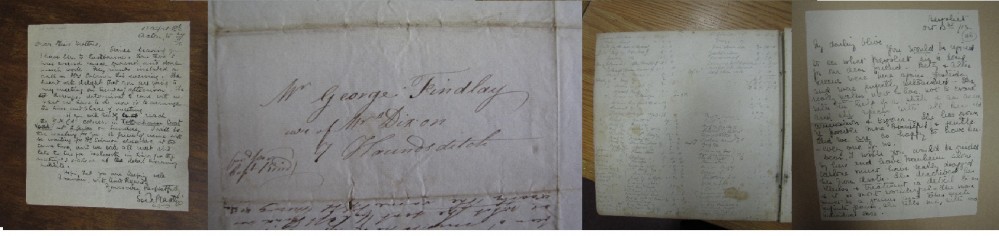

[Forbes Diaries / Box27-Diaries / 1915LettsSouthAfrican / IMG_4138.jpg]

3. The “I (his mother)” in the first sentence here is one of many indications in Forbes diary entries that it was written for use as a semi-public document. There are 24 year-volumes spanning the period 1850 to early 1918. At basis, the diary overall is a particularly detailed and extended version of a ‘farm diary’, something that was required of major farmers as part of controlling stock diseases and dealing with drought and fires, and therefore including temperatures and rainfall. In addition, as a semi-public document, the Forbes diary still contains much that was private or at least semi-private concerning their everyday lives and activities and those of their key workers. The focus, then, is generally the Athole farm-estate and associated farms, located near New Amsterdam and Ermelo in the eastern Transvaal close to the Swaziland border.

4. In this particular instance, the diary entry concerns events occurring elsewhere than Athole, although it was perhaps written up there on returning from the event that the entry writes about. In the main, the diary entries appear to have been written either on the day or within a short time of the date in question. Later diaries were set up in advance by having things like ‘temp’ written at the bottom of each page for the whole year and there are some other signs of standardisation. David Forbes senior was the main diary-writer until his 1907 death, when Kate Forbes, earlier a more occasional contributor, became the prime diary-writer. When she was away, managers and family remaining at Athole sent her daily or weekly accounts and she wrote these up as entries, even though these people may have written entries themselves. It was a responsibility the key diary-writer took seriously.

5. In the heterotopic world of the extensive Forbes diaries and their thousands of letters, who Jim Forbes is, is known and fairly well-documented, although there are still many aspects of his life and activities that remain in the shadows or invisible. And similarly so with his older brother Dave and youngest sister Madge aka Maggie, together with two sisters not mentioned – Kitty, and Nelly or Nellie – as well as his mother Kate and his father David senior. However, ‘placing’ Olive Mathews and her family is much harder still, as they were largely peripheral to the everyday concerns that Kate as the owner of Athole and so the farm diary-writer recorded, along with who Sam Evans and his wife and also Judge and Mrs Bristowe were in relation to the Forbes.

6. Jim’s wedding was a small one, with not more than half a dozen people present “representing his side”. Kitty and Nellie had stayed at Athole to oversee the running of the farm-estate while the others were away. There were even fewer present on the bride’s ‘side’. This is put down to her mother’s pleurisy having prevented her from attending Olive’s wedding. However, why this should have prevented other people from attending what was after all the wedding of Olive and not her (implicitly widowed) mother is not mentioned. Also, Athole was in the eastern Transvaal, and Johannesburg to the north and west, a long distance apart, so as the Matthews were a Johannesburg family this was perhaps why the wedding was there. However, this is not commented on and must remain just speculation.

7. Why was Pretoria chosen for their honeymoon by Jim Forbes and Olive Mathews? Nothing is known about this either. But the Bristowes lived there, and other diary entries show that after leaving Johannesburg, Kate and daughter Maggie stayed with them for some days.

8. The play that the wedding group saw on the evening of 15 December was ‘Peg o’my heart’, which ran on Broadway in New York from 1912 to 1914 and was an enormous success. A musical romantic comedy, it was written by J. Hartley Manners and starred Laurette Taylor. The play was licensed for world-wide performance by amateurs for a small payment. The film version had not been made in 1915: it was released in 1922, well after the wedding, and was also a roaring success. However, it was not an amateur company that the wedding group saw, but one of the professional companies that were licensed to perform the play and which toured in South Africa and other countries. Up to 1918, there were 229 performances in South Africa, and over 700 by 1922.

9. Around the time of the wedding, Johannesburg had four main theatres: the Standard, the Empire, the Royalty, and the Gaiety. The Globe, built in 1889, was the first permanent entertainment venue but was destroyed in a fire soon after opening. The Empire Palace of Varieties (Empire for short) was built on the same site (the corner of Fox and Ferreira streets). But which of the four theatres the play was on at has not been traced.

10. A song, written in 1913 and also titled ‘Peg o’my heart’ was inspired by the main character in this very successful musical comedy, with Laurette Taylor herself appearing on the cover of the early sheet music for it, shown above, as it is a love song sung to her character in the play and she was particular it and she was a particular hit with audiences. The first recording was made by Charles W. Harrison (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_W._Harrison) on 24 July 1913, on the Victor phonograph label.

11. The song was incorporated in many performances as well as being on ‘phonograph’, and the three Forbes and the Bristowes may well have heard it sung on the evening of 15 December 1915. If they did, it sounded like this – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mWODupYEMDI

12. What difference does sound make to comprehending the trace? There is a seduction effect. Hearing the sound Implies a kind of facticity that words on paper do not have for many people. Its immediacy and that it can be heard over and over gives the impression that ‘we’ the listener is in a strange sense actually there, for the passing of time shimmers as ‘we’ hear what ‘they’ heard and just as they heard it, conveying that this is what it was like. And where the sound involves voice, it personalises these things. Even when judgement says that these impressions are not so, that time has passed, that these things are over and done, that there is no more or less facticity in sound than there is in text, nonetheless that seduction effect is still difficult to resist. It is the immediacy aspect and the visceral quality of sound that are at work here.

13. So what of whiteness? It is sotto voce and between the lines, although this diary-entry may appear to be agnostic in race terms. The Forbes and most of their friends and acquaintances were settler colonists who had arrived in South Africa in the early 1850s and they were whites living and working on land formerly possessed if not in the European sense owned by black people. Many black people worked on these farms, sometimes for payment, sometimes as part of a sharecropping arrangement. The income generated for the Forbes was to a large extent the product of labour by black workers. The period in which this diary-entry was written was a tumultuous one, although most periods in the South African past have this characteristic. After Union there was the Land Act, there were strikes, there was military action in German West Africa, there was the Boer Rebellion, and there were also the frequently revived rumours of black uprisings (as discussed in another trace, found at https://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/traces/all-the-whites-are-to-be-killed/).

14. These were worrying times, then, and anyway there was the perpetual problem that while the whites were away or had their backs turned, their black workers frequently did less work or did it badly. This is the context in which two of the Forbes daughters remained at Athole while the others were away, for the idea that women could not be in charge seems never to have occurred to the Forbes. And it is also worth remembering that all the service work involved in the Forbes family members travelling to and from, and also them staying in, Johannesburg and Pretoria involved large amounts and different kinds of black labour. This was the inescapable fundament of life for white people in South Africa, the unacknowledged, unremarked upon, seemingly absent but omnipresent and absolutely essential labour upon which they so thoroughly depended.

Last updated: 28 November 2019