Give that Boy 1 lb of Sugar, 17 November 1883

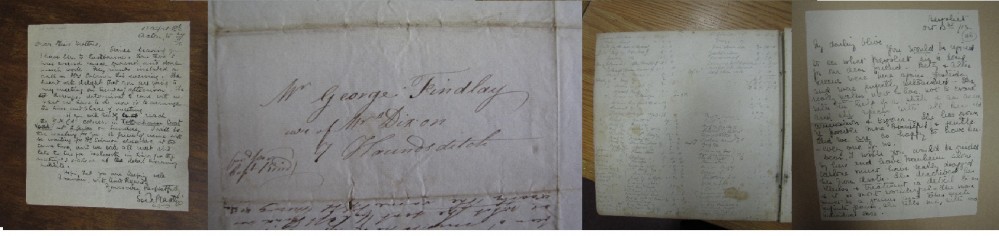

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2021) ‘Give that Boy 1 lb of Sugar, 17 Nov 1883’

www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Gallagher-7/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

Please Sir

to give that Boy 1 lb of Sugar

I will pay you Sir on Monday

you must wait for me till I have

change Because I send it ?one ?pun[d]

to this Morning at ?Magushen to

Mr Oakes to get change for him.

I am your obt. Servant

Mrs ?Umhlangwaso

?Esilongwani17 Novbr 1883

[Gallagher 7, 9308]

1. The document shown here is written on a scrap of paper. The original is too fragile to be photographed and is contained in a plastic envelope, so the supplied archive photocopy that is paper-clipped to it has been used. It is on one level entirely inconsequential, one of the hundreds of such documents that are the remaining papers of the Emagusheni trading station, located in the then-Pondoland. Someone wants some sugar, they have a pound note, but it costs much less, therefore they are arranging to get some change from Mr Oakes so they can send the money to settle the account.

2. The document is an order for goods and a promise to pay, and it is also a letter. It is addressed to a particular person and in the politest of terms, ‘Pease Sir’. This is the person running the trading station, which acted as a general store for people in the area, both white and black. It ends with an equally polite sign off and signature, and concludes with the address it was sent from and the date. The signature is itself formal in an interesting way, with Sir being matched here by Mrs.

3. It is a model letter of its kind, and at the same time it sits on the border of being a letter and being an order for goods. Ontologically speaking, then, it is already interesting.

4. Thinking about it a little more deeply it becomes even more interesting. How did it travel from the person writing the letter and signing it, and arrive with the storeman? This is implicit, taken for granted by both the addressee and the signatory.

5. Mrs ?Umhlangwaso did not run her own messages, someone would have done this for her, someone in a lower social position than she was. This was probably a boy, the same boy who is referred to in her letter when she asks that the sugar should be sent by him, and he could have been of any age up to puberty or thereabouts. In other documents some in passing references suggest that she sometimes sent an adult man who was working for her. In fact Mrs ?Umhlangwaso was a relative of the Pondo King and kept an eye on his property in the area, which included the land that the Emagusheni trading station was on, so the messenger might well have been directly working for her but indirectly working for the King. Her husband was one of the king’s most senior counsellors and a notable power in the land.

6. In terms of its content, this document is inconsequential on one level, but fascinating on another. Sugar in 1883 South Africa was a scarce commodity and highly desirable as feeding a kind of passion for the sweet. Large numbers of the orders sent to the Emagusheni store include requests for sugar and often in much bigger quantities than here. The currency that is mentioned is the British pound, with a pound note [£1] worth a considerable amount of money in 1883 local terms. This is more like say a hundred pounds in today’s values [more precisely, £109, and around two thousand South African Rand]. The contents are concerned with luxury, and affordable luxury, for the person who has written it. They indicate something about social standing and economic position, then. So does the letter as such.

7. The letter-writer is a woman, a married woman, Mrs ?Umhlangwaso, and she is fully literate. She also insists on her title by not providing a personal name. No familiarity is possible, she has to be addressed by title as well as family or other name. In gender terms this is extremely interesting, because it is an indication of equivalence with the Sir who is addressed, and it is completely performative in this. It is not possible to address her in a familiar way, it does the equivalence, it is the material accomplishment of it. In addition, it hints at something else interesting.

8. It is important in reading this letter/order to recognise that a high proportion of the documents in the trading station collections were written by local literate black people in full command of their pens, the idiom of the letter and how to write ‘proper’ examples, polite forms of address and signature, and how to get the business done of obtaining the goods they wanted and making payments for these. Specifically, there was a large mission-educated black elite that in large part mapped onto status hierarchies among the Mpondo people. This heyday of the mission-taught black bourgeoisie in some areas of southern Africa is often forgotten, but really should not be. This document from November 1883 is a small sign of something significant and important.

9. And in addition, Mrs ?Umhlangwaso, it should also not be forgotten, was a high ranking woman who was working for the paramount, the King, and married to his most senior counsellor. Polite she most certainly was, but almost certainly she would have been aware of her superior social standing and also that tenancy of the trading station and its license to operate was annually renegotiated with the King and his counsellors.

10. These factors are interestingly compared with the white people in and around the trading station, composed both by the group of storemen who shared ownership of the business, and also the flotsam and jetsam of other white people in the area. They were often barely literate, they were of uncertain social standing, many were ne’er-do-wells, and a good few lived outside of the boundaries of white society and also the law, which the trading operations often multiply breached (gun theft and gun-running was the least of it). The storeman addressed as Sir might have been white, but Mrs ?Umhlangwaso was well-connected with the power in the land, at that point not quite usurped in Pondoland.

11. This request for sugar and explanation of how and when it would be paid for shows some of the complex dynamics that characterised relationships between incoming whites, and established long-standing local black populations. In 1883, these dynamics had already shifted in white favour in some places, but in others, like in Pondoland, the old order was still in command, although things were beginning to change. Fast forward to 1894 brings this into sight, with the annexation of Pondoland by the Cape.

12. Black elites were being changed in a number of ways, through mission education, but also because the power in the land resided with traditional rulers and their entourage and these were often those most eager for change. Reading, writing, sugar, other consumer goods, point to small in themselves perhaps inconsequential practices that were adding up to something that would become incrementally momentous. The slow creaking of economic structures on the move can be heard faintly, wage labour is in process of construction.

13. There are also complexities here regarding the way in which Mrs ?Umhlangwaso is adept in signalling her social standing by using the conventions of letter-writing to do so. It is not a matter of her conceding superiority to the Sir who is addressed, for this form of address is one of the conventions and is not to be read a sign of white superiority being acknowledged. Rather the reverse. There is that insistent marker of equivalence, the Mrs, that the body of the letter ends with. Any response on paper would have required the storeman to have addressed her either as Dear Madam or Dear Mrs ?Umhlangwaso. Interestingly, equivalence is built into such conventions of polite letter-writing. And Mrs ?Umhlangwaso always signs her name thus, there is never the possibility of being familiar with her.

Useful reading

Beinart, W. (1979). ‘European Traders and the Mpondo Paramountcy, 1878–1886’. Journal of African History, 20(4), 471-486. doi:10.1017/S0021853700017497

Beinart, W. (1982). The Political Economy of Pondoland 1860–1930 (African Studies). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511558757

Bramwell, W. J. (2015). Loyalties and the Politics of Incorporation in South Africa: The Case of Pondoland, C. 1870-1913 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Warwick).

Norman Etherington, ‘Review of The Political Economy of Pondoland 1860–1930’, African Affairs, Volume 83, Issue 330, January 1984, Pages 128–129, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097586

Timothy Stapleton (2001) Faku: rulership and colonialism in the Mapondo kingdom 1780-1867 Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Last updated: 11 September 2021