‘An admixture of Native blood’, 22 February 1933

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2019) ‘An admixture of Native blood′ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Admixture/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

|

|

^K W Town

22.2.33^From C R Prance

Kelmscott

Port St John’s

Cape Province

21.2.33Dear Mr Findlay,

so many thanks. It is generous of you to add such things to what must be a full-time job. A huge boon to me, to be able to get EXACT information by return-post. I am sending to see if I can get a copy of the book.

Tell your friend Stirling, if he ever adventures this way for a holiday, not to fail to look us up without delay. Quite possibly something on my shelves of interest to him. We are apt to hear of people, just when they have been in the place a week or two & are packing up; too late to give them a run up the river, or anything.

I wonder if you know the Moggs? down here quite a long time from Xmas; he was on a “body-snatching: campaign; digging up for dead prehistoric chaps — very nice fellow, but gave me the impression of living on his nerves. She quite charmed us both. How she did HATE the place!

I know just what you mean about the type of Boer whose evidence appeared in the book. Between ourselves, I’m sure that unattractive character arises from an admixture of Native blood; tho’ I have known men obviously Coloured (though officially ‘European’) who showed no trace of it. But I suppose, too, that it came from isolation & educational back-wardness?

The ‘Koaliesie’: I don’t know what to think. If Malan is allowed in, it will be a fraud; he will be the Judas working from inside to convert it to a refurbished “Nationalism”. If he breaks away, definitely to rally the republicans as a new Party, we shall at least know where we are, which we never did yet. But I’m full of admiration for Smuts, not allowing himself to be spoofed & stampeded by Tielman Roos.

Only 1917 when Roos was declaring the need for unlimited independence, saying that Smuts’ idea of sister-nations was allbunk. I’ve been reading Neame’s Hertzog – a fruity book.

I’d far rather have seen a slashing S.A.P. victory at the Poll; though certain to be followed by labour trouble fomented by the Nats. BUT, we have the Poor White on the List now, here & in Natal; & I’m doubtful if the S.A.P. as such wld ever get in again on a straight party struggle, with the Malans & Strydoms bellowing “Black Peril” & “English Peril”. That was a fatal blunder of Smuts, letting Hertzog enfranchise the Poor White Woman — If the S.A.P. had voted solid against it, I doubt if it would have gone through, as the Klerks misliked it. However, its done now, and if the Coalition fails (or when it breaks up & Super-Nats come in again) we shall see British ‘nationals’ disfranchised, and Malan in full power. Nice prospect?

I hope you’re all well, including your Father. ^which might amuse him?^ ^W’s [unreadable]^ Very trying summer here; the worst I remember.

In haste,

Yours very sincerely,

CRP

1. Introduction – the context

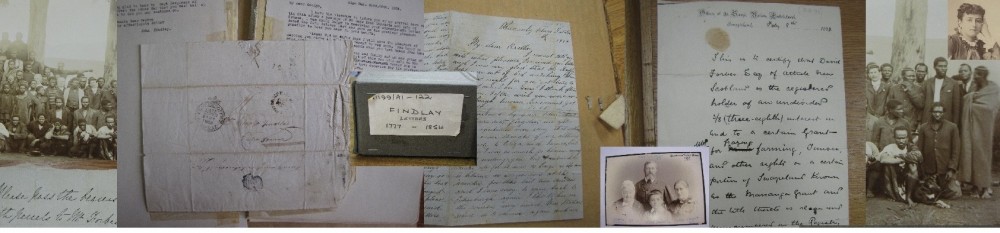

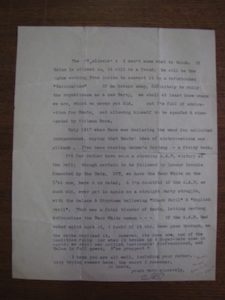

1.1 The first page of a typescript letter written by lawyer CR Prance to a friend and former law practice colleague George Findlay is shown above, with a transcript of the entire letter. It was written in early 1933, after Prance had removed from Pretoria, initially to King William’s Town and then to Port St Johns in the ‘Wild Coast’ area. There are just five Prance letters in the Findlay Family Collection, written between 1925 and later in 1933. The two men seem to have been former office acquaintances who periodically kept in touch, perhaps because of some shared political views, which are touched on in Prance’s letter. The letter when looked at closely conveys the complicated relationship between political changes occurring at state and macro level, and those occurring at local and inter-personal levels, around that date.

1.2 Prance’s letter was written in a wider context of political changes occurring at a national level and which were indicative of wider changes regarding the rise of nationalism in South Africa and the ways this was impacting on governance structures in Pretoria. Broadly, this was a process of ‘Afrikanerisation’. It was consequential for the legal profession and other higher- level organisations and professional groups there, indeed elsewhere as well, with English-speakers sometimes side-stepped, side-tracked, passed over, and on occasion ousted from paid and also voluntary positions. English-speaking members of the University of Pretoria Council, for instance, record being pushed out. It also had much wider reverberations, with National Party governments promoting ‘volkskapitalisme’.

1.3 More broadly speaking, the context also included the growing prevalence of ethnically and racially prejudiced attitudes more generally in the context of the rise of fascism, which was occurring not only in Europe but also in South Africa and at the heart of the political establishment. This too can be glimpsed in the details of Prance’s letter.

2. Before the letter

2.1 Prance’s letter is among other things concerned with maintaining social and professional bonds with a colleague who was also the son of high ranking Pretorian legal figure, JHL Findlay, who had been head of the law practice of Findlay & Niemeyer while Prance was in Pretoria. He is the ‘your Father’ mentioned in the inserted comment at the end of the letter.

2.2 Prance’s letter was written and sent as part of a set of exchanges, a correspondence, and had been immediately preceded by George Findlay sending Prance a book and it seems advancing some rather dubious views about ethnicity with regards to Boer people. But it needs to be remembered at this point that both sides of the correspondence do not survive and there are just Prance’s comments about this to go on, and Findlay’s views could have been more toned down than Prance implies.

2.3 Prance was at this point resident in Port St Johns, a long distance from Pretoria and rather cut off from his earlier contacts. As well as maintaining his friendship with George Findlay, his letter also seeks to initiate some additional ones, with the names of Stirling and Moggs and his wife mentioned.

2.4 The immediate circumstance for Prance replying to Findlay’s letter, then, is responding to the arrival of a book, topic and title not known, which had been sent to him, together with replying to something in George Findlay’s letter about a ‘type of Boer’. Also part of the immediate circumstances but somewhat more removed are his more hesitant ‘I don’t know what to think’ comments about the consequences of the inconclusive 1933 election, unsettled political situation and the formation of the Coalition. Correspondence and the continuation of letters and replies requires a dynamic which propels each exchange in turn, with here the arrival of a book and opinion occasioning the return provision of thanks, information about mutual friends, the advancement of opinion about people, and conjecture about political developments.

2.5 It also has to be remembered that letter-writing is a representational matter. It emanates from the point of view of the letter-writer in association with how they perceive their relationship with the named recipient, and this conditions what can and cannot be written, and how it should and should not be written. Letters are complicated, not the repository of ‘the facts’.

3. What the letter writes

3.1 This letter is one of many thousands in the Findlay Family Collection in Historical Papers at Wits University in South Africa. It is one of only a handful from CR Prance to George Findlay, with no further information being recoverable about Prance’s names, the details of his occupation or anything else, except that he self-published a number of books of short essays while in Port St Johns.

3.2 The letter starts by being phrased as partly a letter between friends, although partly it also has a slight ingratiating tone in how Prance thanks Findlay for having sent him a book. It then continues in a way that suggests a certain comfortableness in sharing political and related views, that Prance knows ‘just watch you mean about the type of Boer’, implying that Findlay had earlier disclosed his own views in similar terms. So while the initial part of the letter is about keeping in touch and maintaining or extending contacts, it goes on in a more familiar way, initially by expressing negative views about Boers in relation to ‘Coloured’ people, the terminology of the day among some groups of whites, and then with more detail in the form of conjecture concerned with the political situation following South Africa’s 1933 election.

3.3 Prance’s views about race are both convoluted and negative, and possibly by implication so might be Findlay’s – although a necessary question-mark needs to be placed over this given the absence of any letters by him. The ‘unattractive character’ of that ‘type’ of Boers in his view comes from having been mixed with ‘Native blood’. But then he switches in recognising that ‘I have known men obviously Coloured’ having no trace of this. And he then conjectures that this might instead ‘come from isolation & educational back-wardness’. What clearly comes across is Prance’s dislike of Boer people and a small willingness to recognise that ‘black blood’ may not provide their supposed negative attributes.

3.4 While this is written in a way that gives a show of being measured, what comes across is instead that the ‘unattractiveness’ is that of Prance. This impression is reinforced by further comments a few paragraphs on with regards to ‘Poor Whites’, women, and associating ‘Black Peril’ campaigns as on a par with nationalist tub-thumping by leading politicians Malan and Strydom with regards to English-speakers.

3.5 Prance’s comments about the political situation, the coalition, and the possibility of an extreme form of nationalism gaining political control, are quite detailed and with regard to the latter prophetic. In his view, Smuts had made a ‘fatal blunder’ by agreeing that Hertzog could enfranchise Poor Whites, and Poor White women in particular, by implication seen as particularly supporting nationalism. All the more surprising, then, that in a previous paragraph he writes that he is ‘full of admiration for Smuts’ in not supporting Roos, another political figure on the right of an already retrograde nationalism.

3.6 For Prance as for many others, it seems it was the spectre followed by the actuality of ‘Super-Nats’ that led them to see their own position as well as that of Smuts as in effect a liberal one. This is of course wrong. Faced with a lesser evil and a greater one, it is important to recognise that both are evil while still differentiating between them around degrees and kinds of offensiveness.

4. Afterwards

4.1 This letter of February 1933 is the penultimate of the small number that Prance wrote to George Findlay and there is no information about ‘what happened next’, if anything, regarding their epistolary friendship. The letter that followed is dated October 1933 and has similar content to the February one, although there is more general comment about what he is doing, comments about ethnicity and race are more subdued, and the political context and being ‘sold a pup’ by Smuts is of concern. And as noted earlier, no further information about CR Prance has been found, other than that he self-published a number of short books. Therefore whether or not he kept the letters he received from George Findlay cannot be told, nor whether there were other letters Prance sent to Findlay that now no longer exist, but certainly none exist in archival collections.

4.2 However, the Findlay collection also includes letters from George’s mother and wife sent to family members while they were away from home and written over the same period that Prance’s letters were. While not generally expressed so strongly by them, their letters certainly convey negative sentiments about ‘the Boers’ and also Jews, non-conforming women and ‘Others’ as does Prance in his five extant letters. But while such views were in a sense in the air and part of the zeitgeist for many people, Prance’s expression of them in this letter and earlier ones is quite unabashed.

5. The new context

5.1 Tielman Roos, mentioned in Prance’s letter as a troublesome political figure, failed in an attempt to refigure the nationalist political context with himself in a more prominent position by forming a new political party, and he died in early 1935. However, the Coalition and the association between Hertzog and Smuts continued for some years, while there was clear evidence, from his formation of the Purified National Party in 1935 on, of the rise of DF Malan and what Prance’s letter calls the ‘Super-Nats’. The Coalition ended when Hertzog objected to any support being given to Britain in opposing Nazi Germany and resigned after a parliamentary vote in September 1939, although there had been some significant disagreements previously. By the late 1930s related divisions within the wider nationalist framework surfaced, associated with the widespread rise of neo-Nazi allegiances in South Africa.

6. Whiteness, prejudice and representation

6.1 With regard to the political views of George Findlay, material in the Findlay collection more generally suggests that his views remained more middle-of-the-road. But of course whether this was how he expressed them in letters to Prance, or whether Prance picked up on aspects that were similar to his own ideas, is not known because Findlay’s letters to him are not extant. Therefore pursuing this line of thought has to be put on ice until detailed work on the Findlay family letters takes place, and even then the fact has to be reckoned with that letters are a representational system in which the writer is in a sense second-guessing what and how to write in ways that will be acceptable to the named recipient, and so they do not provide a one-to-one referential account of ‘the facts’.

6.2 Prance’s letters also raise interesting things about the character of whiteness in relation to prejudice thinking about ‘Others’.

6.3 Prejudice is often perhaps surprisingly intersectional in the forms it takes: across the Prance letters, racist ideas and views are mixed with ethnic prejudice are mixed with misogynistic views, and also elsewhere with anti-Semitic and homophobic ones as well. As a careful reading shows, in a rather convoluted way in this February 1933 letter from Prance, it is ethnic dislike verging on hatred that is more virulently expressed. Relatedly, in a 1933 letter written by Bessie Findlay in the same collection, it is anti-Semitism mixed with misogynistic and veiled homophobic views that are more virulently expressed. This is certainly not to say that matters of race and racism are absent, for they are not; but it does seem that on some occasions other prejudices and dislikes or hatreds took precedence.

6.4 What comes across generally from Prance’s letters is that he had rather extreme negative views about a large range of people and things and these views were, as in his February 1933 letter, interconnected and elements of which sometimes reinforced and sometimes to an extent mitigated the other elements. And overall, it is his views about women that come across as the most extreme and filled with anger and negativity.

6.5 Where does this leave thinking about whiteness? It suggests that it can be complicated, it can involve not just negativity but hatred, it can be intersectionally connected with other negativities, and sometimes the racist component can be background to other hatreds and negativities in the foreground although still present. This isn’t all that it can be, but it is all of these things at some times and in some places for some people, and for some people perhaps for all of the time and everywhere.

6.6 And where does this leave thinking about whiteness in relation to the representational world of letter-writing? Certainly there is no simple one-to-one referential relationship between letter-writing and how someone conducts themselves elsewhere in their life, for letters are crafted with the recipient in mind and are a small abstraction from the multiplicity of what could be represented in them. They are, in the terms discussed by Blanchot and Foucault, a heterotopia with its own conventions, cast of characters, plotlines, temporal order, events and meanings. This does not mean they are irrelevant or unimportant! It means that letters and the material realities they represent are complicated and this always needs to be remembered in interpreting their import.

References

Hermann Giliomee 2019. The Rise & Demise of the Afrikaners Tafelberg/Kindle edition.

Dan O’Meara 1983. Volkskapitalisme: Class, Capital and Ideology in the Development of Afrikaner Nationalism, 1934-1948 Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Last updated: 30 November 2019