White liberalism and its own reward

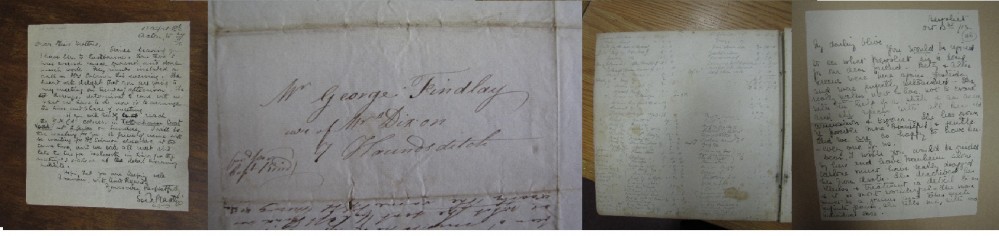

(Cory Library, Shepherd PE3682, 20 July 1960)

Charing Cross Hotel,

Strand, London, W. C. 2.

20th July, 1960

Dear Mr. Klazo,

Your letter of 17th June reached me only yesterday. I thank you very warmly for it. I handed to the Secretary of the Monkton Commission this morning the extract from your letter which speaks of how you would like your evidence to be dealt with. I have no doubt that your wishes will be adhered to.

Thank you also for the cutting you sent me from the “Mail”. For well over thirty years I was minister of what was probably the most inter-racial congregation in South Africa. Sunday by Sunday people of all races worshiped together in Lovedale, and our Kirk Session and Deacons’ Court were thoroughly inter-racial. For years my Session Clark was an African, thereby holding the chief office next to the ministers, and my Deacons’ Court Clark was a Coloured man. Yet I am described in the fashion the MAIL states. I suppose it is one of the things one has to bear, but it’s most unjust. What troubles me most is that it shows an irresponsibility in statement that does not bode well for the future, when Africans may have to carry much heavier responsibility than now.

With every good wish,

Yours sincerely,

[Robert Shepherd]

Some comments

- Robert Shepherd was the head of Lovedale College in the Eastern Cape and the other educational bodies attached to it from the 1930s until 1955. He then retired to his native Scotland but remained active in various respects, including in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland, of which he was a past Moderator.

- The letter for discussion is a typescript, a copy. But it is not a carbon copy, rather typed from scratch and with no signature at the end, which would have been provided on the version that was sent.

- Shepherd was in London as a member of the Monkton Commission, which was concerned with the future of what were then northern and southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. It recommended a majority of Africans on representative institutions and federation of these territories, which pleased neither the white supremacists nor the black radicals.

- Mr Klazo has not been traced. Shepherd was the recipient of comments which Klazo wanted to be taken account of regarding how his evidence was put to the Commission.

- The press cutting referred to cannot be traced as there are many newspapers of the day with Mail in their title.From the comments made, the Mail is perhaps likely to have been a newspaper in one of the three countries concerned.

- At various points there were debates in the UK House of Commons about Commission witnesses making ‘inflammatory’ statements after they had given evidence. Although not stated as such, this probably means they were advocating the independence of these countries in the name of their black majorities..

- What is expressed as ‘described in the fashion the Mail states’ is likely to be that Shepherd’s liberalism was located within a hierarchical and patriarchal mode and he had remained firmly in charge at Lovedale in what was thought by some of its students to be a rather dictatorial fashion. This is the implication of his comment that in the future Africans will have a greater responsibility than in 1960, but they were not behaving responsibility at the time of writing because they had described him thus.

- Riots occurred at various points when the students at Lovedale rebelled against authority, and a bone of contention was that students who were often fully adult were treated as children. The wider context was that many of them were involved in radical groups and organisations seeking to overturn the minority white government and the various bodies associated with it, including those that were educational.

- What this says about the liberal establishment version of whiteness is interesting and with benefit of hindsight rather dismaying. Clearly Shepherd thought he was in the vanguard, and lays out his credentials as presiding over the most inter-racial religious services and institution. However, life and the world had overtaken his approach and the majority population wanted clear majority control. An interesting footnote also exists among other letters in the collection, as follows.

- A former missionary and Governor of Nigeria,Francis Ibim, who had been knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1956, resigned during the Biafran War (1967-1970) the various honours he had been awarded. Not surprisingly in context, this was because of the patent failure of liberalism to act in a principled way about Biafra.

- Earlier, in July 1962, Ibim had written to Shepherd setting out his principled disagreements with Shepherd’s position in the Monkton Commission, the ethical redundancy of that position, and that Shepherd hid hypocrisy behind his credentialism. Ibim also dared him to publish this letter in the Presbyterian Church Outlook magazine that Shepherd edited.

- The correspondence on file about this makes it apparent that neither Shepherd nor the white correspondents he had communicated with about it had any idea why a black public figure (and indeed any half-way aware person) might feel strongly about the proposals being considered by the Commission and think them outmoded and hypocritical. Shepherd and his correspondents, however, viewed Ibim’s reactions as over the top, and he has hand-written on Ibim’s letter, ‘No notice taken of this’.

- A discussion of troubles and dissent at Lovedale will be found in a WWW. publication, Liz Stanley (2019) ‘Protest and the Lovedale Riot of 1946: “Largely a rebellion against authority”?’ Journal of Southern African Studies. 44, 6. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2018.1533301

Last updated: 6 January 2022