The late Mozart’s letters: the I-perspective, the letters & Elias’s analysis

This week’s blog is a day late, due to work factors beyond my control in the shape of the culmination of student presentations and portfolios of work on courses that are my responsibility. But the wheels of the mind have continued turning in the days before and the one day after this, and what follows develops the ideas in previous blogs about Elias’s treatment of Mozart’s published letters in his Mozart: The Sociology of A Genius.

This week’s blog is a day late, due to work factors beyond my control in the shape of the culmination of student presentations and portfolios of work on courses that are my responsibility. But the wheels of the mind have continued turning in the days before and the one day after this, and what follows develops the ideas in previous blogs about Elias’s treatment of Mozart’s published letters in his Mozart: The Sociology of A Genius.

Chapter 1 is called ‘He simply gave up and let go’. Elias starts his book with the statement that, while Mozart died young of some illness, this was propelled by other factors – Mozart’s feelings of defeat because of the downturn in public appreciation of his music, and because along with this his wife Constanze’s love had also decreased, to the point that for Elias “Perhaps in the end he simply gave up and let go” (58). This is a contention, a claim, but it is made as though a statement of fact. However, Elias is too good a sociologist to remain within this deterministic psychology mode, with the detail and emphasis of his book being primarily concerned with the social structures within which Mozart and other artists were situated and how people at the time lived out the complexities that arose because of the decline of older classes and the rise of new ones, because of a profound set of social structural changes that were underway (63). Elias is clear, then, that individual persons have to be situated within an understanding or model of the social structures of the time, for “Only within the framework of such a model can one discern what a person like Mozart enmeshed in the society was able to do as an individual, and what… he was not able to do” (67). But these broad structural factors at work played out, not only at structural level, but also regarding the values and ideals of people and regarding their relationships with each other, so his account of this is much less psychologistic than his opening comments might lead the reader to anticipate, and more concerned with how individual lives interface with social structural factors.

In Mozart’s case, this involved the courtly aristocratic classes and the bourgeoisie in the context of art and in particular music, such that “many individual people, including Mozart himself, experienced as a conflict running through their entire social existence” (63-4). The longer term trajectory was from musicians being craftspeople working to the direct command of the patrons to being independent artists following the dictates of their artistic gifts within a free market, and towards the breakup of the court system and the establishment of a ‘modern’ class structure. Consequently, for Elias, Mozart’s life illustrates “the fate of the bourgeois person in court service towards the end of the period when, almost everywhere in Europe, the taste of the court mobility to set the standard for artists of all social origins, in keeping with the general distribution of power…” (64-5).

But at the same time, the interpersonal circumstances were also important in a number of respects. Mozart‘s father Leopold and to a significant extent also his mother Anna Maria treated him and his sister Nannerl in a ‘hothouse flower‘ kind of way as musical prodigies and involved them touring the then many courts of western European principalities in search of high rewards and the possibility of a permanent senior kappelmeister appointment for Leopold and then later for Wolfgang. However, as Mozart grew older and became more independent, his profound dislike of the hierarchies of the court system and its requirements of subservience, humility and denial of talent which led him to be treated as of lesser worth than a competent valet, came to a head over the dictatorial ill-behaviour of the Archbiishop of Salzburg. This led Mozart to resign his court position in favour of establishing himself as an independent composer-musician in Vienna. His mother had died earlier when they were on a tour to Paris, and this coincided with him reaching adulthood and wanting greater independence. So the resignation from Salzburg, to which Mozart had eventually returned from Paris at his father‘s command, was at the same time a bid for independence from his father as well, with Leopold‘s constant direction and admonition of his son becoming increasingly irksome. Counselled both by Count Arco, in the service of the Archbishop of Salzburg, and also his father that the Viennese public was fickle and the high profile successes Mozart quickly achieved would not last, nonetheless this was where he went and for some years achieved the kind of position as an independent composer, particularly of opera, and performance musician he desired. Eventually, though, public taste changed and there was a downturn in subscriptions for Mozart‘s concerts and over a number of years he experienced considerable money worries, and it is this that Elias identifies as the propelling factor that, with other factors, led him to ‘simply give up and let go‘.

In expanding on this argument, Elias emphasises that understanding what was happened cannot be done from a ‘he-perspective’, but must be understood from the first-person viewpoint, the ‘I-perspective’ (82). Given the plenitude of letters by Mozart himself (Elias had access to around 300 of them in published English translations), and the even greater richness of the Mozart Family Letters (about the same number, again in published English translations), this sets up the expectation that Elias’s developing argument will move to a detailed investigation of how Mozart saw the interplay of the social and interpersonal and artistic that Elias identifies as analytically crucial. However, what is detailed is in fact not an ‘I-perspective’, nor even a collective Mozart circle one, but rather the teasing out of an argumentative rather than an evidential base for Elias’s opening contention concerning Mozart’s ‘defeat’. At basis, his book tells the interpretational tale as Elias sees it; and within this framework it uses reference to and extracts from a number of letters to push home its key points. A measure of this can be obtained by looking at how the Mozart circle letters are drawn on.

The first chapter, as already mentioned, contends that Mozart ‘simply gave up and let go’ and died. Chapter 2 considers the role of bourgeois musicians in court society and the conflicts that existed, and there is just one letter reference in section 4 of its six sections. Chapter 3 is concerned with Mozart becoming or striving to become a freelance artist, and there are two letter references in section 1 and one in section 2 but none in its other two sections. Chapter 4 is concerned with the transition from craft to art with regard to court musicians and there are no letter references. In Chapter 5, the artist is considered in relation to the human being that was Mozart and there are three letter references overall, one in section 2, and two in section 4. Chapter 6 considers ‘The formative years of a genius’ and has ten letter references, in its sections 1, 2 3 and 4, but none in its remaining three sections. Chapter 7, headed ‘Between two worlds’, has twenty-three letter references overall with these appearing in all sections but concentrated in sections 2, 3, 4 and 5. Chapter 8, ‘Mozart’s revolt: from Salzburg to Vienna’, also contains a significance number of letter references, fourteen in total, concentrated in particular in its first section. Chapter 9, ‘Emancipation completed: Mozart’s marriage’, is the last chapter; it is just under four pages and one section long and has eight letter references in these.

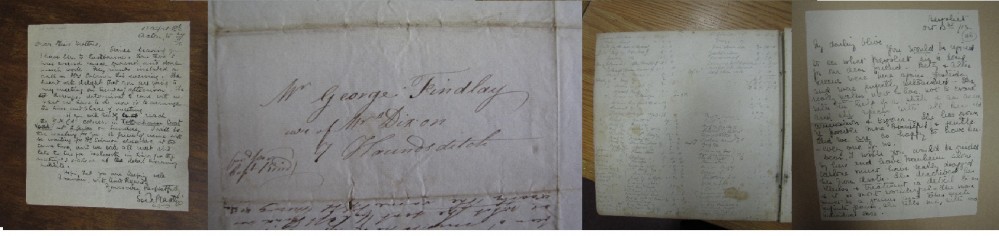

In total, 62 letters are referenced out of the more than 600 Mozart circle letters that were available to Elias in published versions. Of these, 37 are letters by Wolfgang Mozart; 18 are letters by his father Leopold Mozart; 2 are by his mother Anna Maria Mozart; 2 by a Salzburg court noble, Count Arco; 1 by a Mozart female cousin, Rosalie Joly; 1 to a third party by the Empress Maria Theresa; and 1 is a letter now known to be a forgery (which Elias notes, but still references twice). Only a minority of these letters are actually quoted from; most appear just as a reference; there are surprisingly few extended quotations overall; while, of the quotations that are provided, a substantial number are by Leopold offering his (increasingly negative) opinions of his son’s decisions and conduct.

An interesting question arises from this – at what points in his discussion and in what ways does Elias reference or provide quotations from the letters? As already noted, many of the letter references are just that, reference information provided in a footnote or in in-passing in the main text. And so how and where shorter or longer extracts are quoted from is worth considering in more detail, for this will point up the places where Elias seeks to ground his argument more securely in the letters. It may also bring the I-perspective to attention, recognising that this ‘I’ is sometimes Mozart himself, sometimes his father, and at points a small number of other people, but always contained within the authorial ‘I’ of Elias.

A very rough count of printed lines of quotations in the Collected Works edition of Elias’s book on Mozart is that there are around 70 lines of quotations from Leopold Mozart and 120 lines of quotations from Wolfgang Mozart. All the extended quotations provided by Elias, except for one, are concentrated in chapters 6, 7 and 8. Elias’s key argument has already been put in place in the five chapters previous to this, with these chapters providing exemplification of the dynamics at work. Looking at these in more detail shows the following. Chapter 6 is on ‘The formative years of a genius’ and concerns the kind of upbringing that Mozart had and how it influenced and conditioned his musical talents; and quotations from Leopold predominate, with just two much shorter extracts from Mozart’s letters. In Chapter 7, entitled ‘Between two worlds’, quotations from Leopold predominate the start, then are mixed with Mozart’s, followed by quotations solely from Mozart, with this following the trajectory of his increasing independence. In Chapter 8, on ‘Mozart’s revolt: from Salzburg to Vienna’, the quotations are all from Mozart apart from just a few words from a Count Arco letter.

So what is the next step in a methodological sense? This will be to look in closer detail at the chapters in Elias‘s book where extended quotations from letters are concentrated and to focus on how these quotations are being used and the particular argumentative purposes they serve. Progress in doing this will be the topic of next week’s blog, along with what this tells of how Elias is using the idea of the I-perspective in practice.

Last updated: 6 April 2019