And thus ‘the history’ is made

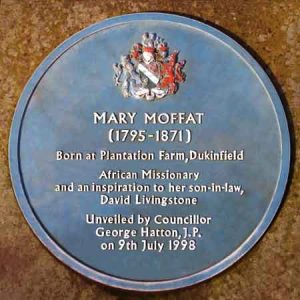

This blue plaque appears near the edge of a grassed bank on the outskirts of the small town of Dukinfield, close to Ashton-under-Lyme, Stalybridge and Hyde in the north-west of England. It looks down at the farmhouse referred to, which has seen some modification but is basically as it was when the aforementioned Mary Moffat was born there. In fact by birth she was not Moffat, this was her married surname and not that of her family of birth, the Smiths, who lived at and ran Plantation Farm, a large and successful market gardening business. The Smiths were something of local grandees because of their wealth and respectability and also because deeply involved as nonconformists in Congregational church activities. The Smiths’ daughter Mary married a man, Robert Moffat, who became a famous missionary; their son John became a well-known missionary; as a family they were deeply involved in a circle or network of supporters of missionary activity in local churches, a network that was non-denominational, extensive and spanned a number of the growing towns on both sides of the Pennine hills.

This blue plaque appears near the edge of a grassed bank on the outskirts of the small town of Dukinfield, close to Ashton-under-Lyme, Stalybridge and Hyde in the north-west of England. It looks down at the farmhouse referred to, which has seen some modification but is basically as it was when the aforementioned Mary Moffat was born there. In fact by birth she was not Moffat, this was her married surname and not that of her family of birth, the Smiths, who lived at and ran Plantation Farm, a large and successful market gardening business. The Smiths were something of local grandees because of their wealth and respectability and also because deeply involved as nonconformists in Congregational church activities. The Smiths’ daughter Mary married a man, Robert Moffat, who became a famous missionary; their son John became a well-known missionary; as a family they were deeply involved in a circle or network of supporters of missionary activity in local churches, a network that was non-denominational, extensive and spanned a number of the growing towns on both sides of the Pennine hills.

Robert Moffat came from Scotland to work in the Smiths’ market gardening business, it seems not particularly because of the gardening aspect but because of the religious connections that existed between different communities, which also extended northwards into Scotland. Their related support for the missionary endeavour was an important factor because even as a very young man he had already felt a calling. He became one of the major figures of the London Missionary Society presence and, a conservative and determined person, dominated missionary activity in southern Africa over quite a few decades. Periodic furloughs of extended leave in Britain occurred with him as a major public celebrity engaged in high-profile activity on behalf of the missionary cause. Interesting, then, that Robert Moffat rates no mention on the plaque, which apart from the curiosity of Mary’s surname and mention of the super-famous Livingstone is a very local one. It focuses on the locality and the farm and its daughter Mary, and was unveiled by someone with deep connections with the locality, as discussed later.

While Mary Smith loved and shared a strong bond with Robert Moffat, it is apparent that this love centred on religion and that above all she had shared a call to missionary work in her own right, not just as a helpmeet to him. In practice, however, the blue plaque is incorrect, because she was not a missionary in her own right. She could not live and work as this, because the LMS did not at the time recognise women as missionaries, but also because of her extensive and time-consuming domestic, family and related responsibilities, including fourteen or so pregnancies. This work of hers and of other women was crucial to the establishment, running and success of the large and multi-faceted Kuruman mission station usually associated with her husband Robert Moffat and other men. Many of her letters back to Britain lift the pen at various points and then comment on the lack of content they contain about missionary activity because this had been impossible due to these other factors. But in doing all that she did she made Robert‘s ability to live a missionary life possible, and as part of this it was she who maintained the support networks back in Britain, doing so through letter-writing whilst at base in southern Africa and through extended visits to network members when on furlough.

Rather than ‘African’ on the blue plaque, then, it should be southern Africa and specifically Kuruman. The influence of Kuruman and all it stood for impacted on a wide area and over an extended period of time. Kuruman is in an area that later in time became known as Bechuanaland, and was even later encompassed within the boundaries of what became the country of South Africa. Africa is not a country, but a very large continent with dramatically changing borders and boundaries within it because of colonial systems of governance succeeded by postcolonial changes. Generalisations about Africa, while well intended, are not helpful in conveying where the Moffats were living and working and that this was entirely beyond any frontier at the time they lived there.

And so to David Livingstone, the world‘s most famous missionary, largely because of his exploration activities. Livingstone married Mary Moffat, the eldest child of Mary and Robert Moffat. It is apparent that Mary Moffat nee Smith was less a supposed inspiration and more a thorn in the side of her son-in-law. What her letters convey is that she vocally disapproved of him as a husband and father, while grudgingly respecting his particular missionary and religious drive. This led him not to settle in one area, as the Moffats had done in the Kuruman area, but instead after a short couple of years remove himself and also wife and children to somewhere that had not experienced Christian intervention. Ever onwards, ever outwards, further and further from a missionary base, map-pen and notebook in hand.

Letters give the impression that Mary Moffat was as restrained as possible because of her respect for missionary activity, but fearful for her daughter and in particular her grandchildren. Thus on occasion she said that his family should be left at the Moffat-run missionary station at Kuruman, and if not her daughter Mary, then the Livingstones’ young children should remain there. To no avail. Earlier Mary Livingstone had been left in Britain while husband David went off on one of his journeys and she seems to have had a kind of breakdown and removed to Kendal, in the Lake District, where there was a Quaker community whose members were part of her mother’s networks and strongly supportive of missionary work. But subsequently Livingstone wanted his family with him, in particular his wife, known as Ma-Mary and seen as a kind of talisman, as a symbolic incarnation of her much respected parents and in particular her father Robert. This often took them into extreme and dangerous places in a climatic and malarial sense and there were casualties, including the early death of Mary Livingstone.

Why commemorate Mary Moffat nee Smith in 1998, when the blue plaque was unveiled? There is nothing about the date which suggests any known connection with the Moffats or Smiths. Perhaps it was related to work on the area around the farmhouse, which is close to a canal that has had considerable restoration done on it. There is however some information about the person who did the unveiling. Councillor George Hatton served over many years as a local councillor, had some years before the 1998 date been the Mayor, and subsequently played many other roles in the Dukinfield area. He is reported as being affectionately called ‘Mr Dukinfield’ as a consequence. It is possible that one of the local government committees he was involved with was responsible for the canal work, and he had known connections with the local Congregational church, but these are speculations. Perhaps his local associations were sufficient for him to have done this.

And thus is ‘the history’ made. The Smiths vanish. The rural roots of Plantation Farm and its role in supplying burgeoning local towns during the industrial revolution vanishes. Close active networks of Congregationalist evangelicals who supported ideas of a missionary calling vanish. Robert Moffat as an aspirant missionary and then a dominating LMS figure vanishes. A woman’s thwarted missionary calling vanishes. Kuruman vanishes. Mary Moffat’s relationship with her famous son-in-law David Livingstone is highlighted, and also sanitised, and as a consequence is in effect misrepresented. All with good intentions.

Last updated: 12 December 2019