The path of Ramaphosa’s letter

Readers of this blog who are attentive to news of government responses to the coronavirus pandemic worldwide will have seen that something unusual has been happening in South Africa. Swift action has included a strict lockdown affecting millions of its people living in already extremely adverse conditions where such niceties as social distancing are a fantasy. But quarantining whole communities has seemed to work, with for example an outbreak of the virus in the township of Alexandria near Johannesburg contained and infected people traced and isolated. Logistical problems are immense including with regard to feeding huge numbers of people during such circumstances, when shops and other facilities are closed to them. And South Africa has become a country used to street action and riot as a staple of political protest.

In these circumstances President Ramaphosa last week decided to deploy the South African National Defence Force to maintain order against any opposition to the lockdown. The same attentive readers might have caught a related statement earlier this week by the head of the SANDF (a kind of semi-volunteer army defence force, which has existed since the days of the Botha and Smuts government following Union of these four settler states in 1910). What he said when called before a parliamentary committee considering measures to counteract the spread of the coronavirus was that, required by the President to be deployed, the SANDF was not accountable to Parliament and would do its own thing.

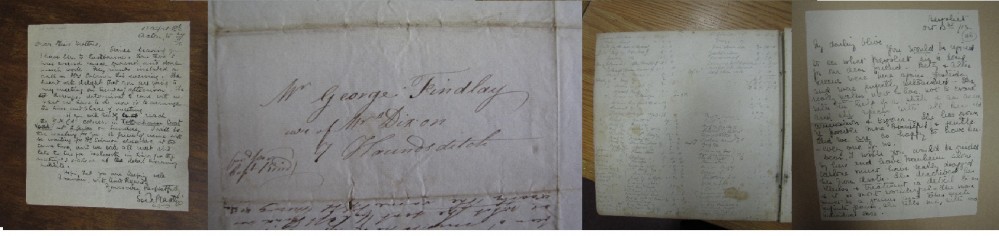

There are times when only a letter – the old-fashioned ‘words on paper’ kind with an address, someone to whom the letter is directed, a message, followed by a signature that guarantees who the letter is from – will do. Within the kind of formal constitutional democracy that South Africa has become following the post-1994 political transition, the expected path of presidential executive decision-making is that a formal letter indicating a course of action should be sent to senior parliamentary officials, who then direct this to appropriate committees for ratification.

What happened last week regarding the deployment of the SANDF did not follow this convention, as shown by some very smart investigative journalism reported on in the most recent issue of South Africa’s Daily Maverick. Yes, the letter about SANDF deployment was eventually received at this constitutional endpoint; no, it did not occur in the order that it ought; the path of Ramaphosa’s letter was constitutionally unusual to say the least. And what followed was even more unusual, and even more politically disturbing. Usually the constitutional course of things is presidentially observed, which provides the background of what is unusual here. This is Ramaphosa or his officials misdirecting the constitutionally required SANDF deployment letter to the parliamentary Joint Standing Committee on Defence and not Parliament’s leadership, which involves the speaker of the National Assembly and the chairperson of the National Council of Provinces (NCOP) then formally referring such a communication to the defence committee, with presidential letters then published in the Announcements, Tablings and Committee Reports (ATC), which is the official record of Parliament’s work.

Eventually, the deployment letter did go to the ATC, but it went after the event and in what was clearly a rushed job. Also worrying is that the standing committee on defence approved the SANDF deployment without the letter having been tabled or seen. Also deeply concerning is that Lieutenant-General Yam, the SANDF chief of staff who was appearing before the committee, made the extraordinary statement that, “the state is an instrument of government to ensure law and order is enforced” and that parliamentarians are: “not our clients. We are not the police. We take instructions from the commander-in-chief [Ramaphosa].” This is of course not so in a constitutional parliamentary system, in which the military does indeed take instruction from Parliament, as do the other political bodies concerned. A system where the military is under the direct control of a president who makes unilateral decisions is known as a dictatorship.

The path of Ramaphosa‘s letter is interesting, concerning, worrying – and how interesting it is that once more only a letter will do when important formalities are required.

Last updated: 30 April 2020