On memory, research and South Africa

This blog contains a write-up of things I spoke about in an international roundtable on this topic of ‘Memory, Crisis and Democracy in Africa’, hosted on 12 May 2021 by the Memory Studies Association. More information about the event can be accessed here [https://www.memorystudiesassociation.org/dmsa/].

This blog contains a write-up of things I spoke about in an international roundtable on this topic of ‘Memory, Crisis and Democracy in Africa’, hosted on 12 May 2021 by the Memory Studies Association. More information about the event can be accessed here [https://www.memorystudiesassociation.org/dmsa/].

The first question the organisers asked the roundtable participants to consider is,

1. What role does the field of Memory Studies play in Africa/in your research context? And would you say there is a field of African Memory Studies?

Although a sociologist, my research has been overwhelmingly concerned with historical topics in periods where living memory does not stretch, so memory, remembrance, forgetting and related terms have been central to what I do and how I think, across my academic career. And since 1994 much of my research has been about the South African past and the reverberations of claims about it in the present; therefore the same terms – memory, remembrance, forgetting, and so on – have taken on a particular inflection because of this context.

Whether there is a field of South African memory studies depends on how this is thought about and formulated, and I don’t want to make general statements about this on behalf of South African academics. What I can say is that from my perspective there is certainly a great deal of research interest in commemoration of different kinds, and it is mainly the material end of such things that has been particularly developed and produced some great work, while the trickier aspects of remembering and forgetting, which I’m particularly interested in, has been given rather less attention.

This is perhaps connected to the fact that these issues are particularly difficult in the South African context. There are always things that are not spoken about, that have been suppressed, that people self-suppress. The past and its massive silences and inequalities is of course not over and done with, but continues to reverberate in the present.

The second question given to us is:

2. What do these terms mean in an African (your specific research) context — Memory, Crisis, Democracy? How are they connected?

I’ll briefly mention three examples of work I’ve done before making a few more general comments

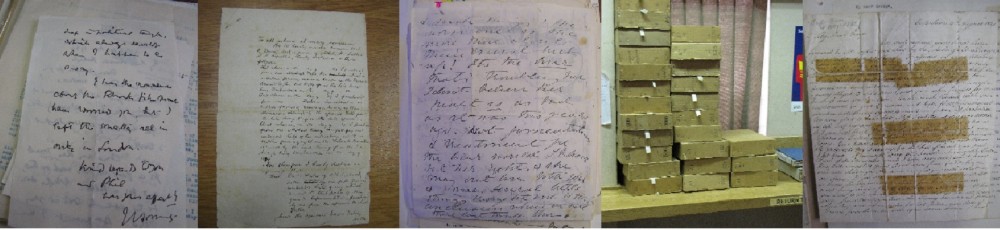

A book, Mourning becomes… Post/memory, commemoration and the concentration camps of the South African War – , resulted from a research project concerned with the memory aftermath of the South African War of 1899 to 1902, and with those who were forgotten, sometimes by happenstance but sometimes deliberately so.

This included Boer aka Afrikaner people who supported Britain, Boer men who did not fight and women who were nationalist agitators, Black people said not to be present but who were in large numbers, and children of all skin colours who suffered and many of whom died. Say war, say the suffering of children in particular, and adults on all sides are culpable.

This research recovered their names, in so far as this was possible, and followed them through part of their lives and many of their deaths, and into the commemorative record or being effaced from it. As well as archive material, it also researched camp cemeteries and their nationalist transformation into state commemoratives sites and used Bakhtin’s ideas about the chronotope, a chronotope of Afrikaner nationalist commemoration, in doing so.

This was immediately followed by the Olive Schreiner Letters Online project, which has published in full all the extant letters of Olive Schreiner, the internationally famous writer and social critic who was a key opponent both of the South African War and of the imperialist presence in southern Africa more generally,

The OSLO is now widely used internationally by many thousands of people a year. Because all the letters are there and in full, this has enabled its users to draw on the resources provided, which include many of Schreiner’s manuscripts as well, in a variety of ways. This has importantly included ‘remembering’ the South African past in a different way, by reading against the grain of earlier accounts, which have been – to put it no stronger – inflected by nationalist intentions and ideologies.

The White Writing Whiteness project followed and is ongoing. This is concerned with the period 1770s to 1970s and how whites in South Africa represented the world and people around them and changes in this over time.

Like the OSLO project, WWW publishes the research data itself, primarily letters but also other writings as well, in order to facilitate research by other people alongside the research publications that I and colleagues have produced. And this research too has been concerned with reading against the grain, focusing on the variety of different kinds of representations by differently situated groups of people and the disagreements and conflict that occurred.

So, the terms memory, crisis, democracy, are all part of the analytical frameworks of the interconnected research projects I’ve carried out, added to by nationalism, race and racism, inequality and others, including the complexities of representation, and the importance of recognising that ‘the trace ‘, the remaining traces of past lives and events, has great ontological and epistemological complexity.

Our individual researches on such matters may be more or less successful, but my particular concern has been to ensure that many more people than just me are enabled to join this collective endeavour of interrogating the past and the ways in which it has been constructed and used. This is why I always publish as much research data as possible, to encourage further research. The OSLO has been particularly successful in this, and I have hopes that WWW will join it.

The third question we were asked to address is,

3. What role does memory and remembrance play in nation-building contexts in your research context?

The role is uncomfortable, powerful, terrible, in relation to Afrikaner nationalism. Boer women’s testimonies of their wartime memories offered partial viewpoints which were both powerful and also in many ways neither the whole truth nor nothing but the truth. Commemoration of the concentration camps started out in grief and mourning but was swiftly overtaken by nationalist political forces. And the result was the takeover of the past and its replacement by a particular version of it that was central to nationalist commemoration by the Afrikaner state.

Their role is uncomfortable too in relation to more recent post-1994 nation-building, about which I will just say that race and ethnicity intersect in complex ways which also raise questions about memory, remembering and forgetting. And I will say a little more about this in a bit in commenting on recent black memorialisation.

We were also asked,

And can you give us a quick case study to show how memory politics work in your research area?

I refer to the Cape Town fire in April and its destruction of the Jagger Reading Room at the University of Cape Town and many archive collections along with it. The following day in at least one university classroom students cheered. Presumably this was because thought it didn’t matter, indeed was a good thing, because it was the destruction of the records archive records of white people, and so complicit in apartheid. I’m told they cheered even more when told that the fire had reached the Rhodes Memorial.

The flames were fierce, and memory politics are also fierce.

The fourth question posed by the organisers is,

4. Are there transnational, transcultural and multidirectional connections evoked by memory discourses/practices of remembrance and the study of memory, democracy and crisis in Africa/your context?

There are such connections, and three examples will illustrate some of the issues.

Firstly, as my comment about cheering the destruction of the archive collections in the Jagger Reading Room indicate, there is the power of the term apartheid and the sense that many non-South Africans have that they know exactly what it means and how it should be ‘remembered’.

Secondly, there is the role of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, not so much in how it handled testimony, although there are issues there too, and more in the way it has valorised Afrikaner history-making by taking its pronouncements about the South African past on trust as ‘the truth’. This was a curious and rather reprehensible strategy which was perhaps part of the nation-building program the TRC was promoting for contemporary South Africa.

The third example involves conflicting developments in South Africa concerning memory and commemoration.

A recently started project of mine, on black commemoration and memorialisation, is concerned with the ANC government’s policy of counter-memorialisation, of placing alongside and countering earlier memorials rather than removing or destroying them. This research involves tracking government agency policy documents and researching in a multi-model way its many commemorative projects on the ground. There is a research website on this which provides much of the data being collected. For those interested, it can be accessed via the WWW website.

But of course, there is something occurring in South Africa and also internationally which is in conflict with this ANC state-level of activity. This concerns the hashtag campaigns which seek to remove old memorials, rather than re-write or counter them. of which #RhodesMustFall is the best known. These campaigns have in their own terms been incredibly successful and have attracted an enormous amount of attention.

This development can perhaps be seen as a kind of litmus test concerning where memory, public memory, presently has most resonance. And it also brings with it an insistence on removal, expunging the trace in memorial terms, and so promotes a particular version of forgetting.

Last updated: 13 May 2021