A labourer, worthy of his hire

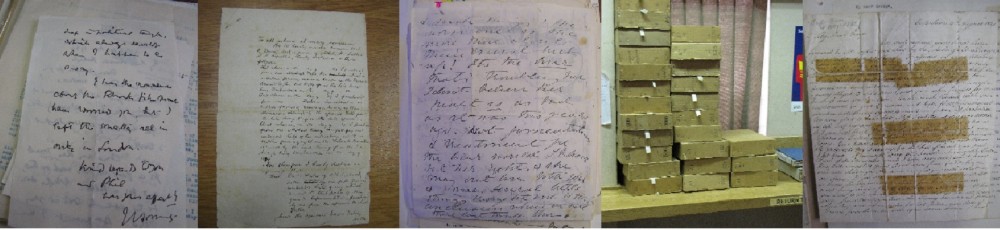

This photograph shows a document (20 Sept 1845, fm1Pringle, 179; JPG 10, 6679) which is a contract of employment between Tepa, and William Dods Pringle (known as Dods). They entered into this under the terms of Ordinance 49, a piece of Cape legislation passed in 1828 together with Ordinance 50. Unpacking its contents is helpful into teasing out some of the complexities.

Contract of service and hire under the 49th Ordinance between William Dods Pringle and Zwaartbouy – The contract takes the shape of a form completed by George Aldwych and assented to by providing their signatures by the two parties to the contract.

20 Sept 1845 – Although the form itself derives from the 1828 legislation, the contract is dated precisely as having been entered into on 20 September 1845. The importance of the precise date inheres In the legislation and is added to later in the document by specifying its duration.

George Aldwych, Field Cornet – The contract details have been entered onto the form by George Aldwych, specified as a Field Cornet. The Field or Velt Cornets were local officials who carried out a variety of legal and administrative tasks and were elected by the local citizenry [which was all male and white]. It is his presence in the document and his signature which certifies that the conditions for the contract have been met.

Zwaartbouy alias Tepa – The name of the person being hired is stated to be ‘Zwaartbouy’, but this is then added to with ‘alias Tepa’. In fact the so-called alias is the offensive Zwaartbouy, that is, black boy, with his actual name of Tepa treated dismissively.

Agreed himself – The document carefully notes that Tepa ‘agreed himself’, which makes clear that, according to the person completing the form, there was no coercion involved and that the contract was willingly entered into on both sides.

Zwaartbouy alias Tepa… a Tembookie of Kwesha’s Tribe – Tepa’s name and his community associations are then given in more detail, commenting that he was a Tambookie, and a member of a group of people at the time known as a ‘tribe’ This was/is a term that was a European invention to name social connections they did not really understand.

In the quality of a cattle herd for 12 calendar months – What Tepa was being hired to do is then specified, along with the period his labour was being for contracted for. He is being hired to herd cattle, apparently an unskilled job but one which in fact required a lot of skill and know-how, and also bravery because there were marauding animals and also marauding people who would be interested in stealing cattle and prepared to use violence in doing so. The duration of the contract is carefully specified because 12 months was the longest that labour hire contracts could be issued for, to ensure that contracted workers did not buildup entitlements to stay longer.

The mark of Zwaartbouy alias Tepa – A X or mark is included, partially obscured by George Aldwych’s writing around it. Affixing Tepa’s mark does two things in a legal sense. One is that it signifies that he was actually present, necessary under legislation of the time; and the other is that he agreed or assented, that there was no coercion, also required by legislation of the time.

Agreed and bound himself to pay the said Zwaartbouy for said service… One Heifer… and to provide… sufficient food and decent clothing during the Continuance of this Contract – The payment is specified, that is, a cow, female, and which could be expected to produce offspring and therefore increase the value of the payment; and also food and ‘decent clothing’, both of which would have a reasonable value at that time.

The O’Malley Archive, hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation website, has some detail on the ordinances that governed such contracts at that time; and in summary says:

ORDINANCE 49, 1828 Under its provisions, prospective black immigrants into the Cape could granted passes for the sole purpose of seeking work, with all employment for more than a month to be registered as contracts, Contracts for more than a month had to be in writing and in no case could exceed a year.

ORDINANCE 50, 1828 This repealed the so-called Hottentot Proclamation of 1809 and freed Cape people from the pass system and their children could not be apprenticed without parental consent. Ordinance 50 remained in force until the Masters & Servants Ordinance of 1841.

A kind of PS to act as a reminder that in practice local complexities existed along with a more controlling aspect. Below is a screenshot of an entry in the WWW database for the Pringle collection.

It concerns a legal agreement or contract between James Lewins and William Dods Pringle, dated 26 April 1849. Specifically it concerns Lewins hiring or leasing Pringle’s Cheviot Fells farm for a five year period. Among an array of other conditions to which this agreement was subject, it states that “no unhired Natives shall be located between the Homesteads of Cheviot Fells and Clifton”, both owned by Dods Pringle.

How is this statement to be interpreted, what is its meaning? It might mean that Pringle wanted the clause included to stop Lewins doing something that was outlawed under the Ordinances. It might mean that there was such a group of unhired people presently located in the area between the two homesteads or farmhouses and their immediate area and that Lewins was to remove them. It might also mean that there was a community and ‘location’ of black people living there that included both those present lawfully and those who were unlawfully so. The backcloth is that the Pringle farms abutted on to what was called the Ceded Territory, a large area of the Eastern Cape that was to be the preserve of neither black nor white, placed there by colonial administrators when the various 1820 Settler groups were given land. These farms were quite literally on the frontier and subject to many raids, but also incursions of black groups wanting access to land they had earlier had possession of.

Unfortunately, there are no further clues in papers in the Pringle collection. However, the contract of hire for Tepa and the farm lease agreement for Lewins taken together convey that even at this early point, at the end of the 1840s, there was a fairly extensive apparatus for regulating the presence and absence of black groups and communities on ‘white’ land. Some of the people being regulated might have had associations with the land in question over generations previously but who these ordinances, intended on one level to be liberal and open, in practice treated as alien and foreign.

Last updated: 24 May 2019