Tracing silence – Jan Smuts letters to May Hobbs, 1919-50

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2017) ‘Tracing silence – Jan Smuts letters to May Hobbs, 1919-50’ http://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Jan-Smuts-letters-to-May-Hobbs, and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

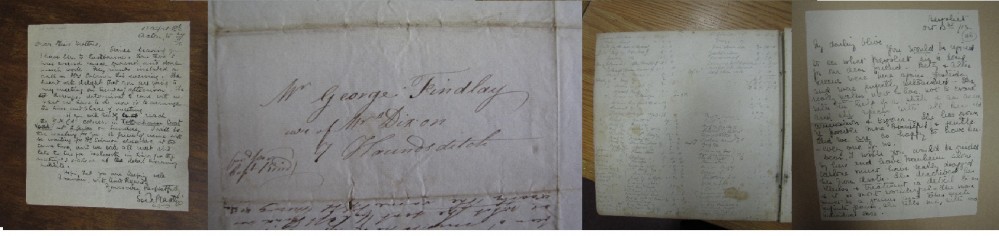

1. This is the trace – .

2. Puzzled? It’s a large ringing SILENCE, a silence rattling around in some 386 letters out of the 400 penned by Jan Smuts to May Hobbs.

3. Jan Smuts (1870-1950), a lawyer and military general turned politician, was the man who wrote the ‘race and franchise’ clause in the 1902 Treaty of Veereniging which prevented the chance of universal male suffrage; who drafted the 1909 South Africa Act and ensured both that no black franchise would exist beyond the Cape and that a provision was included enabling the future absorption of the then-Rhodesia and the African-controlled Protectorates of Lesoto, Botswana and Swaziland (which did not happen); who ferociously squashed strikes in 1913 and 1920; who did a political deal with the openly Nationalist and racist Hertzog; who gave a 1917 speech at the Mansion House promoting segregation and in effect inventing the idea of an apartheid state. Smuts inherited the Prime Ministership of South Africa following the death of Louis Botha and was its PM from 1919 to 1924, and from 1939 to 1948. Insofar as any one person can be seen as responsible for a political and state system coming into being, this is Smuts in relation to segregation, institutionalised racism and the South African state.

4. May Elliot Hobbs (1872-1956) lived in Galashiels in Scotland and was married to a farmer, Robert Hobbs known as Bert. During World War 1 she was in the Women’s Land Army and became friends with the Clarks and the Gilletts, through whom she met Jan Smuts in 1917. He was a close friend of various women in these interconnected families. At that time he was a Privy Councillor and senior army figure and was living for much of the wartime in Britain, mainly in London. She and Smuts developed what might be called a pash, passionate on her side but restrained on his and one of a long string of such relationships he maintained over many years. Their correspondence started in February 1919 and continued through to Smuts’s death in May 1950. In 1934 she visited South Africa and stayed at Irene, a farm near Pretoria that was the main home for Smuts and his wife Isie. They also met on other occasions when he visited Britain on political business.

5. Separate from other Smuts collections in the National Archives in Pretoria, there are 400 manuscript letters from him to her. They were neatly kept in their original envelopes by her and later donated by her or her heirs to the national collections. These letters are friendly, chatty and familiar, his side of exchanges between close friends who are comfortable with each other and whose relationship can sustain some frankness about disagreements or problems that arise.

6. His 400 letters can be described as more interesting for the recipient and the writer than they are for most third-party readers. They are mainly quotidien exchanges between people keeping in touch, commenting on their everyday doings, asking about the other person and what is going on in their life, and expressing mild opinions about matters of interest to them, but with little that is very exciting or controversial or out of the ordinary course of things. There are exceptions of course to this general rule, with interesting political or other matters occasionally being commented on. But these are relatively rare.

7. The very last letter is dated 11 May 1950. On a slip of paper place inside the envelope, in May Hobbs’s writing, is — “He took ill May 28 – Last letter – Only messages through Mr Cooper his faithful Secretary, who read my letters to him, when he was able to hear them & sent his answers to me – Died Sept 11th 50”. All very sad, though part of life’s rich pattern.

8. Smuts was living in a country with a large African majority. That there were then, as there are now, many black people living there would have been inescapable. The vast majority of labour of all kinds was carried out by those black people. And Smuts was not unaware of matters connected with race and race politics. As already noted, he was responsible more than anyone else for orchestrating over a long period of time the structural aspects of its race policies and its rapid movements in the direction of segregation and eventually apartheid. But.

9. But in these letters, fields plough themselves, cars drive themselves, clothes wash themselves, food cooks itself. Whatever the form of labour is, it does it itself. There is a strange, removed sentence construction used, which obviates human presence and agency, so that things appear in the form of ‘the car took me to the parliament building’ and ‘the mielies [corn] were harvested and the crop was very good’. Segregation, indeed a system of apartheid, perhaps begins in the mind and in exchanges between people with a shared mind-set which sets itself to remove from notice what it does not want to see and what it does not want to be there. The phrase ‘he did not deign to notice’ seems apt here. The people doing these laborious tasks were not deemed significant enough for their presence to be registered and recorded, while the cars, the crops, the food and the clothes were.

10. Out of all these letters stretching over those long years between 1919 and 1950, there are just a few instances of Smuts noticing the racial order around him and which he had been significantly involved in creating. They appear below, with the discussion continuing after them.

28 April 1927 “…This is a good country – lazy, easy-going, pleasant to live in, with the indispensible native to do all the hard work, and with a Nature around such as is probably nowhere else to be found.”

5 June 1929, in the wake of Labour election successes in Britain, “The more important point is what is Labour going to do? What, for instance in India, where a grave constitutional crisis is approaching? I wonder how a gentleman like Oliver is going to ride the storm. What in Africa, where Labour is pledged to a simple pro-native policy which the white settlers will resent and perhaps resist? …”

26 Feb 1930 “I have come back here into a sea of political troubles. General. Hertzog is still busy with his Native problem, but like many other looks to me for finding the solution. …”

8 March 1932, regarding May’s son Peter going to Nairobi, “Kenya must be in a bad way. Locusts have eaten up the country, and what the locusts have left (sisal) has been killed by the new British Tariff on Imports Act. And your negrophilistic public is always girding at the settlers and discouraging them. The good people in Great Britain wish to make a purely nature reserve of East and Central Africa, and may yet succeed, and Africa may revert to her primeval sleep.”

6 June 1932 “… I shall come back late at night to the farm and start early tomorrow for the lowveld. I have only a native cook boy to go with me, but I hope to pick up a couple of friends in the area I am going to visit…” in the same letter, Smuts also mentions the results of British policy in East Africa being that “I yet to see the natives clamouring for the strong hand and for the return of the Germans.”

27 July 1932 “We found a huge buffalo just killed by lions… the birds of prey had guided the natives to the kill in the morning and we found the natives grinning with pleasure as they divided the carcass and thought of the joys of overfeeding. …”

3 August 1932 “… primeval Africa… this ancient life of the earth, it enthrals me – the forest, the game, the eerie spirit, the natural savages. …”

7 Jan 1935, May’s son Peter, a colonial official, has killed two elephants, “I don’t envy Peter… I never like killing – even of game, unless it be birds for the pot. But Peter has to protect his natives and has no choice.”

27 August 1935 “I am just back from a fortnight’s tour though the Native Territories which proved most strenuous and exhausting. 4 to 5 meetings every day, besides deputations and interviews, and driving from 100 to 200 miles per day over bad roads from point to point. But the way f the politician – like that of the sinner – is a hard one.”

20 Feb 1938 Isie Smuts has “motored down… via Natal and the native territories and the South Coast to Claremont…”

5 March 1939 “We are now in the thick of our session, and my time is more than fully occupied… But our principal trouble out here is colour questions – straightening out questions between black and white and coloured in this piebald country. In addition, we have always a tangled Indian problem with us… As I wrote to Margaret [Gillet], Colour here is what Fascism is in Europe – the form the Devil assumes on this continent. Not that colour is an insoluble problem – but in these days tempers are so bad, nerves so frayed, that there is simply not the necessary patience and clam for solving and overcoming real difficulties.”

15 May 1939 “I am glad that Peter is now among the Europeans. People who live too long among natives tend to develop a native mentality!”

22 March 1947, Concerning a British Royal visit to Natal, “And I want the Royal Family to have the best feeling toward South Africa, whose policies today are frowned upon by so many other ignorant peoples. They have been able to see a country with happy people of all colours.”

22 February 1948 “The most distinguishing thing about Nakuru is the immense extinct crater near it – a fearsome object, with forests growing inside its immense inwards. The natives think it is the habitation of evil spirits…”

11. Make of these mentions what the reader will, it is the rest of the letters that is the concern here. This is because the above are more or less all the mentions of anything to do with race in any of its meanings and ramifications. This is really extraordinary, in the sense that Smuts’s 400 letters were written as though no such things and people existed, were not there, were not even in the range of possibilities, for the vast majority of the time and the vast majority of the words on the many many pages of these letters. So how should this apartheid of the mind and the pen be understood?

12. Was it, for example, a product of his friendship with May Hobbs, or that this is just the Smuts end of their correspondence? Perhaps elsewhere his letters might be very different?

13. There is something in this suggestion, for certainly his letters to political colleagues and enemies do discuss race matters regarding politics, and also different views about race and racism are raised in letters to him by Alice Clark and Margaret Gillett, in the main Smuts collection. But this is not the same as what appears (and does not appear) in his letters to May Hobbs. These are not about politics or ethics or principles, but are instead the inscription of something more everyday and quotidien and ordinary, of cars arriving, crops being picked, meals being cooked, clothes being washed, doors being opened, and so on and so on.

14. What is extraordinary is that the ordinary world of South Africa from 1919 to 1950 in which black people routinely carried out nearly all of the labour for whites has vanished, has not been seen, has not registered, has not been written by Smuts, and therefore has not been read by Hobbs. But the silence resounds, and its noisy absence can be heard by the present-day reader, who is practically deafened by it. Tracing the silence is a crucially important matter, for reducing a people and economy and polity to silence and absence is an important political tool.

Last updated: 29 December 2017