Get the boys for me, 14 February 1898

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2017) ‘Get the boys for me’ http://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/Get-the-boys-for-me/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

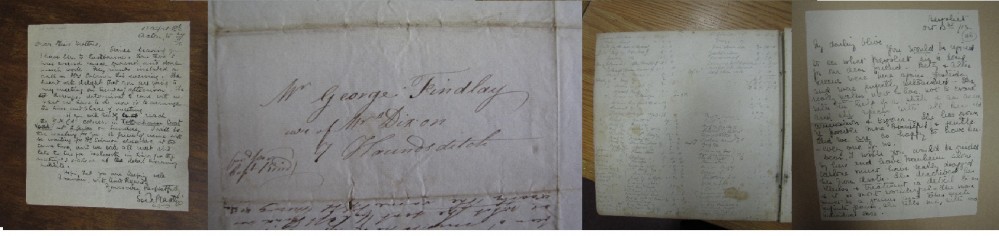

1. The trace for discussion here is a letter to David Forbes junior, almost invariably known as Dave or Mr D. Forbes Jnr to distinguish him from his father, who had the same name. It was written by Dundas Simpson, who was associated with a Johannesburg mine, with part of his role being to ensure a regular supply of labour for it. Both a photograph and a transcript of the letter appear below.

2. The letter

Dundas Simpson

Dundas Simpson

PO Box 26

Johannesburg

South African Republic

14 Feby 1898

David Forbes Esq

Athole

New Scotland

Dear Sir,

I wired you today if you could supply “300 Swazis for Clydesdale Collieries prepared to pay reasonable premium” which I now confirm.

I shall be glad if you can manage to get the boys for me as we are greatly in want of them at present. If at all possible I should like that you pay Johannesburg a visit when we could make arrangements for a regular monthly supply and I have no doubt it will prove remunerative to you. Trusting to hear from you

I remain

Yours faithfully,

Dundas Simpson

3. Simpson’s letter and the telegram it refers to were dispatched in a context in which the vast majority of African peoples were unused to, unfamiliar with, and often resistant to, wage labour in the organisations of white capital in South Africa. Agriculture and stock farming remained the economic basis, with long-term patterns of work activity and its absence built into prevailing ways of life. The idea of voluntarily working every day, every week, every month, at something outside of this was literally alien. In addition, some mines in the Rand area had very negative reputations among many Swazi men because of how they treated their workers. In groups, these men might be recruited to work elsewhere on the Rand on short-term contracts (because they had specific purposes in mind, such as purchase of a gun, or because the Swazi King had decided to send an age regiment for instrumental purposes of his own), but would refuse to work in these.

4. Dave Forbes jnr, like all his siblings, was bilingual in Setswana and English. He had also worked in prospecting and mining in Swaziland with his father, his uncle James senior and his younger brother Jim junior, and then later became manager of a Forbes coal mine in Swaziland after this was purchased by a consortium. This was his main economic activity at the point Simpson‘s letter was written, although he also had farming interests as well. Added to this, the Forbes were very much on good terms with the Swazi elite and had at various times intervened politically with Britain to protect Swazi interests from Transvaal predations. Swaziland and the Transvaal shared borders and Transvaal had its eye on both the strategic importance and also the minerals possibilities of the kingdom.

5. The particular context of the letter is that Dave Forbes jnr also acted as a manager for various other farming and mining interests (with managing leases and collecting rentals being largely conducted on his behalf by his younger sister Madge aka Maggie) and he had became known as a well-connected wheeler-dealer and fixer. For Simpson, the connections between Forbes and the Swazis were the attraction. Dave Forbes had obtained labour for the mine he himself managed (in Swaziland) and also for some others, and Simpson was trying to tempt him to become a labourer-recruiter on a much larger scale.

6. Regarding the letter itself, the first thing to note is that the person who has signed it is clearly not the person who has written the body of the letter. This indicates an office, and somebody who has acted as a secretary for Simpson. The second thing to note is that the address is on printed headed office notepaper and is a Box number, which gives nothing away about where exactly Simpson‘s office was and what organisational name it operated under. His own? Clydesdale Colliery? Or something else?

7. The letter opens and immediately gets down to business matters without any formalities or polite expressions. It refers to and quotes the key part of the content of a wire or telegram that Simpson had sent earlier that day. The information that both a wire and this letter were dispatched adds to its import and emphasis, that the letter’s content is all about communicating speedily, meaning urgency concerning the business matter referred to.

8. The business concerns securing a supply, stated in a very direct way as a supply of something required, making it sound as though this might be raw materials of some kind. ‘300 Swazis’ at first hearing or reading might refer to almost anything, and it is only after the words are inside the mind that it becomes apparent that what is being referred to is actually people, people as objects that can be ordered and supplied to the Clydesdale Colliery “as we are greatly in want of them at the present”. it also emphasises that a “reasonable premium“ would be paid, which implies something over and above the remuneration that this would attract.

9. Simpson’s request starts with “I shall be glad if you can manage to get the boys for me”, with two questions occurring in its wake. How might Dave Forbes ‘manage to get’ the boys? And why are boys mentioned? The way the sentence starts implies that there has already been communication of some kind between Simpson and Forbes, because that they could be ‘got‘ is not at issue, and nor is that Dave Forbes could do this in principle. The result is that how this might happen does not need to be inquired about by Simpson nor information requested about whether it was possible to do so, and so ‘can’ here is not being used in the sense of questioning the ability to do so. Simpson’s use of the word ‘boys’ is equally taken for granted in the letter, but its meaning and its implication needs explanation for present-day readers.

10. For many years (in some areas, centuries) after the initial European presence in Southern Africa, African rulers continued to pursue their own independent strategies and policies. However, gradually over time many strands of connection came into existence, not least because of the attraction of material objects and resources of different kinds, leading to entanglements in the white economic/political system in process of expansion. After the discovery of diamonds in the area now known as Kimberley, the then-King of Swaziland had his eye on the possibilities offered by this and required an age regiment of pre-initiation boys to be assembled, who were then dispatched to work in the mines for a short limited period to enable his purchase of guns and ammunition (with such labour tributes built into customary relationships in Swaziland). The first boys, then, were literally boys, and among the WWW letters is one from the 1870s relating that Kate Forbes at Athole had cooked on a large scale a meal for a regiment of Swazi boys going to the mines, determined they should have one decent meal while away.

11. But Simpson’s letter was written in 1898 and things had changed considerably. By 1898, ‘boy’ was widely though not yet ubiquitously used as a rather dismissive term for African men, in particular those who worked in the mines. His letter says he would be pleased if Forbes would “get me the boys”, with this having similar effect to “300 Swazis” in reducing the people concerned to an object status, as supplies that could be got by a third party for him. And the supplies here are intended by Simpson to be not just a one-off matter between them, but through a meeting in Johannesburg to be agreed as “arrangements for a regular monthly supply”, which has a further de-humanising and object-increasing effect.

12. As a ‘monthly supply’ is specified here, this may have been (but was not necessarily) the length of the contract that the Swazi men would sign up for, and if it was then this would be recognition of how difficult labour recruitment had become. Generally, however, the preference was for two or three month contracts, with the work groups concerned returning to their homes and land, but then entering a new contract after their farming and related obligations to family and community had been carried out.

13. The desired arrangement for Simson was for a monthly supply of 300 Swazi mineworkers and to ensure this he writes not only that there would be a reasonable premium but that he has “no doubt it will prove remunerative to you”. The only mentions of payment that counts for Simpson are of what would go to the labour recruiter to ensure the regular supply, and there is no mention at all of what the Swazi workers might be paid. For Simpson at least, this information was not relevant to Dave Forbes jnr being able to ensure a regular supply. The remuneration would go to Forbes, and presumably it would have then have been up to him what element of it went to the 300 men. This kind of sub-contractural arrangement whereby the work of recruitment, payment, and travel to and from a mine would be the concern of the recruiter, is also demonstrated in the papers of the few labour recruiters that appear in archive collections. See here the Trace discussion concerning ‘native agent’ and labour recruiter John Marwick at http://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/traces/supreme-court-transvaal-13-nov-1902/ on ‘In the Supreme Court of the Transvaal’.

14. Who was Dundas Simpson working for? As noted before, the printed address on his headed notepaper does not provide clues, although there are two uses of ‘we’ in his letter, one of which can be helpfully focused on in this regard. These are “We are greatly in want“ and “we could make arrangements”. The second seems to refer to Simpson and Forbes, and that if and when they met they could make such arrangements. The first refers to the ‘we‘ of the Clydesdale Colliery.

15. The Clydesdale Collieries are about 150 kms east of Johannesburg, near the present Emalaheni, and Simpson‘s reference is to the initial mine that was started there in the mid-1890s. Simpson was Scottish by background and a geologist. Among other things he discovered coal in Natal, and a seam of coal is named after him, the Dundas Seam. He was also a little later a shareholder and Director of the Premier Diamond mine, where the Cullinan Diamond was found in January 1905 (the Premier mine is near Cullinan, on the so-called diamond route east of Pretoria). This is the largest diamond ever found, of 3000+ carats, and was bought by the Transvaal government as a gift to Britain and is now in its Crown Jewels. It is said that Simpson‘s wife Ethel Fanny Boucher was the first woman to hold the Cullinan diamond, although why this is seen as significant is not entirely clear!

16. Was Simpson working as a geologist for the Clydesdale Colliery in 1898 or did he have a more directorial position? In 1889, he was the agent for the South African Exploration and Mining Company, one of the many companies formed in the wake of the discovery of diamonds and the surge of interest in the possibility of further minerals discoveries. At that time, he seems to have been in the Transvaal, then went to Natal. But so far, a blank has been drawn concerning the specifics of Simpson’s role in the Clydesdale Colliery.

17. But what happened? What was the result of Simpson’s wire and letter having been written and dispatched? One certainty is that David Forbes jnr did not become a labour recruiter, for Simpson or for anyone else. And another is that anyway events were overtaken by the lead up to, then the outbreak of, the South African War in October 1899, when the Rand mines emptied of people and were largely closed for the duration. But while this is so, it is to look narrowly and specifically at this particular letter, between these particular two white men, concerning their specific circumstances. Thinking about this in broader terms, a lot happened that was of great significance in human terms.

18. Before the South African War, but in an accelerated way after it ended in June 1902, the demand on the part of white employers was for an increased and more permanent but dispensible supply of cheap stable contract labour in mining and other heavy industries, and of more dependent and compliant cheap labour in agriculture. The Transvaal Labour Commission Report of 1904, to which David Forbes snr was a signatory and in which Dave Forbes jnr was involved as a witness, for instance, was concerned with both these lines of inquiry. While seeing them as in some sense in conflict, it also concluded that they needed to be solved together.

19. Cheap compliant labour and ever more of it was the basic demand and it led to a perception of unified white interests operating above divisions of ethnicity, language and religion, as was identified by Olive Schreiner in her letters at this time. ‘Boy’ above every other term became the signifier, in reducing men to boys and people to engines of labour supply.

Last updated: 29 December 2017