Whose collection is it?

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2017) ‘Whose collection is it?’ Whites Writing Whiteness www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/curiosities/Whose-collection-is-it/ and also provide the paragraph number as appropriate if quoting.

1. A curious question has arisen around WWW work on the Henry Francis Fynn letters – whose collection is a collection? A quick example here is that the May Hobbs collection in the South African National Archives in fact consists solely and entirely of letters written by Jan Smuts to her; there is not a shred of writing by her in the collection, nor in the main Smuts collection either. It’s not by May Hobbs at all. But at this point I can hear readers of this thinking, well, they are all to her, so what’s the problem? And how does it connect with the Fynn letters?

2. The Hobbs example is just to make the point that having something called ‘the A B collection’ raises issues about the relation between the contents and A B. Other examples are more complicated and need more explanation and puzzling over, and show the issues that arise.

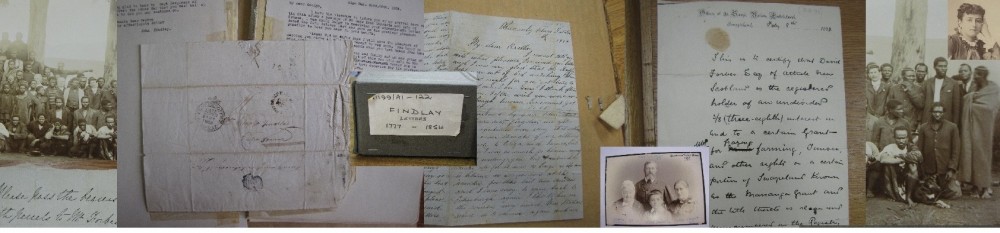

3. Enter Henry Francis Fynn. The collection here is in the Pietermaritzburg Archives depot and it is called by Fynn’s name. Indeed there are numbers of collections, both here and in Durban in the Killie Campbell Library, that appear under his name. The contents are generally referred to as the Fynn diaries, the Fynn papers, the Fynn letters and so on. Regarding the collection of Fynn letters, there are some c560 of them. But look a little closer and it becomes more complex. There are c290 letters under the heading of ‘received’, c190 letters under the heading of ‘dispatched’, c65 ‘other’ ‘letters which are mainly enclosures sent with the letters received, and a smaller group of c15 letters to and from various African kings and chiefs.

4. The letters dispatched were written and sent by Fynn himself; the letters received are those sent to him; and the rest are mainly enclosures and also sent to him. There are 142 separate correspondents involved, including Fynn himself. So just 190 out of 560 letters are in a literal sense Fynn’s letters, letters by Fynn. Also he is just one of the 142 letter-writers involved.

5. Certainly all 560 of these letters involve Fynn as the writer or the addressee or the person to whom an enclosure was sent. But they also involve the 141 other letter-writers as well, some of whom are important players to whom significant numbers of letters were sent and from whom significant numbers of letters were received. These 560 letters involve Fynn, then, as a member of a figuration that was composed of men who were, mainly, part of officialdom in colonial life and in particular in colonial governance at a very early point in the ‘invention’ of what became Pondoland (now in the Eastern Cape) and Natal, with letter dates running from 1835 to 1861.

6. This is less helpfully seen in network terms and more helpfully seen in figurational ones, because these correspondences run over a 25 year period and a high proportion of the players come but then later go and also others join in. But whatever name it is called by, the collection is composed by interrelated and entangled lives, careers, and letter-writings. It isn’t a matter of Fynn on his own, but Fynn as part of a figuration of people who were linked by some however loosely formulated and changing sense of common purpose.

7. There is of course no straightforwardly referential relationship between what is written in this 560 instances of letter-writing and the events (including the letter-writing) through which colonies were made. These letters have many of the features of a heterotopia in the sense discussed by Michel Foucault, and even more so those of the ‘space of literature’ as discussed by Maurice Blanchot. But although it may not be straightforward, there is nonetheless that at basis referentiality of the letters in referencing and representing in their own terms the events of colonisation. And these terms and views and decisions about the events were discussed, disputed, negotiated and often agreed – albeit with changes occurring over time – between the letter-writers and appear both explicitly and implicitly in these letters.

8. The bottom-line here is that calling this collection ‘the Fynn letters’ is a convenience, a shorthand. But it is a shorthand that can be rather misleading, in the sense of leading researchers away from considering the heterotropic and figurational aspects of these 560 letters, and towards putting perhaps too much emphasis on the person of Fynn himself. And as for the Fynn Collection, so too for many others as well – and not just in the WWW research.

9. What’s in a collection name? It’s curious, but probably too much – or rather too little – for comfort! Think figuration!

Last updated: 23 December 2017