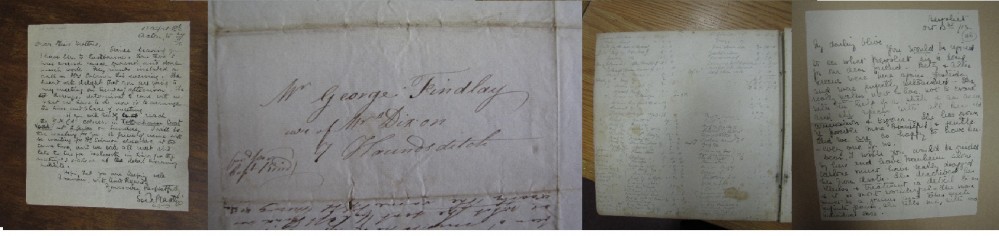

Forbes Collection, National Archives Depository, Pretoria

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2018) ‘Collections: Forbes Letters’ www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Collections/Collections-Portal/Forbes-Collection and provide the paragraph number as appropriate when quoting.

1. Overview

1.1 The Forbes Collection contains some 15,000 documents written following the emigration by some family members from Scotland to Natal and then Transvaal. They start in 1850 and largely end in 1930, with a tail to 1938. Over 5,000 of these are letters, with other contents including notes and memos, lists, tallies and inventories, accounts, diaries, maps, Wills, and a large number of business and official communications and papers. Significant numbers of the letters are from family members remaining in Scotland, although the collection contains very many more that originated and circulated specifically within South Africa. There are also many drafts and copies of letters and other documents written by the South African ‘end’ too.

1.2 Most Forbes letter-writing ceases in 1930, but with the last letters dated 1938. The collection was subsequently sold or donated to the National Archives Depository, Pretoria. There is an outline Inventory for the collection, although this is difficult to find and access, as are NAD finding aids in general.

2. The Forbes and their papers

2.1 A proportion of the Forbes Collection letters are from family members remaining in Scotland, and many drafts of ‘letters dispatched’ to them from South Africa also exist. Many more letters were written to and by the Forbes across great distances, but to family and friends who were in South Africa, and also there are many letters from and draft letters to state officials, tradesmen, bankers and business connections located in the same broad area as they were. Different kinds and degrees of absence and separation are therefore involved, but all of them occurred in the context of possibly meeting again and therefore around the tacit assumption of interrupted presence, rather than absence as a permanency.

2.2 A central sub-set of the letter-writers includes David Forbes snr, his sisters Lizzie Forbes and Jemima Condie and brothers Alexander and James; his wife Kate, their children Alick jnr, Dave jnr, Jim jnr, Nellie, Kitty and Maggie; Kate’s parents David and Anne Purcocks, her sister Sarah and brothers George, Vincent and David; and Kate and Sarah’s maternal aunt Mary McCorkindale nee Dingley and her husband Alexander. The women here wrote as much as, and when the full range of Forbes documents of life are considered, more than, the men.

2.3 Key members of this figuration of people were David Forbes and his wife Kate nee Purcocks. Their children who survived to adulthood were, in birth order, Helena (Nellie), Alexander junior (Alick), David junior (Dave), James junior (Jim), Catherine (Kitty) and Madge (aka Maggie). Alick jnr died of typhoid in 1885. The Forbes daughters had equal shares in the economic and financial aspects of family life with their brothers, although for them this resided mainly in land and crops rather than stock until after their father’s death in 1905, when they became important farmers in their own rights.

2.4 Over time, Kate Forbes became the record-keeper and accountant of the farming side of the Forbes’ undertakings and in this capacity produced lists, inventories, accounts of financial incomings and outgoings documenting the economic fabric of their Athole Estate farm, as well as drafting important letters for others and making hand-written copies of key incoming communications. Although there are fewer letters by her in the collection than, for example, her son Dave jnr, overall the majority of Forbes documents are in her hand. Kate Forbes and Dave jnr were the family archivists, for they were major letter-writers in the full sense, writing for pleasure as well as to keep in touch, also to convey information and expedite shared business and other matters in hand. They also wrote other kinds of documents of life too, including in Kate’s case, the long-term Forbes farming diary; and in Dave’s, a published memoir. They also kept and ensured the preservation of the family papers as a collection.

2.5 For the Forbes, family, household, farm, wider economic life, kin relations and entrepreneurial business activities overlaid each other and drew in not only family and kin, but also a range of friends and associates in Natal and the Cape as well as the Transvaal, and also internationally, from Scotland, England and at times South Australia, where other kin had migrated. One result is that the range of economic activities the Forbes engaged in cannot be easily (if at all) distinguished from their personal and familial relationships, with these deeply rooted in life in South Africa although also encompassing and at points relying upon equally deeply rooted connections with people elsewhere.

2.6 These economic activities were important. David Forbes with brothers Alexander and James had migrated to Natal in search of greater economic opportunities. Their sisters Lizzie and Jemima, in secure employment as a housekeeper and ‘superior’ servant, remained in Scotland. The Forbes brothers worked initially as labourers and traders. Around his marriage David Forbes turned to farming at Doorn Kloof, Natal, doing so for a commercial market. Then, through an emigration company run by his wife’s uncle Alexander McCorkindale, he purchased farms in the Ermelo/Amsterdam (then New Scotland) district from the Transvaal government. He and his family moved to one, Athole, in 1869, leasing the others. His brothers lived partly at Athole, and partly pursued independent economic interests. David Forbes was among the early ‘diggers’ following the discovery of diamonds at New Rush (later Kimberley), in doing so building up useful capital.

2.7 Close connections with David Forbes’s sisters in Scotland continued around many practical exchanges occurring in both directions. Also numerous material associations with other households connected by kinship and friendship occurred, including that at Westoe, farmed by his in-laws the Purcocks, produced many exchanges of goods, services, monetary help, and also the borrowing and lending of the labour of black workers. Forbes with his brother James also prospected and bought minerals concessions in Swaziland, some leading to mining companies floated on the stock-market, including the Forbes Henderson Mining Co. His sons David (aka Dave) and James (aka Jim) extended the economic fabric in coal mining, droving and horse breeding. Following David Forbes’s death in 1905, the Estate was reconfigured and his daughters Nellie, Kittie and Maggie and wife Kate became important farmers.

2.8 At points, the web of people linked to these manifold economic activities numbered many hundreds even excluding shareholders, with over 500 living at Athole alone.

3. The Collection

3.1 The Forbes Collection is extremely large and consists of 40 major archive boxes plus ancillary materials. It is not organised in a straightforward way, and the different parts of the collection also throw mutual light on each other, so a selective approach is liable to yield misleading results. Both the Forbes family and their neighbours and friends were major recyclers of personal names, and relatedly there were Forbes, Purcocks, Dingley, Buchannan et cetera family branches elsewhere in South Africa that also had the habit of recycling names.

3.2 The Collection Inventory is an essential aid. The Inventory, prepared in 1957, is useful and has a lot of outline detail. It exists as a paper document located amongst other findings and inventories. The greatest problem lies in locating it, as the NAD’s infrastructure of support for researchers, including finding aids of different kinds, has become somewhat shambolic. The usual recourse is to online sources, but in the case of the NAD these have mainly not been added to or corrected for more than a decade. Inevitably, in some respects the Inventory is now outdated or misleading. At points, different members of the Forbes family with the same names are confused when important features of the collection are described.

3.3 Some items are stated to be unavailable because of legal restrictions, but with these no longer applying. Some parts of the collection are now missing presumed stolen, something that applies particularly to its diaries, and within boxes there are some documents that were present in an earlier phase of WWW research but which are now no longer there; and again, these have to be presumed stolen. However, overall the Inventory remains a key resource.

3.4 The main components of the Collection are as follows:

A. Boxes 1-17

Letters received: Official; Business dated, undated, fragments; To family & friends dated, undated, fragments; From family & friends dated, undated, fragments.

Letters Despatched: Drafts; Copies.

Miscellaneous letters: Copies.

B. Boxes 18-29

Diaries

C. Boxes 30-35

Financial documents

D. Boxes 36-40

Miscellaneous

3.5 Each of these headings is described in list terms in the Inventory. However, in practice most boxes contain diverse materials, and these may or may not be dated and may or may not correspond precisely to how they feature in the Inventory.

3.6 In addition to its sheer size in terms of numbers of archive boxes, the contents are voluminous in a different way, not because there are many undated or fragmentary items (although there are), but particularly because the different elements are so interwoven that reference across its main divisions is needed to make sense of things. Neglect of particular sets of materials is liable to produce misunderstanding. Thus its small notebooks are connected with scraps of paper on which tallies of sheep or wages payments are written are connected with maps or ‘diagrams’ of particular farms are connected with diary-entries are connected with the contents of discussions in letters, for instance.

4. Diaries and journals in the WWW project

4.1 The Whites Writing Whiteness project is specifically concerned with letter-writing and the representational order that letters, from one person to another and with the expectation of response, inscribe. In addition, however, a small number of diaries and journals have been included in the sources it has interrogated, for particular reasons.

4.2 Journal- and diary-writing generally brings people up close to the fabric of their everyday activities and meetings with other people of a range of kinds, and are therefore possible sources of the writers’ recognition of the diverse character of South African populations, particular rural ones. As a consequence, some journals and diaries of people involved in a very hands-on way with farm workers have been included as a source: the David Chalmers Aiken diary of 1867-9, written in south Natal, in the absence of Aiken family letters; the 1867 John Robert Lys diary, written in Pretoria, in the absence of Lys family letters; the Mark Elliott Pringle diaries of 1911 to 1960 written in the Baviaans River area of the Eastern Cape, included to complement the Pringle-Townsend papers; the Joseph Stirk journal of 1848-1854, written in the Peddie area of the Eastern Cape, in the absence of Stirk family letters.

4.3 The Forbes diaries, written mainly in the south-eastern Transvaal, stretch over many years and act as a daily supplement to the large number of letters written by and to many members of the Forbes family. At basis, these are farming diaries and focus on the minutiae of work on the home farm and other areas of Athole and its related properties; they are not concerned with emotions and feelings and similar topics, but rather who did what work, who else was present, and what the weather and wind were doing. The two together provide a breadth and depth of family and other history over an extensive time-period that is unparalleled among South African archival sources.

5. The Forbes scriptural economy

5.1 It is not possible to generalise about the specific content of Forbes collection documents, because these involve too many people as writers and addressees, were written over too lengthy a period of time, and are from too many diverse locations, to permit this. However, there was more broadly a shared style of letter-writing that started in an emergent way, became prevalent, involved members of a number of generations, and included people living in different parts of the world, not just those in South Africa. Some general features of this can be discerned, adding up to a distinctive scriptural economy.

5.2 There is a shared approach or style to Forbes family letter-writing, which was practical performative and concerned with the matters in hand. Its focus was on ‘doing the business’, with this involving a number of things.

5.3 One, it was concerned with the continuation of relationship over separations of distance and time and did so in a practical way, through communicating the minutiae of activities and persons so as to keep the addressee in touch with the ‘actual course of things’, the quotidian fabric of everyday life matters that the writer experienced and was representing.

5.4 Two, the reciprocal communication of quotidian matters was then over time extended to encompass shared activities between the writer and their addressees, in the family context such as boxes of farming goods being dispatched from Britain and shares being allocated from the South African end, and in the Athole context such as cartloads of mealies (corn) sent to a neighbour with a request to borrow tools or plough oxen.

5.5 Three, these practical epistolary exchanges interface with other kinds of documents in the collection, as already noted, for they set in motion, expedite, query and otherwise facilitate a wide range of economic activities being engaged in, with this term interpreted broadly to cover many different kinds of exchanges.

5.6 Four, while the collection includes personal as well as business and official documents, the former are not characterised by a concern with affect or personal life and relationships, but with the fabric of everyday exchanges, with little direct concern with matters of interiority and with affect signalled via prevailing seemingly distanced codes and conventions.

5.7 The Forbes collection is composed by letters, diaries, wills, ledgers, lists, tallies… Because of the characteristics adding up to a shared approach as just sketched out, they can be seen as components in what Michel de Certeau (1984; 131-64) calls a ‘scriptural economy’; and, as a representational order, they are all part of (rather than a commentary on) the everyday. However, they also situate audience, the moment of writing, and what can be written and how, somewhat differently from each other. They are about ‘the same thing’, the everyday, but represent this in different terms, with each scriptural form – letters, diaries, wills etc – having its own conventions.

5.8 What is most notable about the Forbes scriptural economy is not that it contains what is written, but its sheer excess. The Forbes parents and offspring, sisters, brothers, uncles, aunts, cousins, friends, neighbours, business connections, shop owners, merchants, tax inspectors, magistrates and many more wrote, and wrote again. The letters circulating within South Africa provide greetings and information, while the core purpose is of a performative ‘I send you pig lard, please send me a cartload of mealies [corn]’ kind; they are very much on-going communications in circumstances of interrupted presence where people will meet again fairly soon and/or where the activities expedited by their letters are ongoing.

5.9 Thus, although not akin to talk, they are the continuation of an active relationship by means proxy to talk. Letters circulating between South Africa and Scotland show surprisingly few differences. There is more relaying of ‘news’ about things known in common to keep the other person up to date, but these exchanges too are marked by their performative character and concern shared activities of a ‘will you go to a share-holders meeting for us’ and ‘I sent you a newspaper with information of interest’ kind. There is also little sense of permanent absence or the mediation of identities of gain and loss, much more the characteristic shared with the intra-South African letters, of getting on with the shared business in hand.

5.10 These largely unschooled practical farming and business people produced everyday writings on a huge scale, with the resultant scriptural economy interconnecting with wider Forbes economic activities. In these everyday writings, the business involved is usually literally business, concerned with expediting their shared economic interests; and as already noted, they are characterised by exteriority (things, people, activities) rather than interiority, and by performativity rather than reflection or retrospection. And while it is not surprising that ledgers, lists and tallies would have such characteristics, they also mark the many Forbes diaries, which rarely mention anything ‘personal’ or self-fashioning. These typically describe the working day, its tasks and divisions of labour between different groups of workers and family members; weather patterns; and measures of high/low temperature, wind and rainfall; and only occasionally are ‘outside world’ matters covered.

Last updated: 1 January 2018