Where there’s a Will, there’s a way?

A person called Lear makes a Will, leaving everything to his three daughters, having accepted the advice of the youngest that he should not give them everything in advance of his death. Eventually he dies, the Will is proven, the property is bestowed, and in the fullness of time Lear’s Will in an electronic form becomes accessible on a British Government website.

This provides a new research opportunity for people interested in Wills and also for people interested in their relationship to other kinds of writing as well as their influence from and impact on the lived life.

The website provides Wills back to 1858. An accidental fire that year burned the British Parliament building and all its earlier documentation, meaning that those made earlier do not exist in this source. The website is free, works well and an enormous amount of information can be recovered from it.

ls a Will a letter? On one level, the answer is no, for a Will lacks individual address and in general there is no possibility of response of a kind that the signatory would receive, for if such a thing occurred this would be after their death. But at the same time, a Will has communicative intent, indeed of a kind that is given legal force, it is highly performative, and appears over a binding signature. Also significantly, although it does not have a personal address to a named individual, a Will still has a more general one that is the future, and people inhabiting it who are its legatees and will receive the items bestowed, and others who have the capacity to make its communicative intent regarding these a binding one. A Will, then, is not a letter as such, but it has some strong letterness aspects, in that it shares some of the features of epistolarity.

Wills also have other characteristics, including that their legal standing and status brings them under the rubric of the legal profession. This is not noted for the cheapness of the services it provides nor for the accessibility of the language in which its members do so. One result is that many people die intestate, that is, they have not made Wills to specify their intentions with regard to the bestowal of their estate – aka property – after their death.

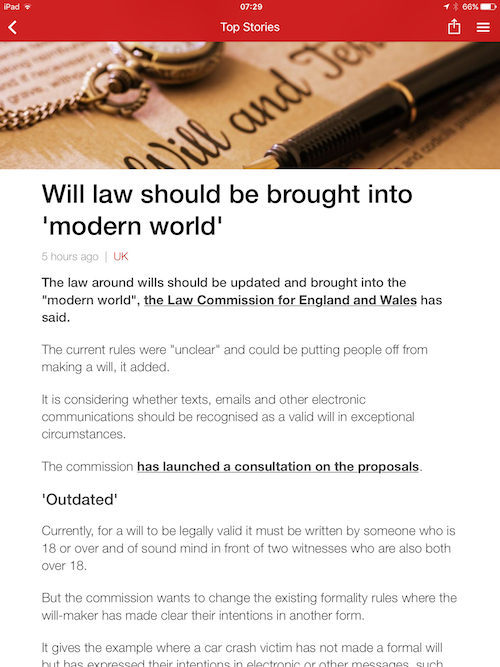

The Law Commission is now undertaking a consultation exercise as to whether other ways of signifying serious intent about such matters can and should be admitted as having similar binding aspects to Wills – as interpreted by lawyers, of course. But nonetheless, other ways of expressing this, including email, Facebook, text messages and other ways in which more people are more likely to express what it is that they want to happen after their death, are being consulted about. If this were to come to pass, it would bring Wills even more decidedly into the framework of the letter and epistolarity.

The consultation exercise runs into November and the full consultation document and also a summary version can be found on the Law Commission website.

Last updated: 20 July 2017