The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela

The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela edited by Sahm Venter, a senior researcher at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, has literally just been published this week, with details given at the end of this blog. As might be expected given the importance of the publishing occasion, this is a huge hardback book of 620 pages made available at a relatively low price (just over Br£18 via Amazon), priced so presumably because of anticipated high volume sales. The edited collection is very smartly turned out, with a beautifully designed dust jacket, a set of photographs, useful appendices, and an excellent index. The editor has done a great job of work and the result is an important contribution.

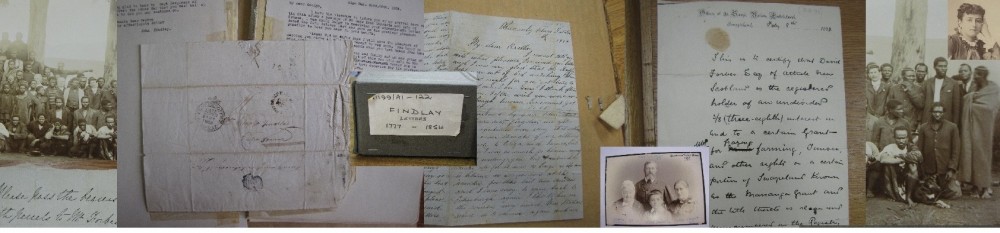

For reasons discussed in the book (xiii-xv), and also noted in The Prisoner in the Garden, discussed in a previous week’s blog on Opening an archive, Nelson Mandela‘s papers are now in many archive collections. A result is that this edited collection has taken ten years to put together. Listings of the letters it contains are provided on pages xiii and 601-3. Most of the actual letters are in the National Archives of South Africa, the others in various other locations. A large number of the transcribed letters were in fact originally transcribed by Mr Mandela himself. He copied his letters up to 1971 into hardcover notebooks before they were given to the prison authorities, later other letters were transcribed onto notepaper, because he knew that many or even most would not be sent on but filed into oblivion. This was because of petty censorship, but more particularly because of routine activities designed to wear down the Robben Island political prisoners emotionally and mentally by isolating them well beyond what imprisonment ordinarily did. These notebooks were later confiscated, and then in 2004 were handed over by the police officer who had them and are now in the possession of the Nelson Mandela Foundation.

The letters in this edited collection are presented chronologically. There is no count given but there are probably around 250-300 of them. It is not clear whether these are the total number of the extant letters written over the period of Mr Mandela’s imprisonment, although as the word selection is used in introducing the edition it is possible, even likely, that there are more in existence than have been included. If so, it is a pity that the basis for selection has not been discussed, as clearly it will have been important in shaping the account given overall by the letters provided.

Some detail – but not enough for those of us particularly interested in letters and archive collections – is given about the editing process, with its main aspects described as:

“The letters in the selection have been reproduced in their entirety apart from in several cases where we have omitted information in the interests of privacy. To avoid repetition, we have also omitted Mandela‘s address from nearly all of the letters… We have reproduced the text exactly as Mandela wrote it apart from correcting the odd misspelt word or name… very occasionally adding or removing punctuation for ease of reading… Mandela often wrote letters in Afrikaans and in isiXhosa, the language he grew up speaking, and we have noted which of these letters have been translated into English for inclusion in this publication. Some letters were also typed by prison officials and we have also noted these instances…” (xiv)

The opening of each of the main sections of the book, and some linking passages within these sections, are provided with a narrative of relevant information about events and persons. This is necessary for the general readership anticipated for the edition, and also very helpful for anyone without a detailed background in South African politics of the day. In addition, biographical information on all the people mentioned is given in footnotes attached to each of the letters; and at the end of the book there is a helpful glossary which gives some information about organisations and also provides more detailed information about the people who are the addressees of the letters. There is also a prison events timeline, and a map of South Africa and brief descriptions of places of relevance; these too are at the end of the book. A great deal of work has gone into this.

As this collection of letters has literally just been published, there has not been time to read all of its contents, let alone digests these and form any opinion. Therefore just a few broad comments at this stage, while a more detailed discussion will follow in due course.

These are the letters, not of a public or even a private man, but of a man who was allowed just an organisational face. That is, the total surveillance that Mr Mandela was under meant that his letters were always and entirely written under the gaze of outside eyes beyond those of the writer and his addressees, with similar but at a remove controls exerted over letters that people sent to him. This is perhaps in one limited respect not so different from letters of earlier times, which were seen as having collective purposes beyond the particular writer and addressee. But the panopticon aspect here was designed and intrusively did control the dialogical aspects of letter-exchanges by reducing such exchanges to a bare and censored minimum. A result is that the letter sequences referred to in quite a few letters were in fact often not the sequences experienced either by the addressees or by Mandela himself, because ‘interruptions‘, removals of letters as well as excisions of sentences or paragraphs or passages, were imposed but not told about by prison authorities.

By nature and definition, in general letters are written in order to be dispersed and the writer of letters will never have seen them altogether. These letters are an interesting exception to this general rule. Because of his writing practices in the context of imprisonment and keeping handwritten copies of everything, these letters would in fact have been seen as ‘the prison letters of Nelson Mandela‘ by Mr Mandela himself. But were they just left on a shelf in his prison cell? Or did he read them over? If so, was this to enhance the vagaries of memory with the certainties of words on paper? Or to remind him of people and places and feel less disconnected? How did his letter-writing style change over time, and did it change or perhaps were the specifics of who he was writing to more important?

This is an edited collection with an antecedent ‘collected’ existence, indeed a number of them. Because of the surveillant gaze and its ‘grind them down, cut them off, remove them from any outside interest or influence’ intentions, many of these letters in their original forms (i.e. not transcribed by Mandela into notebooks, not typed up with excisions silently covered by prison officers) were in fact already collected by the prison authorities even before they were collected into archives in South Africa and elsewhere, and long before the editor of this present edition went about her work. Mr Mandela composed his letters as a collection, the prison authorities produced a collection of them including of typescripts of those that were sent on, the people who received the letters that they did kept them in a collected form, formally constituted archives later collected them, the editor collected them and transcribed, or re-transcribed those that had already being transcribed, in a form suitable for publication. The sedimentation effect is tremendous. And here we are, readers of this excellent book, near the end of the process and adding our own small contribution to it.

This edition of Mr Mandela‘s prison letters is certainly an important milestone in encouraging a more detailed investigation of the ideas and practices articulated by him during his long years of imprisonment and its imposed curious public/private/organisational frame that surrounds these writings. It is, as befits such a statesman-like figure, in some ways a curiously old-fashioned enterprise. This is an excellent print edition and it provides an equally excellent editorial apparatus that will enhance the experience of readers. But on the one hand, there is no point of access to the manuscript or typescript ‘originals‘; and on the other, there are no digital forms of the transcribe letters available to permit much more detailed searching and use. Therefore it is to be hoped that a Kindle edition will arrive soon. But in the meantime, there is of course this most welcome contribution to the Nelson Mandela secondary literature to read. The editor is to be congratulated on her excellent work.

Sahm Venter ed 2018 The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation/WW Norton & Company. ISBN 978–1–6 3149–1 17–7

Last updated: 14 July 2018