Instantiations and ontologies: Part 2 of the Henry Francis Fynn letters

This is the second instalment in a two-part blog concerned with thinking through how to work on the letters in the Henry Francis Fynn Papers. The contents of Part 1 will not be repeated here, but can be accessed and read by clicking the live link.

Working on the letters of Henry Francis Fynn (1803-1861), which were written to as well as by him, raises some complexities – what and where exactly are ‘the letters’? There are three instantiations of them: in two archives, in three locations within these, although in a formal sense there is just one ‘real’ collection of letters. A number of issues arise from the existence of this conjunction of linked but ontologically distict sources, in particular concerning what ‘the trace’, the founding source, is and in what ways this might change.

Instantiation 1

There is an extensive typed inventory of the Henry Francis Fynn Papers in the Pietermaritzburg Archives Depot, with the Papers being ‘the’ collection of Fynn materials thrown up when searching for archival sources.

The Inventory provides a detailed overview of the contents of the collection, the Papers. Among other information, it contains an itemised list of its letters received and dispatched. These are in date order together with the name of the letter-writer (which, as noted, is not always Fynn ) or the recipient. Two entries are:

Received…

R Southey 5 1 1848 [From Richard Southey to H Fynn, 5 January 1848]

…

Dispatched…

Thomas Jenkins 24 6 1849 [From Henry Francis Fynn to Rev Thomas Jenkins, 24 June 1849]

As can be seen, the information in the Inventory is in effect a massive list that indicates names and dates but is otherwise empty of content. By being so it highlights contributors and flows of letters over time without these being masked by the typically abundant specific detail of ‘actual letters’. It picks these things out and makes them immediately visible. It isolates these aspects of temporality and contributor, with the result that in a way there is no reader, for there is no content, but instead more of an enumerator who counts the two elements that compose the extensive list provided.

Rather than coming across as denuded of textual content, the effect is of the reader being presented with something that is replete with numerical information. The immediate response is: Set to work! Use the list! Count! So what might this work consist of and why carry it out? The things that can be done are perhaps rather basic but are nonetheless important because they can give rise to insights into the structure and organisation of the Fynn letters and what these add up to in conceptual terms. They include:

How many letters? When do they start and when do they finish?

How many letters are there per letter-writer? and how does Fynn figure in this?

When do letters to particular people, the addressee or recipient, start and when do they end?

What comparisons can be made in looking at the flows of letters of different people over time?

What such counts provide is ingress to seriality and longitudinality, that is, the patterning of repetitions and flows over time. What they add up to is a schematic overview of the figurational aspects of the letters in the Fynn Papers: who and when at what particular points in time, and changes in this over time. This is why it is helpful to use the schematic information in this Inventory: it opens up something very complex and with crucial changes occurring in it over time, but does so in a graspable and pared down way.

Instantiation 2

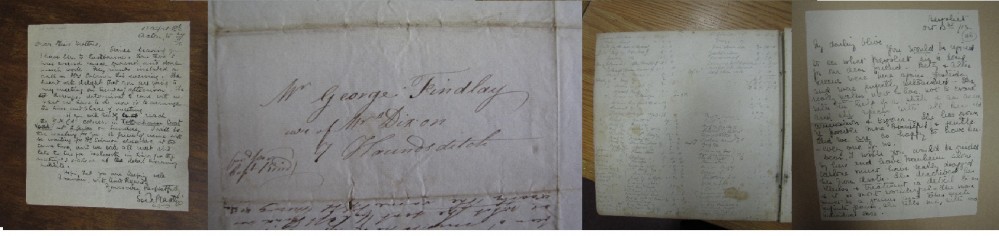

As noted above, the Fynn Papers in the Pietermaritzburg Archives Depot are ‘the’ collection of Fynn materials, with the hundreds of letters it contains being the manuscripts written at the time. Opening its boxes and folders reveals the enormous and indeed overwhelming content that is involved in confronting these c600 items, many of which are considerably more than one item, in the sense of being composed by a number of separate sheets of paper.

The ‘actual manuscript letters’ are ordered but of immensity in terms of the researcher or reader being able to grasp their character and import: there are so many, and they are in so many different handwritings. Their content in a way erupts from their archival containers as a feast for the eyes and as an assault on the mind. The eye followed by the mind catches names and words and phrases: the widow of Capayi, aggressive movements, circulate reports, Faku, go soon, d’Urban, bring it, his children, their intention, Panda insisted, …. This list could go on almost forever, some 600 letters-worth of words and names and phrases in different and sometimes contending writing where the ‘same’ names or words may be spelt or simply look very different ad inscribed by different people. Grasping their order and their import both individually and as a set is no swift or easy matter, but also and perhaps more significantly the content overwhelms and overwhelms and overwhelms.

The letters and the plenitude they represent may be considered to be graspable because they can be literally grasped, that is, held and read. But they are of great fragility and many are encased in sealed protective folders and cannot actually be grasped without imposing considerable wear and tear on the epistolary items within. The plenitude erupts and assaults. Then assault is edged out by bafflement – all those specific particularities, but which cannot be fully read and grasped because the fragilities of these traces mean that grasping leads to damaging or even to destroying, and anyway there are so many of them.

The ‘actual letters’, then, burst out of their containers – wrappers, folders and boxes – to broadcast their many exacting particularities; but their multitude of specifics also baffles and returns the gaze to gaze, to surface matters rather than to attentively reading narrative detail. Also their trace ontology invites increasing familiarity by calling a name – Dear Col Smith, Dear Mr Jenkins, Yours HF Fynn – which the researcher/reader strains to follow; but it also inhibits closeness through the damage that can be done by contact. Overall, ‘the latterday reader’ is beckoned but also pushed away, and ‘the letter-writer’ is emphasised rather than the reader while at the same time vanishing into the detail jostling for attention.

Instantiation 3

The Killie Campbell Library in Durban has within it another Fynn collection. This has a different ontological character from what has been discussed so far about the Fynn Papers and can best be seen in meta-terms. Its contents are variously a draft typescript by James Stuart regarding his wider work when editing Fynn’s diary, typescripts of the diary and Fynn’s letters, Fynn’s evidence to an 1852 Native Commission, the script of an interview carried out when the Fynn papers at the Killie Campbell were opened in 1946, and some other items, including some manuscript originals.

On the surface the contents of the Killie Campbell collection look like they were produced by or came from Stuart, the initial editor of the Fynn diary who was later joined by Malcolm, although the dates on some items seem out of synch with this. However, what is in Killie Campbell are clearly predominantly meta-versions, as typescripts of a biographical account, a diary, letters, evidence, an interview, with some associated manuscript originals. But, focusing on the typescripts of the letters specifically, what does this mean and what results in terms of ‘the trace’ and its ontology?

On the surface the contents of the Killie Campbell collection look like they were produced by or came from Stuart, the initial editor of the Fynn diary who was later joined by Malcolm, although the dates on some items seem out of synch with this. However, what is in Killie Campbell are clearly predominantly meta-versions, as typescripts of a biographical account, a diary, letters, evidence, an interview, with some associated manuscript originals. But, focusing on the typescripts of the letters specifically, what does this mean and what results in terms of ‘the trace’ and its ontology?

‘The trace’ is generally assumed to refer to ‘originals’ where these exist, and a close proxy for them where they do not. It is clear that the Fynn letter transcripts are not ‘originals’ and that the manuscript letters exist elsewhere, in Pietermaritzburg. But the transcripts are not ‘just’ copies either, for someone other than their first or original writer has been at work in producing them, in the shape of a second writer busily following the written words but doing something else as well.

This something else is that the second writer here is an intermediary, a go-between linking readers and original writers. The activity involved is interpretive because their reading and re/writing necessarily includes deciding on handwring issues, mistakes and omissions and so on, the whole range of editorial interventions in producing a ‘readable’ text, with the inbuilt presumption that third parties will read the result of this activity. It is in addition transmutational, because it results in shifting a letter from one form or ontology to another, from a basically private communication between the letter-writer and their addressee, to one with public third-party aspects, and also from one sub-genre to another.

What is produced is regularised tamed content, with any issues removed or ignored in achieving a smoothed over text which third-parties can easily grasp and read. Editorial violence has been involved in this, in executing interpretational decisions regarding the what and how and why the writing of the ‘original’, although the convention is that little sign of this appears on the surface and so for practical purposes can be ignored by third-party readers. The smoothed out text of a transcription achieves a practical balance between following the name – the letter-writer, the addressee – and detail – the widow of Capayi, aggressive movements and so on. But what it loses sight of is the actual messy forbidding baffling manuscripts, and the often fierce tussles involved in coming to know them.

There is also something more going on here, concerning the character of ‘the trace’ itself, or rather what ‘the trace’ becomes. If the Inventory delivers a shorthand or proxy for the structure of the Fynn collection of letters, and the manuscripts letters exist as a baffling cornucopia which throws up and highlights the content, a set of transcriptions seemingly provides both structure and content and in some kind of harmony. The Inventory and the transcriptions are imperfect shortcuts, and the manuscript letters are ‘the trace’. But this is only seemingly, because at the same time transcriptions have a strong seductive aspect – they are not ‘the thing itself’, but they are close enough to be seen as the portal through which work on the thing itself can be progressed.

All transcriptions exert this seductive appeal, and their siren song is loud and entrancing: why struggle for hours with just short passages of a manuscript when many pages of transcripts can be read in minutes and then later perhaps checked against the originals? This is not an entrapment, the seduction is real, there is indeed the delivery of something graspable and accessible. However, this not archive research without tears or fears, but an activity which is different in kind rather than degree. This is because that ‘later’ regarding the originals is infinitely deferred or perhaps never on the agenda. It is likely, more than likely, that the large majority of readers of the letters resulting from transcription projects such as, for instance, the Olive Schreiner Letters Online, both start and stop with the transcriptions, even though in this particular case there are in-built mechanisms to push readerly activity back towards whole Schreiner letters, manuscripts, collections and archives.

Such a ‘the transcripts are the thing’ response cannot be dismissed as simply recalcitrance or lack of awareness, not least because doing so would ignore what is happening to ‘the trace’. Such an anticipation or prefiguration of the trace is of course not new and it exists wherever there has been an editorial intervention with its interpretation and transmutation, and so it is associated with the very first papyrus editions of letters as well as current electronic ones. What is new is the paradox of a vanishing or bracketing of the editorial function in recent advanced technology endeavours, the very medium which could most easily give expression to them. It could most easily do so including because its capacities can include more material and editorial commentary with only incidental marginal cost, Rather than paper, postage and reproduction, its costs are intellectual and ethical: the editorial I did it like this, because, resulting in…

Putting this consequential vanishing on one side, it may seem to be the case that ‘transcription plus digital image = the thing itself’, the trace rejuvinax because made available to all who have a computer at their disposal. But as a moment’s thought indicates, this is actually a two-dimensional parallax which is context bereft and accompanied by interpretational violences which have been exerted although they are politely unmentioned. Its displacements are that it loses time, substance, seriality, provenance, and does so in a way by definition because of characteristics of the representational medium involved.

What is also lost but not by definition is elision of the interpretational and transmutation of activities of the editorial function, for this often occurs because editors are as entranced by the possibilities of the medium as readers and fall for the seduction effect in a major way. The tacit view for many e-editors seems to be that if all the bells and all the whistles are provided, then the result is as good as the thing itself, and better in the sense of being available complete, with all the scattered letters of X or Y brought together and presented to readers. And – and this must be stressed – for the now immensely large number of people engaging with epistolarity in all its guises through such a ‘secondary’ electronic medium, there is no secondary about it and for all practical purposes ‘the trace’ is now its representational form.

‘Please send me all the Schreiner letters’, I was asked a few months back, with the researcher concerned having little truck with my explaination that these were scattered in many collections and archives world-wide. For them the letters were what the Olive Schreiner Letters Online provides in a dispersed form across the different sections of the OSLO website, and what they wanted available were the letters complete and undivided delivered to their desk in one tidy folder. This is of course where electronic projects came in the door, to provide something complete and undivided as a meta-collection re-representing the trace. However, for many the conceptual universe has subsequently shifted on its axis, with the resulting parallax positioning the components of this formerly meta-incarnation as (though) baseline traces.

Heterotopia?

So where does this discussion leave ‘the trace’ and the related matter of WWW work on the Henry Francis Fynn letters? The discussion is unfinished, the debates are ongoing and necessarily so because developments in technology and representational media continue apace; and the points raised here are not a matter of good and bad because issues arise in working with all of the possibilities for engaging with letters. That being said, there are some broad observations to be made.

The technology genie is now out of the bottle and is not going to be put back in. The consequently bifurcated character of ‘the trace’ has to be grappled with, at the same time that the general vanishing of the researcher and editor and their work in producing-versions needs to be protested and made present in new epistolary ventures.

In relation to the Fynn letters, once the Inventory and transcriptions are known about then there is no turning back. Like it or not and willingly or not, ‘the trace’ here becomes both the manuscripts and also these two other related meta-forms, the transcriptions especially. But as with triangulation generally, these are less three different ways in which the ‘same’ thing appears and can be compared, than they are three different forms or genres which share an object at the core – some observations by one person to another about people and events of times gone by – but represent or re-represent this in radically different ways. Three ontologies, not one and two proxies.

As I have argued across various published work (see website below), an epistolarium (all the letters written by someone, and where possible also those sent to them) develops characteristic writing practices, in particular where there are long-term correspondences involved. These include an emergent frame of reference, favoured topics of discussion, meaningful turns of phrase, avoided subjects and so on. And while letters remain wedded to their referential base of the things that happened and the people who did them, these writerly aspects also lend a fictive rather than fictional cast to what is inscribed and read.

For Maurice Blanchot (1955), all fictions have strong heterotopic aspects. That is, these are representational worlds or spaces that have their own temporal orders, casts of characters, rhythms and plot motifs, ethical concerns and so on. A similar argument can be made about the fictive elements of epistolarity, and future work of the content of the Fynn letters will discuss the heterotopic aspects of the three different sources including around how they orientate to or re-orient ‘the trace’.

References

Maurice Blanchot (1955) The Space of Literature University of Nebraska Press.

Liz Stanley web page http://www.sociology.ed.ac.uk/people/staff/stanley_liz

Archive sources

Fynn Papers Inventory, Pietermaritzburg Archives Depot, Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa.

Henry Francis Fynn Papers, Pietermaritzburg Archives Depot, Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa.

Henry Francis Fynn Collection, Killie Campbell Library, Durban, Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa.

Last updated: 6 January 2017