Here it ends with my pen, but not my heart

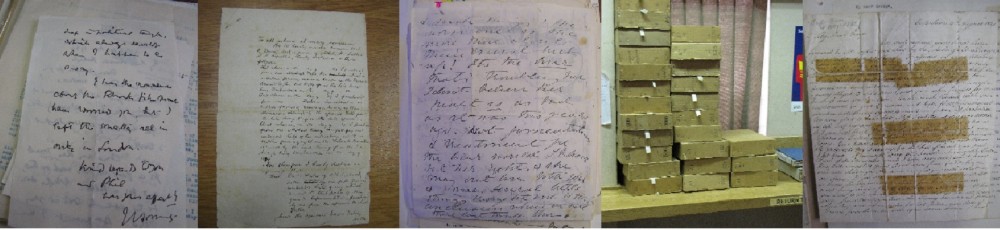

At the end of June 1902, the South African feminist writer and social theorist Olive Schreiner wrote to her sister-in-law Fan a letter which concluded with ‘Good bye. “Hier eind it met mijn pen, maar niet mijn hart.” [“Here it ends with my pen, but not my heart.”]’ (OS to Fan Schreiner, 30 June 1902). This is an ending which is not an ending – Schreiner’s pen stopped on the paper, but what produced the letter, which was her and Fan’s loving friendship, continued.

Fan Schreiner was of Boer (later Afrikaner) extraction and the old-fashioned Afrikaans saying that Olive Schreiner uses operates on a number of levels. It teases Fan by ‘out-Boering’ her, for she came from a sophisticated urban middle class background and could speak Dutch but not, unlike Schreiner, the early ‘back country’ form of Afrikaans used by ordinary folk. It indicates Olive Schreiner’s respect for the traditional Boer farming way of life and elliptically references her and Fan’s shared political views regarding capitalist imperialism in southern Africa. It gives expression to their epistolary exchanges generally as well as this letter in particular being the sign of a close loving face-to-face relationship, for it had been written and sent in circumstances of temporary interrupted presence, rather than the ‘absence’ that much epistolary theory has hooked letter-writing to.

Schreiner’s letters frequently play with, traverse or undermine the ends of ‘the letter’ as a form or genre, in troubling the conventions often seen to define what ‘a letter’ is. Sometimes her letters can take ‘other’ forms, by for example being written in the form of a telegram or an advertisement. Sometimes they mix ‘different’ genres, for her letters can both address and engage with the intended recipient and at the same time, for instance, be polemics or theoretical inquiries (and conversely, her polemics and theoretical treatises often directly address readers). Sometimes they may pay brief lip-service to the conventional form of ‘the letter’ by starting with an opening address to a named person and finishing with a closing signature, but otherwise taking the form of published statements syndicated in newspapers. Sometimes they may have no direct address and no signature, but still meaningfully and recognisably (to their recipients as well as to readers now) communicate in representational form from one person to another in circumstances of absence or interrupted presence, the basic feature of ‘letterness’. And sometimes, as here, they may halt, but they don’t end in a meaningful sense.

At the same time, however, these complexities of course depend on ‘the letter’ having a recognisable conventional form, although the specifics of this will change over time. What I call ‘letterness’ – playing with, undermining or abandoning this or that definitional aspect of ‘the letter’ and its conventions in order to better communicate between a writer and their reader and give expression to epistolary intent – needs, requires, ‘the letter’, or rather the existence of some prevailing conventions concerning such.

Last updated: 6 April 2018