Bombardier John I Hemming

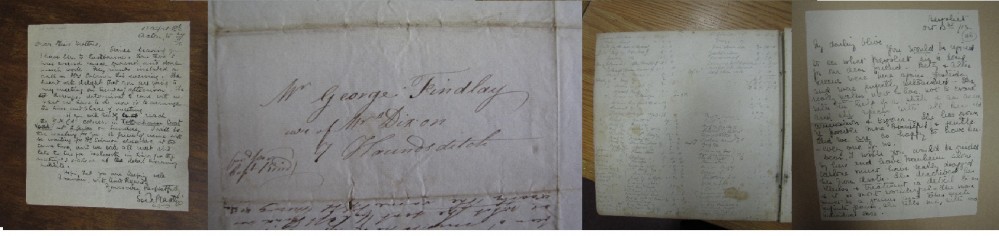

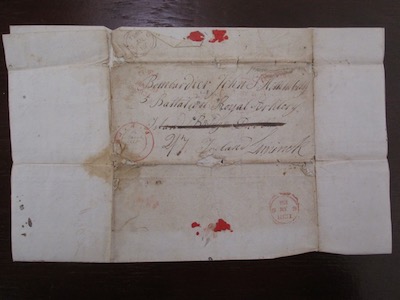

The three previous Friday blogs are concerned with page 1, page 2 and page 3 of a letter written by Joseph Hemming in Upper Canada and sent to his brother Bombardier John Hemming in Limerick, Ireland. The letter begins, ‘I tak up my pen’. This week’s blog continues with page 4, which was folded around the others, providing both a cover and a kind of envelope. As the photograph shows, it has John Hemming’s name and address and the marks of a seal on it. As a consequence of its function, it also bears the signs of wear and tear produced as it travelled the oceans.

The three previous Friday blogs are concerned with page 1, page 2 and page 3 of a letter written by Joseph Hemming in Upper Canada and sent to his brother Bombardier John Hemming in Limerick, Ireland. The letter begins, ‘I tak up my pen’. This week’s blog continues with page 4, which was folded around the others, providing both a cover and a kind of envelope. As the photograph shows, it has John Hemming’s name and address and the marks of a seal on it. As a consequence of its function, it also bears the signs of wear and tear produced as it travelled the oceans.

Can this final sheet be looked at in a way that reveals more than just these immediate features?

The splits in the writing paper and missing slithers which make parts of the content of page 3 difficult to read are of course also visible on the address side. They show clearly how the paper has been folded. While the letter was en route to its destination, what would have been visible are the middle panels shown in the photograph, with the two outside ones overlapping each other after folding. They are noticeably dirtier than the inside sheets. They also bear a seal and the middle panel has on it the name and address. The remains of the seal are shown in the cracked and splintered red wax; close examination suggests it was nothing very fancy, just a plain piece of sealing-wax to prevent the pages coming undone and prying eyes reading the content. There is also in red ink a ‘Paid’ stamp to show that the cost of postage had been already paid. Also there is a written ‘Paid’ and what looks like ‘3N’ associated with it. In the 1830s, the prevailing currency would have been dollars in North America and pounds and shillings in Ireland, so what the ‘N’ refers to is unclear.

This sheet of the letter when folded would have been dominated by the name and address on it. It is addressed to ‘Bombardier John I Hemming 5 Batt Royal Artillery’ in what is definitely Joseph Hemming’s writing. It is also notable that, by comparison with his functionally literate letter-contents, the envelope is precisely written with ‘proper’ spelling. Artillery regiments were concerned with the heavy weaponry of an army, such as cannons and ‘field guns’ pulled by horse. ‘Bombardier’ is a promoted rank specific to the artillery, and it is the equivalent of corporal. The address was originally written as ‘Island Bridge Dublin’, which was presumably where John Hemming’s 5th Battalion was stationed before it was dispatched to Limerick, while the Dublin line has been crossed through and Limerick inserted in a different handwriting.

There are a number of postmarks representing different points on its journey, although not all of them are readable. The letter is internally dated as 8 December 1830. One of the postmarks is illegible, while another is partly handwritten and difficult to read but is likely to be ‘14 Mar 1831’, while a third is probably ’29 Mar 1831’ and two more are dated ‘9 My 1831’. Other information on the stamps is too faint to read but is likely to have indicated postal offices. It seems likely that John Hemming received his letter soon after 9 May 1831, around four months and one week after it was posted – and remembering that this is still the time of sail rather than steam in crossing the oceans.

What can be gleaned from the postal information, then, is quite limited, although it adds to the sense of a long and difficult journeying for the letter and the care that was taken in its writing and its direction. It also quite literally shows that John Hemming as well as his brother was on the move.

PS

There is no PS to Joseph Hemming’s letter, but there is to this discussion of it. This starts with what conclusions may be drawn about it, for at first sight, this letter may appear to have little or nothing to do either with South Africa or with whiteness. But this immediately gives way to the realisation that it is in fact connected with the very essence, being written at a pivotal point near the start of those extraordinary movements of people that were the mass migrations of the middle and later 19th and early 20th centuries, predominantly but not exclusively of white people of European origins, and which transmuted imperialism into colonialism. For those like the Hemming brothers, things were a-changing and if they weren’t then they soon would be. Should they stay or leave? If leave, then where to go, and how? They were after a different kind of life, one which could provide them with opportunities that they probably wouldn’t have if they stayed, and which previous generations had certainly not had.

And there the tale told by the letter that Joseph Hemming wrote to his brother John ends. However, there is more to add, gained from other letters and documents that are part of the archival record.

John Hemming arrived in South Africa as part of the British imperial presence, while he stayed there as a settler colonialist. His army career blossomed and he was promoted to sergeant. In 1844, he was released from the army with the special agreement of its commander, Sir George Napier, who was also at the time Governor of the Cape. This was to allow him to be appointed to a new post, working for the then Colonial Secretary, John Montagu, as a Cape Town tax collector [see http://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/traces/from-john-montagu/]. And what then?

John Hemming appears in brief mentions in later reports, described as a stalwart of Cape Town white public life. His children were perhaps born and were certainly largely raised in Cape Town and were South Africans through and through with no sign of any remaining allegiance to either Ireland or Britain. His son Robert, later a key figure in founding the Johannesburg Public Library, married Alice Schreiner, the second daughter and third child of Gottlob and Rebecca Schreiner. Alice’s youngest sister was the writer and social theorist Olive Schreiner.

Alice inherited the Schreiner family heart valve problem and many of her children survived only for short time, while she herself died suddenly when still a young woman. After her death, the surviving children – Effie, Wynnie, Guy, Elbert – were adopted and raised by Alice’s younger sister Ettie and also by the woman who worked as their Nannie. She gained public fame as Sister Nannie, with Ettie’s support running a series of homes for vulnerable black and coloured young women. Her formal name was Anna Tempo, the daughter of freed Mozambique slaves [see http://www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/traces/whiteness-now-you-see-it-now/]. Ettie Hemming later married Arthur Brown, whose father John was a white LMS missionary and whose mother Eliza was part Khoisan with a family lineage including two of the most famous and radical LMS missionaries of their day, the father and son James Reads.

Last updated: 20 September 2018