Analysing a letter in detail

On 15 January 2015, the most recent period of WWW fieldwork to date, I wrote a blog that sets out how to skim through and get to know the bones or structure and main concerns of an archive collection very quickly, while also making a basic record of all its contents. It can be found in the blog of 18-24 January ‘Recording archival documents at volume‘ (part of Puzzles, Problems & Possibilities). This present blog is a companion-piece, because focused on how to analyse a letter or document, one of them, in considerable depth. It provides a simple and hopefully useful methodology for doing this.

Letters are ‘documents of life’ – they are not researcher-generated but exist as a part of ordinary social life. However, they do not ‘speak for themselves’. They are produced in artful ways, putting across a particular message in a particular ‘voice’, and intending (although not necessarily producing) a particular desired effect on their reader/s. Consequently they need to be treated in an inquiring and analytical way, including by recognising their temporal aspects. There are different kinds of documentary analysis, with the approach adopted here involving ‘re-reading’, that is, reading in an analytical way against the grain of how its writer has structured and intends a letter or other document to be read and interpreted.

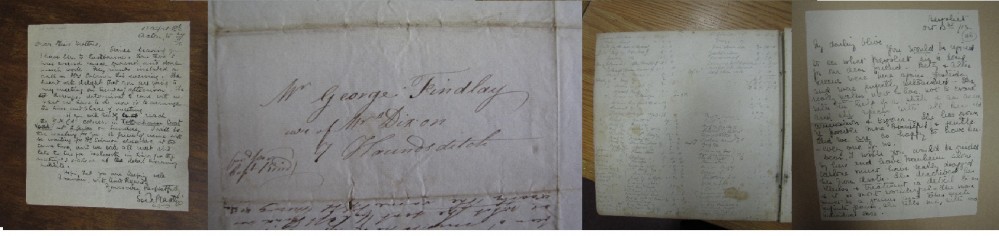

The basic elements are to focus analytically on: context; pre-text; the text and its meta-data, content and structure; post-text; and the new context that subsequently arises. This is explained below by analysing the text of a document – how should it be viewed, as a letter or something else? – which appears in the WWW Cabinet of Curiosities page entitled ‘A letter is a letter is…‘. A transcription of it is as follows:

Offices of the Swazie Nation

Swazieland Feby 8th 1893

This is to certify that David Forbes Esq of Athole New Scotland is the registered holder of an undivided 3 / 8 (three-eight) interest in and to a certain grant for unreadable ^grazing^ farming, timber and other rights on certain portion of Swaziland known as the Mananga Grant and the title thereto is ?clear and unencumbered in the Registry Books of the Swazi Nation

Wm Penfold

for Theo: Shepstone

Res Adviser & Agent

Swazie Nation

[William Penfold for Theophilus Shepstone jnr, 8 February 1893, Swaziland; Forbes Collection, NAD Pretoria.]

Context1

The broad context is the ‘scramble for Africa’, European colonisation, the discovery of diamonds and gold and other minerals, and the creation and exploitation of black labour, with significant literatures on these. The specific context is the period from 1886 to the later 1890s, when there was a ‘concessions rush’ in Swaziland (and in other areas too), with white prospectors and miners jockeying to gain access to land believed rich in minerals, including tin and coal as well as gold. The Swazi king Mbandzeni was overwhelmed by the inrush and made land grants pell-mell. After he died in 1889, his mother the Queen-Regent, Tibati Nkambule, and the Swazi Council of indunas employed Theophilus (known as Oppie) Shepstone jnr as a Resident Agent, with part of Shepstone’s role to ensure concessions were systematically authorised and managed. William Penfold was Shepstone’s deputy and secretary. On one level just the agents of the Swazi rulers, in practice both men pursued economic self-interest and were disliked by (some) other whites for their veniality and incompetence and because farmers among them saw their stock-grazing concessions being usurped by minerals claims.

Pre-text

The immediate circumstance producing the Shepstone document was the anticipation of a new rich mineral discovery, and the role in this of various members of the Forbes family, including David Forbes snr, his brother James Forbes snr and David’s sons Dave jnr and Jim jnr. David snr was primarily a commercial farmer in south-eastern Transvaal, close to Swaziland, and James senior a prospector involved with others who either shared or were in competition for the concessionary interests being advanced for Swazi recognition. As well as the Swazi elite, the Resident Agent had to deal with a (white) Legislative Council of mainly prospectors and miners, as well as many concessionaires including farmers with competing interests, with the document one of many examples in which Shepstone constructed the semblance of legalistic order in a situation where his motives and practices were (rightly) suspected on all sides.

Text

Meta-data: Detailed information as to ‘who, when, where from, archive location’, where relevant also ‘to whom, where to’, and also a unique reference number, forms the ‘meta-data’ of research records and is crucial for finding particular documents so that, for example, any specific document can be easily retrieved from many thousands by searching on names and dates. The Shepstone document begs questions about some meta-data. Firstly, which David Forbes, father or son, is invoked? The presence of ‘Esq’ and absence of ‘Jnr’ suggests the father; the absence of mining and the presence of grazing and timber suggests the son. Secondly, while on the surface an official certification with a seal, the exemplar also has apparent ‘letterness’ features: it has an address it is written from, a date it was written on, signatories, and also ‘address’ in the sense of being directed to a (unspecified) person or persons about the matters it certifies. Meta-data for search purposes needs to be accurate and certain; but in practice puzzles like these frequently remain.

Content: WWW’s research records the main points in the narrative content of a 1 in 5 random sample of all letters and other documents read, plus others of interest. A more detailed consideration is reserved for documents seen as particularly interesting, of which the Shepstone example is one. It has some strong official overtones, with a printed heading and concluding with an official sign-off and seal. Also it is presented as in itself a certification of, if not ownership, then the ‘holding’ of land in a ‘certain area’ for specified purposes. These involve activities on the land’s surface, although the vague ‘other rights’ raises additional possibilities. At the same time, using context and pre-text matters to read against the grain, for anyone ‘in the know’, as David Forbes (both father and son) and other interested parties certainly were, the complex and increasingly fraught character of relationships between the Agent and the ‘Swazi nation’, the Agent and the different groups of concessionaries, the concessionaries and the Swazi ruling elite, would have been apparent, as would that officialdom was far more uncertain than this paper proclaims. Also its authority is mitigated by reference to the Registry Books, indicating that its certification actually depends on what these contain, while other slantwise aspects that re-reading brings to attention can be seen regarding the more structural features of the document.

Structure: The ‘voice’ in which the document is written is an authoritative one; it certifies and it does so presumptively on behalf of ‘the Nation’. Authorial location is removed (‘it is certified’, no one does this). However, it ends with signatures that are not of ‘the Nation’, but Penfold (who is he? this is not stated, indicating an in-group readership who would already know this) signing on behalf of Resident Agent Shepstone. Reader positionality here is one of reception and non-response, but there are also signs, like not stating Penfold’s position, that notions of readership and address have actually been a factor in the organisation and tone of the document. Other aspects of this come to attention through re-reading, for close attention shows that the claims to certificatory authority rest on two externalities: the implied synonymity between the Swazi Nation and the Resident Agent, and intertexual references to the Mananga Grant and to the boss text of the Registry Books.

Post-text

It is only rarely that the direct effects of historical (and indeed contemporary) documents can be gauged, for information enabling this is usually no longer available. However, many archive collection contents are organised in temporal order, and anyway a database or Virtual Research Environment (a bespoke online platform for data-management and aiding analysis) can easily sort research records in this way, so ‘what came next’ can often traced even if the direct impact, if any, of a document cannot be known.

Regarding the Shepstone document, other letters in the Forbes collection provide quite detailed information about the course of events. The dissatisfactions of the Swazi ruling elite with the Shepstone Residency increased, because of its double-dealing and corruption. The ‘young Queen’, Labotsibeni, the mother of Bhunu, king-to-be but still a minor, gained political control. Shepstone was removed from office, with a tussle over ‘the Books’ resulting in these being audited by the book-keeper of a firm employed by the Swazis. Also, with the support of Dave Forbes jnr, the Swazi rulers sent a delegation to Britain requesting assistance in resisting attempts by the South African Republic or Transvaal to take over Swaziland. Other Forbes letters relate to these matters and show the ‘one thing in the midst of another’ character of unfolding events.

Regarding the direct concern of the document, the part-concession for some rights (but not others) within the Mananga Grant, behind this lay Mbandeni’s concessions of land many times over to different people for the same or contradictory purposes. Being close to the Swazi rulers and advising against this policy, the Forbes then gave way and gained a number of concessions themselves. Later, many such ‘interests’ were contested by contending interests and were not legally sustainable. In the case of a concession to Dave jnr for grazing and timber in the area of Forbes Reef (which might be that specified in the document), the coal mine’s later owners established that these surface rights were null and void.

Context2

Social life is always in media res, always in process, and the flow of wider events affecting Swaziland continued, as well as the small part of them alluded to under the ‘Post-text’ heading. A London Convention of 1894 gave way to Transvaal designs on Swaziland as a source of cheap labour by assigning it a protectorate role. However, in 1910 and against the demands of the incoming Union of South Africa Government formed that year, the Protectorates of Basutoland [Lesotho], Bechuanaland [Botswana] and Swaziland retained their independence. The Forbes’ Transvaal farming and Swazi mining and other interests became more diversified, especially after the death of James Forbes snr in 1896.

Issues

There are important interpretational matters underpinning this discussion worth noting. While taking particular shape in the WWW context, these have general aspects.

‘The thing itself’ and referentiality matters: Almost all the data that social researchers work with are not ‘the thing itself’, but rather representations of this that are partial, fragmentary and emanate from particular viewpoints. What this raises is the need to avoid the referential fallacy of straightforwardly concluding ‘it was so’ from any document, while also still recognising that there was a past in which real things happened and the remaining traces reference this, albeit in complex ways which need to be considered against as well as with the grain.

Identifying the topic: Social life rarely comes in discreet chunks labelled ‘gender’, ‘class’, ‘the Schleswig-Holstein question’, ‘whiteness’ or ‘the scramble for Africa’; and as shown, the latter was greatly complicated by the particularities of times, places, events, persons and interests. The word ‘whiteness’ does not appear in the Shepstone document or associated letters and has be interpreted by reference to the activities being orchestrated or described or commented on (Context 1 and Pre-text), the ways the various documents represent these matters (Text/intertexts (including associated texts) and Post-text), and the specific and broad outcomes (Post-text and Context2) that have been traced out. Succinctly, while an analysis of the specifics of the document goes quite a long way, such analysis is a support to interpretation and not the totality of what is involved.

What it means: The point of research, the reason it is carried out, is interpretation and thus an assessment of overall of what things add up in the creation of new understanding. At the same time, interpretation in the sense of drawing conclusions should not be done prematurely. Also interpretation is typically an iterative procedure of going back and forth between conceptual, methodological, analytical and interpretational matters and working the links and connections across the relevant data until something making sense of all these eventuates. To a large extent this requires having a feel or a ‘nose’ for scenting what is interpretationally interesting. However, this is not magic, but results from close familiarity with the data and so is a matter of attentive practice.

But what IS the Shepstone document? Letter or what? Answers in an email please!

Last updated: 25 April 2015