A Schreiner Cabinet

Deborah Lutz has produced something extremely interesting in her 2015 The Brontë Cabinet – Three Lives in Nine Objects. This explores the intertwined lives of the Brontë siblings by reference to the material objects she writes about, which stand for different aspects of their lives, activities and circumstances. Her purposes are strongly biographical, with her introduction positioning these things as powerfully raising the realities and facticities of their lives, as resonant biographical objects that help elide the separations of time etc existing between us and them. While not buying into her rather resurrectionalist view of the power of biographical things to conjour up past lives or aspects of them, Lutz’s discussions are well-grounded, astute and throw interesting light on many aspects of the intertwined lives of the siblings. Her book also raises the thought that it might be interesting to think about other lives in proximate terms, and in reading it my mind turned to what an Olive Schreiner cabinet of key biographical things might look like. The result is the set of ten such things now briefly outlined.

The baptismal record: This is a spare entry dated 4 November 1855, recorded in the handwriting of J. Ludorf, of Olive Schreiner’s birth on 24 March that year. It immediately raises the complex and sometimes tragic family histories which preceded her arrival in the world, with her name as Olive Emily Albertina containing echoes of the names of three siblings who had died as infants or in childhood. Having missionary parents was both a plus and minus for the Schreiner children. Olive’s knowledge of both the Old Testament and the New enabled her to outquote the most vociferously dogmatic of Christians in arguments and she relished the rich source of commanding language she had gained. The narrow punitivenes of her parents was not the only negative aspect, but it was one of them, while her own kindly tolerance combined with firmly stating her own views was a productive later result. Early on, she rejected Christianity and also resisted using the language of God and religion, but later reverted to doing so because it was an idiom which people understood and responded to in relation to ethical and political matters.

Photograph of the young Olive: This is the photograph used on the cover of The World’s Great Question, a collection of Schreiner letters focused on her analytical engagement with South Africa edited by myself and Andrea Salter. Schreiner here is young and confidently stares towards the camera with a look that rejects the dissimulation of an aside glance in favour of meeting full on the gaze of the lens turned upon her. Her look is both enquiringly and somewhat disconcerting. There are quite a few surviving photographs although relatively few of the portrait variety. They are perhaps more misleading than helpful, though, as a few frozen stilted monocrome moments, out of the myriad of moving multicoloured eventfulnesses of the life lived.

Her baby’s coffin: This lead-encased coffin was a constant presence in Schreiner’s life from the death of her day old baby (a daughter who was it seems never named) in 1895 onwards, but is seen in a photograph only after Schreiner’s own death. As was not unusual in South Africa at the time, the coffin was buried on Schreiner land and it was moved when Schreiner and her husband moved from place to place, remaining in De Aar with Cronwright-Schreiner when Olive Schreiner left for Europe in 1913. It is shown with the coffins of Olive Schreiner herself and her much loved dog Neta in a photograph taken on the day when all three were moved to the stone sarcophagus on the summit of the Buffels Kop mountain near Cradock in the Eastern Cape where they were entombed. Schreiner often movingly mentions her daughter in letters and her death was one of the bonds she felt existed between her and WEB DuBois when she read his essay on the death of the first born (his son) in his Souls of Black Folk.

Tucker’s asthma mixture: Schreiner developed asthma, probably the result of chronic acute allergic rhinitis, in her late teens. Later, she discovered that Tucker’s helped with the symptoms and thereafter never travelled without it (it contained a small amount of cocaine and was vaporised in the nose). It stands for the omnipresence of asthma through her life and her attempts to alleviate its effects in sapping her physical and intellectual energies. It also raises the frequently addictive or otherwise damaging qualities of Victorian medical and quasi-medical treatments, including in her young womanhood being dosed into addiction by treatments given her for asthma by her friend Havelock Ellis, at that point training to be a doctor. She weaned herself off his ministrations, but whether Tucker remained a presence is not known although a point comes when it is no longer mentioned in letters.

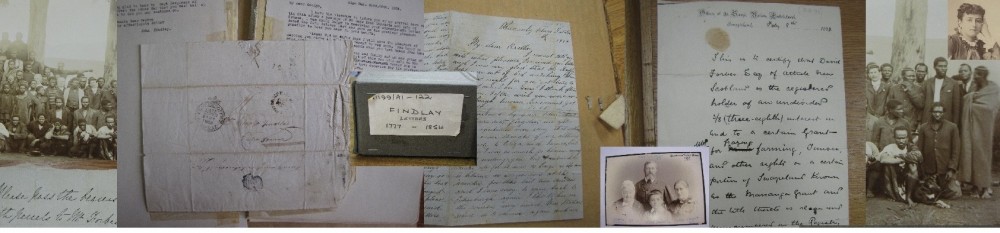

The cloth wrapper in which the manuscript of ‘The Story of an African Farm’ was sent to Britain: Publication of this novel was an extraordinary event, not only in the development of English in Africa, but also of New Woman writing. It also made Olive Schreiner one of the world’s most famous women. Incredibly resonant in terms of Schreiner’s life and her literary activities, it also has an especial resonance because the smell of the wood-smoke of the firesides at which she wrote and then wrapped her manuscript preparatory to it being dispatched to Britain is still detectable, conjuring up South Africa as nothing else does quite so powerfully.

The meerkats: There are no known photographs of any of Schreiner’s brood of much loved meerkats, but they make their presence felt in many of her letters. Their appearances are sometimes hilariously funny, sometimes tragic, more usually quotidian, but always wrapped around the fabric of her life and affections. They were domesticated and loving, but also remained partly wild and lived much of their lives in the veldt that her Hanover house backed onto. There are letters and other writings that express her thankfulness that she lived in a time in which animals were still part of the world around her, although she foresaw a future time when this would not be so because humankind would have destroyed them. Ibred Sin, Tommy Atkins, ‘Arriet, Emmie, Sancho Panza and the others gave her much joy.

The immortal green: From photographs, Schreiner seemingly took some trouble with her clothes in her young womanhood, while later she had little interest in such things. Her dearly loved nephews and nieces used to tease her about her choice of hats and dresses, which were all about comfort rather than fashion. The ‘immortal green’ was a venerable skirt and jacket which she wore relentlessly even though both unfashionable and battered. The joke ran and ran, and at one point she threatened to dress it up slightly and wear it at a niece’s wedding. There were other favoured items of apparel that are frequently referred to as well. Her favourite hat was a dull affair, deeply unfashionable and like a plain man’s Derby or similar. She was given a Kaross of animal skins by friend’s children and always travelled with it. Before that, there was a cloak she valued and once lost, but successfully engaged the London police to find it! What comes across is that things were important, but these had to be the right things because invested with meaning through the relationships they signifIed.

The future: A Schreiner cabinet would not be complete without letters, and the first choice of a letter is a powerful one of 8 April 1909 written to her dearly loved brother Will. In it, she writes about a debate in the Cape parliament in which erstwhile liberals reneged on their political principles with regards to race matters. She was sitting in the gallery of the parliament building next to Dr Abduraman, leader of a political pressure group, and had watched his face as he looked at them. She comments to Will that fate and the future were looking down on the white politicians concerned, with the strong implication that in that future-to-come they would not be there.

The last chance; Another powerful letter also has to be included in any cabinet of Schreiner objects. This is her letter to the politician Jan Smuts, written on 19 October 1920 in the midst of political upheaval and with Schreiner’s gaze firmly on worsening racial hierarchies and injustices. In it she writes that Smuts, as the then Prime Minister of South Africa, was having his last chance to conduct political life with ethical probity towards the black majority The strong implication of her letter is that in spite of his great gifts he would fall morally and politically short, as he always had from since she first met him back in the 1890s. He did, and if any one single individual can be seen to be responsible for the segregated and later apartheid character of the South African state it has to be Smuts, who from the days of the 1902 Treaty of Vereenigen on at crucial junctures steered things in that direction.

Old, battered and so to say with her back against the wall: This is how Schreiner’s estranged husband described how she looked in the passport photograph she had taken in mid-1920 preparatory to returning to South Africa, where she would die on 10 December that year. She was 65, but in the photograph looks considerably older, battered indeed, due to the onslaught not only of lifelong asthma but also the congenital heart condition she and nearly all of her siblings had inherited from their father. In this photograph, she stares steadfastly at the lens gazing at her; she looks indomitable as well as battered. It is in many ways a sad photograph, a sad sight to see. But it represents something more than this as well. She resolutely stands, staring back at the gaze cast upon her. Here for the duration, making the best of things.

Last updated: 10 March 2016