Olive Schreiner’s Address to the Universal Races Congress, 1911

Please reference as: Liz Stanley (2021) ‘ Olive Schreiner’s Address to the Universal Races Congress, 1911’, www.whiteswritingwhiteness.ed.ac.uk/Traces/SchreinerAddress/ and provide the paragraph number as appropriate if quoting.

1. A Universal Races Congress was held in London in July 1911, with delegates and attendees from many parts of the world (Spiller 1911). Olive Schreiner was a member of its executive general committee and had hoped to attend in person, including because she wanted to meet US sociologist WEB Du Bois, whose work she much admired. Too ill with a heart condition to travel, she arranged to send a written address to be distributed to delegates. This was dispatched with her brother Will Schreiner, who she expected to attend the Congress, although (to her chagrin) in the event he did not.

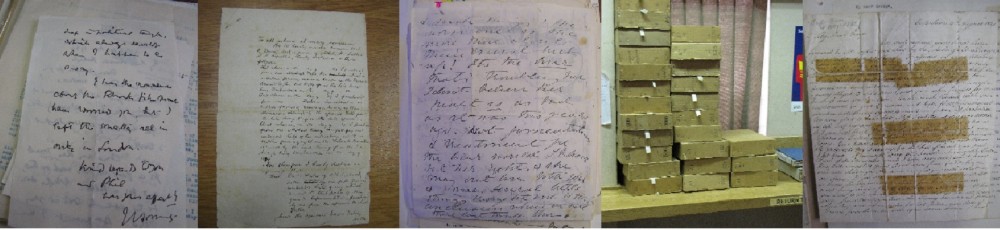

2. Until recently it had been thought that the Address no longer existed. However, thanks to research by Dr Janet Remmington from the University of York, to whom much gratitude is due, it has now surfaced. It is an interesting, indeed an intriguing, addition to the Schreiner corpus in particular regarding race matters and the future of South Africa.

3. Not surprisingly, the Address received coverage in the black press of the day and particularly in South Africa. The version of Schreiner’s Address below, which may (or more likely may not) be an extract from a longer original, was published on 28 October 1911 in the Tsala Ea Becoana (The Friend of the Bechuana) newspaper edited by Solomon Plaatje. Brief comments on it are provided following the Address itself.

4. The Address is:

For us in South Africa the question how ennobling and harmonious relations can be attained between the light and dark races which build up our nations is not one of merely abstract intellectual interest, it is the root problem on the solution of which our whole future national life depends. We have in our population five or six millions of dark races, many of these belonging to the ablest and most highly developed of African races, and we have one million or more of more or less white persons forming for the moment a dominant caste to day. I hope others will express more ably and as fully as I should have liked to have done how entirely the future of our nation depends on our fulfilling our obligation as a dominant caste to day.

If as we break down the social institutions of tribal life, and often very high moral sense of social obligations which has governed our Native races in the past, we turn to him only the lower side of civilisation, if we compel him to graduate in the school of the sweatshop, and worse, and fail to impart to him our higher education and give to him no place in the body politic of our national life, the future of South Africa, not for the black man alone, but yet more for the white, is one which we who are the children and lovers of South Africa cannot look forward to without dark foreboding.

5. Who is Olive Schreiner addressing in this? On a first quick glance, the content seems to express an inclusive ‘us’ and ‘we’ which runs through both paragraphs, as with ‘we in South Africa’. She would have attended from the South African section of the Congress organisational body, so inclusivity about South Africa would be appropriate. But, at points this breaks down and ‘we’ is then actually to be read as the white dominant caste group. So is it addressed to everyone white, or just to the South African white group, or to who or what? There is an identifiable split audience being haddressed; but interestingly, members of the Congress do not appear to be a part of it. Schreiner was in touch with the Congress organiser, was a member of one of its sections, and certainly didn’t expect it to be a Congress involving just white people, as she knew the composition of delegates and attendees. So why might this rather strange sense of audience be so?

6. The explanation could perhaps be that Schreiner’s Address had been written for speaking rather than reading, for she had hoped to attend the Congress before her heart condition worsened and she became incapacitated. The absence of normal punctuation in particular in the last section means that it is not grammatically correct. But read aloud, it works to a crescendo in a kind of breathless way in the second paragraph and is very stirring. However, it is not possible to say whether the published version is how Schreiner actually wrote it, or whether there were issues in deciphering her notoriously difficult handwriting by the Congress organisers or someone else in order to print a version, with differences from what she had actually written as a result. To be heard or to be read? On balance, probably to be read, which makes its mode of address a matter for inquiry.

7. With regard to its content and the message of the Address, South Africa is presented as a special case because of its complex mixtures of different races. Race matters, it proposes, are a root problem there, something fundamental to how its future will turn out. As part of this, there is recognition that there are different African populations, and Schreiner is particularly focused on ‘Natives’ in second paragraph rather than the urban educated elite. She also has interesting things to say about the white caste group in South Africa, with the phrase used to describe this being that it is ‘more or less white’, that is, a polyglot entity with much intermixing with black people. This was the then-dominant caste group when she was writing, ‘for the moment‘; but from sentence construction and phrasing, she is envisaging that it won’t be in the future.

8. Schreiner’s Address and particularly its second paragraph has a strong prophetic aspect, then, and this is worked up in the succession of sub-clauses. Social institutions of ‘tribal life’ have been broken or destroyed and black people are being confined to inferior positions rather than their proper place in the body politic. It ends on a note of warning, that there are consequences in this for white people, not just black people alone, so the prophetic warning seems directed to this caste group specifically. And this is the reason for the foreboding about the future of South Africa that the Address ends with its warning about.

9. Schreiner’s health needs to be factored into considering why the Address takes the form that it does. She was very incapacitated indeed at this point, living in De Aar and with her heart condition worsening in the heat and high altitude. This is what had prevented her from travelling, and it is likely to have meant that she could only write something short and more general, rather than a sustained lengthier piece of work requiring more energy.

10. In addition, Schreiner was involved earlier in writing Closer Union, and this was the time when Woman and Labour was published, and she had also been involved in investigating and countering the ‘so-called Black peril‘. It was written too in the wake of the South Africa Act of Union in 1910 and the immediate passing of racial legislation by the new national state and its repressive action against strikers. This context of immense political retrogression with regard to race matters in South Africa and its politics therefore also has to be taken into account in thinking about the Congress Address’s prophetic tone and culmination in foreboding. And it is the context of course in which Plaatje published it.

11. The Address is a warning without the promise or even a hint of a solution. Schreiner has written something with a fundamental message that is not addressed to the Congress delegates, but to the future that is being warned against and the white caste group that was bringing it into being.

Reference

G. Spiller 1911 Papers on Inter-Racial Problems communicated to the First Universal Races Congress. London: PS King.

Last updated: 11 December 2021